Portimão and Vila Real de Santo António are the last counties analyzed in the fruitful report by Aires Garrido, civil governor of Faro, thus fulfilling the government's determination to visit the entire district and note the economic and social status in which it was found, as well as to work towards the resolution of the main problems.

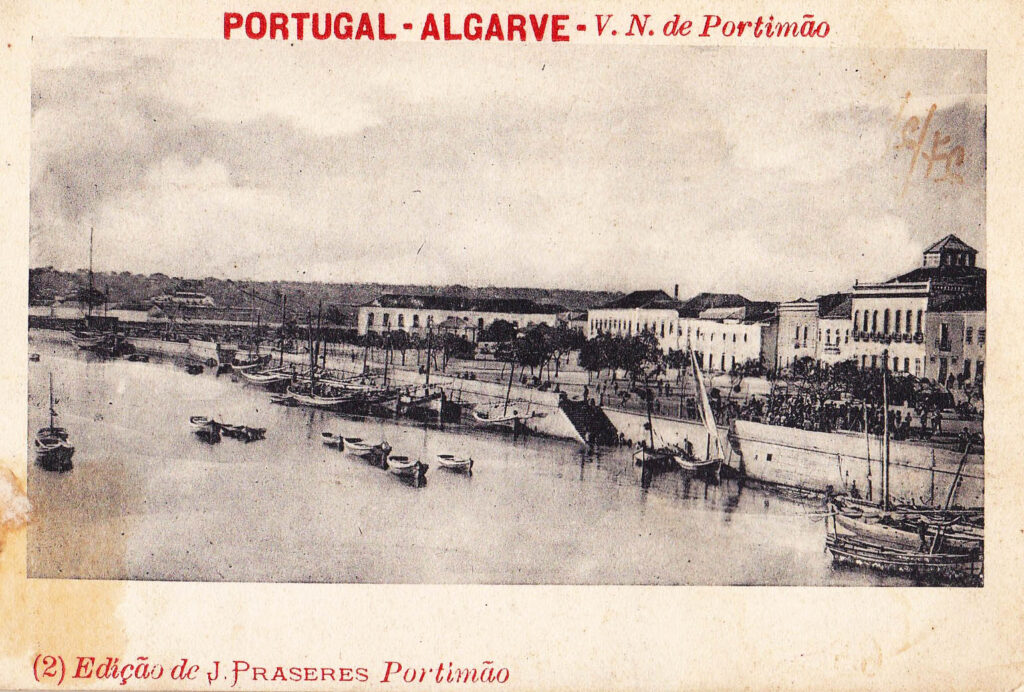

about then Vila Nova de Portimao, who only ascended to the category of city in 1924, by the hand of the prodigal son Manuel Teixeira Gomes, wrote: «this villa has 1:160 houses, 346 more than in 1839. As the most commercial land in the Algarve, it has progressed a lot in this way in population increase as in material improvements; it is well policed, its streets are well paved, some of which are made up of buildings almost all of recent construction and elegant prospectus, what's more, and its location on the bay of the river of the same name, which makes the best of it next to it. and the most frequented port on the coast of the east district, it gives the villa a pleasant and cheerful appearance».

Portimão stood out in the Algarve panorama for its people, location, material improvements, commerce and urban growth. Despite suffering a huge constraint, “it is a pity that there is no drinking water in it”, the lack of the precious liquid did not prevent the village from growing and developing.

The water was transported "some distance in tankers, and in inconvenient conditions", from the cover of Gramacho, we added, upriver, to the gates of Silves, until there.

The governor recognized that it was not impossible "to bring water from one of the sources of the nearest mountains to it", however, it was very expensive. However, he believed that the work would not take long, "taking into account the spirit of progress that I noticed among its principal inhabitants".

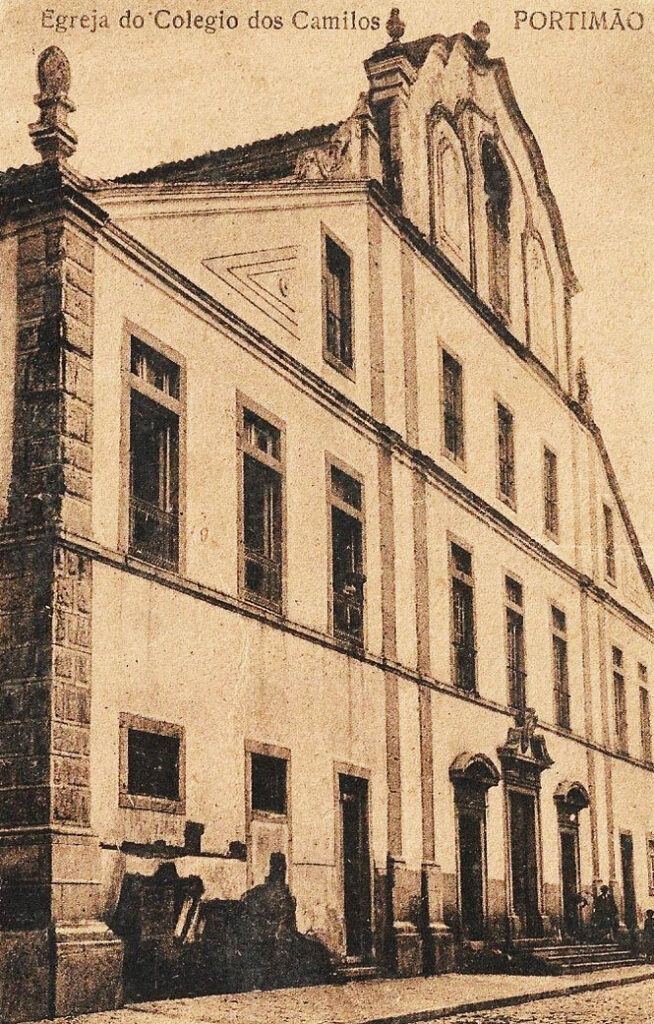

The public offices were all concentrated "in a part of the building that was formerly the Jesuit College and later the convent of Camillos, granted to the chamber for that purpose, with the hospital of S. Francisco and the mercy in the other part."

However, if the building was appropriate, «the papers, however, were poorly arranged, there being some on the floor, for lack of shelves, for whose purchase I gave the most definite orders, and took note to check if they were fulfilled». There was also unbound legislation, as well as "some other faults that could be easily repaired", attributed to the inexperience of the new clerk, who had nevertheless shown "he was zealous and willing to get it right".

With a considerable income, the City Council allocated it to "works on sidewalks, repair of paths, public fountains and wells, bridges and the like", as well as "for roads of the third order".

As for debt collection, it was deficient, a neglect practically transversal to the region. The budgets were approved until 1854-55, while the rest awaited consideration. At the level of the parish councils, it faced some delays, which ranged between 2 and 4 years, having taken care of it.

Another difficulty, still in the process of being resolved, was linked to the cemetery: «as the public cemetery was very poorly located, and the public cemetery was deficient, the town hall built another one in good exposure and situation, which was blessed in the close to the end of the year, and it is serving, lacking only a few touches, for the expenditure of which the competent amount has been voted in the budget».

Alvor also had problems with the necropolis: “in addition to not having sufficient capacity, it is poorly located, next to the parish church and very close to the village”, and the governor proposed the construction of a new one. In a better situation was the one in Mexilhoeira Grande.

In the county, there were three Misericórdias (Portimão, Alvor and Mexilhoeira Grande), as well as a legacy in the village, called S. Nicolau, whose income was administered by the Third Order of S. Francisco and applied to helping the sick in their own homes .

The Misericórdia de Portimão had a hospital, in good condition, with a capacity for 24 patients. There was also a mutual aid association, with 129 "artist" members, as well as a maritime commitment.

Of the 9 inhabitants of the municipality (383 Census), 1864 (93%) survived from begging, while 1 (51%) did not beg but lived on public charity. In terms of schooling, there were 0,5 male public schools, attended by 3 kids and 101 private ones: 4 for boys (2 kids) and 55 for girls (2), out of a total of 54 boys and 749 girls of school age. In this sequence, only 794% of boys and 20% of girls studied. That's how Vila Nova de Portimão was in the childhood of Manuel Teixeira Gomes, at the time, aged 6 years.

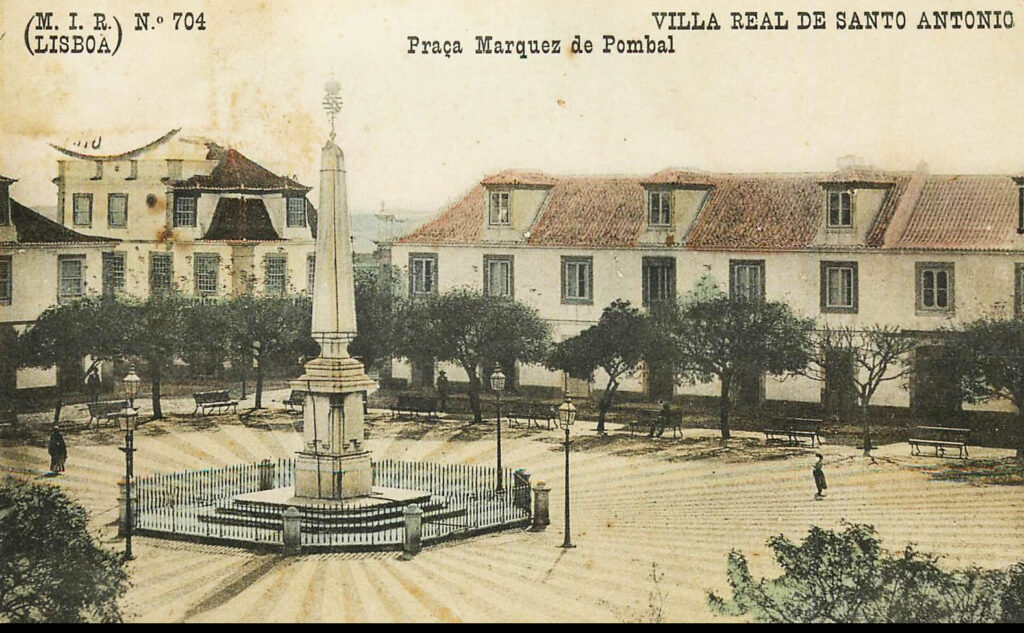

At the eastern end of the region, Vila Real de Santo António it was the last municipality to receive the judgment of Aires Garrido. About him he stated: «this council is one of the smallest in area and population; it is made up of two parishes, both with little more than 1:000 dwellings: on those that it had in 1830 it has today the town plus 470».

An increase in population that forced the «construction of new houses, and the opening of more streets, in which the plan of the primitive construction has been followed, thus turning the villa into a very healthy, accepted and pleasant land».

Vila Real had seduced the governor. Despite not having an abundance of "personnel for municipal posts, because the population is almost entirely maritime", it was "less poorly managed, and it is a pity that its resources are so scarce to take care of the material improvements that it so badly needs" .

Even so, «almost all the streets are paved, and the public offices, since they are not as well housed as they would like, they are very poorly, as well as the primary school, because the houses of the town hall and others that the latter is rented to the offices that do not fit in those, are decent and have the required capacity».

The municipal revenue was reduced and resulted from contributions, the own income being very small, «however, this amount could have been much higher if the council had used the extensive sands that lie south of the villa up to the coast to plant pine trees. from the ocean, which, in addition to the income it could produce, sheltered the villa, preventing the damage caused by the invasion of the sands», warned the governor.

A measure that the city council postponed, considering it necessary to raise taxes to "pay for the expenses of sowing, guarding and preserving the pine trees, and the fear that they will be destroyed by ignorant and evil peoples".

Discouragement that the governor tried to solve, proposing the execution of regulations, as well as their sowing in installments, in addition to instructing the administrator "to make the public opinion favorably disposed towards this measure and to convince itself of its usefulness". In short, it was necessary to publicize and convince the Vila Realenians of its importance.

In fact, it would be of “recognized advantage for the municipality, and for this entire district, where the shortage of wood for fuel is generally felt, and the absolute lack of wood for construction” and, therefore, an important source of municipal revenue. . In April 1867, the measurement of the land and the preparation of the budget for this purpose were underway.

Another work that was required «of the highest necessity in this municipality is the construction of a dog on the Guadiana in front of the villa, to protect it from the invasion of water», is that these «are successively digging the sand of the beach, and already threaten the buildings in some points». His absence put the town itself at risk, and Aires Garrido provided the budget and project for its execution.

In administrative terms, the Chamber's budgets were approved until 1857-58, with the remainder being analyzed. In the «notary offices of the chamber and of the administration of the council, I did not find any notable irregularities, and I took the measures that I believe were necessary to correct some small omissions or defects». At the level of parish councils, some delays were detected.

Vila Real de Santo António knew some dynamic in those years, «the movement of the port, where many ships concur to transport the ore extracted from the mines of São Domingos, has contributed a lot to lift Villa Real from the despondency in which it lay due to the decay of fisheries ».

However, the farsighted governor did not fail to recognize that «it is nevertheless necessary to take this opportunity to undertake the indicated improvements there, since it may one day fail, and leave the village in circumstances even more critical than those in which it was before the beginning. operation of said mine'. After all, then as today, communities should not rely solely on economic activity.

With regard to public health, “both the cemetery of the town and that of Cacella are well located and decent”.

In the municipality, with 5 059 inhabitants (1864 Census), there was no Misericórdia, or hospital, or mutual aid associations, with the exception of a Maritime Commitment. It had 647 members and was one of the largest in the district.

According to the data presented, 15 people survived from begging, while 3 lived on public charity, that is, 0,3% of the population was extremely poor. Values still reduced when compared to other municipalities.

In education, 3 male schools, 2 public and 1 private, taught the first letters to 60 and 30 boys respectively, out of a total of 863 (10%). The 665 school-age girls did not attend any educational establishment.

An administrative reform that never advanced

Although Portimão stood out compared to Vila Real de Santo António, the latter still constituted, in what we can classify, as an intermediate example in terms of administration, in the disconcerting journey that we carried out in recent weeks.

Vila Real was the exception in the context of the peripheries, it should be remembered that Alcoutim, Castro Marim, Aljezur and Vila do Bispo were councils where the governor detected more problems and shortages of human and material resources, such as in Monchique.

It even proposed the merger of Aljezur with Monchique, Vila do Bispo with Lagos, and Castro Marim with Vila Real de Santo António. For Alcoutim, the distance to these last towns had weighed on him and, despite the indictment, he did not materialize it.

From the analysis of the Reports made in all the districts, based on direct observations of the governors, the government proceeded to draft the Civil Administration Act of June 26, 1867, an attempt to reform the administrative code, which would become known by de Martens Ferraz.

According to Jorge Manuel Dias Fernandes, in "The unpopular administrative reform of 1867", which we have already mentioned, that, among other aspects, foresaw the reduction of the number of districts from 17 to 11, while the councils, of the approximately 350 existing, remained 178 and parish boards from just over 4 grew to about 000.

The government thus sought to reduce expenditure on administration, trying to overcome the crisis that was going on, with high deficits in public accounts.

The final map of the reform was published on December 10, 1867 and, according to Daniel Alves, Nuno Lima and Pedro Urbano, in «State and society in conflict: the Code of Mártens Ferrão of 1867. An ephemeral administrative reform», in the Algarve os 15 existing councils were aggregated into 8 (Aljezur, Vila do Bispo and Lagos; Monchique and Portimão; Lagoa; Silves and Albufeira; Loulé; Faro and Olhão; Tavira; Vila Real, Castro Marim and Alcoutim).

Civil parishes now number 36, out of 65 ecclesiastical. The district also changed its designation of Faro, to Algarve. It is not by chance that the municipality of Lagoa was maintained, regarded as exemplary by Garrido, even with other parishes.

However, together with the increase in taxes, a huge popular and political discontent was generated in Portugal, which culminated in the protests of January 1, 1868 – the Janeirinha.

As a result, there was the fall of the government and with it of the civil governors. Aires Garrido (1805-1874) left Faro on 18/1/1868, coming in the following August to occupy the same position in the Guard.

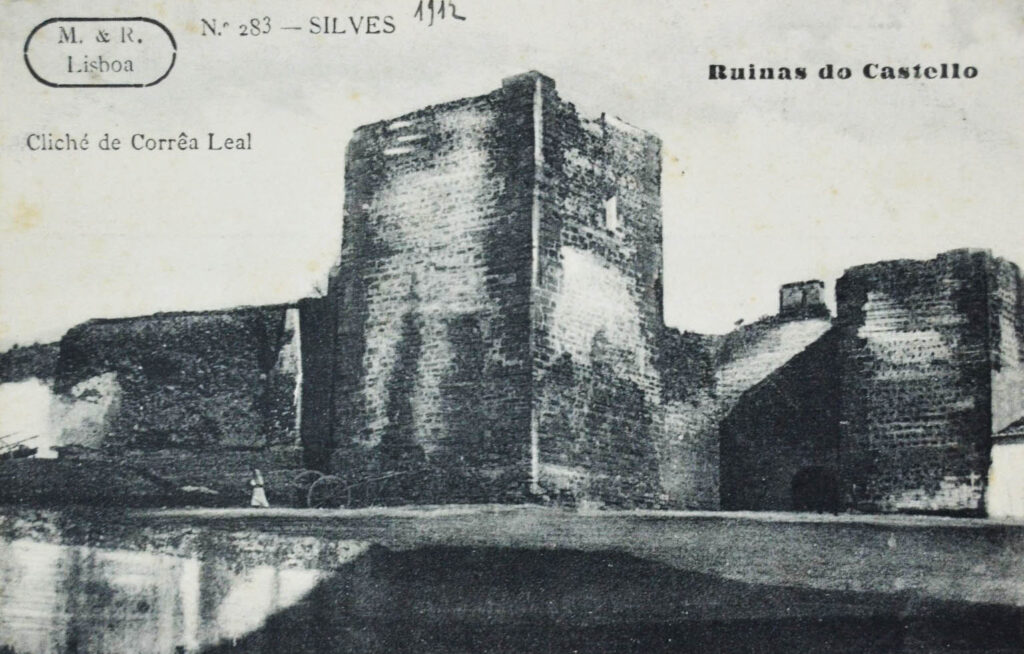

If his passage through the region lasted 20 months, the Report he left us shows us a man who was zealous in fulfilling his obligations, interested in the means of communication and in public health, the purposes of the time, but also ahead of his While in Lagos he defended the demolition of the walls, in Silves he promised to oversee the works in the Cathedral, ensuring the maintenance of the Gothic form, in order, in Vila Real, to congratulate the authorities for accepting the enlightenment of the city's design in urban growth.

Here, too, he stressed the importance of diversifying economic activity, a problem as current as it was then. His concern with teaching was constant, as well as by the most unprotected, accusing the authorities and institutions of doing little to minimize those “wounds” in the Algarve in the XNUMXs. Entities, with very few exceptions, as we have seen, occupied by selfish and backward elites, more concerned with “dinners and refreshments”, to use their words, than with promoting the common good.

The Report, organized by councils, gives us precious information, unlike magistrates from other districts, who organized them by subject/thematic, losing many particulars.

The conclusions that we can draw from it are varied and vast, but it is important to say that the reality described for the Algarve was not dissimilar to the rest of the country.

It is not by chance that, in Portugal today, only 52% of its inhabitants have completed secondary and/or higher education, while the European Union average is 78%. Investment in qualified human capital has rarely been a national priority, and despite the enormous evolution in recent decades, we are still in the tail, with extremely high costs for the country.

The descriptions we have followed over the past few weeks should encourage us to reflect. It should be noted that, in terms of administration, of the 15 existing councils, only three stood out, Lagoa, Tavira and Portimão, five were really bad (Alcoutim, Castro Marim, Aljezur, Monchique and Vila do Bispo), whereas in Lagos the prevailing corruption. The remaining six municipalities fell in the middle (Albufeira, Faro, Loulé, Silves, Olhão and Vila Real de Santo António).

If the Algarve has barely survived 150 years ago, it is certain that there are many remnants and ways of being, in many municipalities, which have reached our days, with alienated and apathetic societies, mediocre politicians, indebted councils and wasteful institutions.

When we are going through yet another crisis, with taxes reaching indecent levels, it is worth remembering that administratively, at the council level, the country is still a reflection of the administrative reform of 1836.

Almost 200 years later, when there is no lack of excellent terrestrial and digital communication channels, and mayors move from one municipality to another, regardless of any affinity with that territory, it is grotesque for society and the State to maintain an anachronistic administrative structure, focused on the past, rather than adapting it to the present and the future.

But these are other issues, other themes. For now, in the Algarve of 1868, the Algarvians breathed with relief, the inopportune and undesirable governor disappeared to the delight of the rude and poor people and the petty and backward elites, after all everything would remain as before, at least for a few more years...

Author Aurélio Nuno Cabrita is an environmental engineer and researcher of local and regional history, as well as a regular collaborator of the Sul Informação.

Note: In the transcripts, the spelling of the time was maintained. The images used are merely illustrative and correspond to illustrated postcards from the last decade of the XNUMXth century and/or early XNUMXth century.

Read also the previous five parts of this article:

The Algarve in 1867 or a devastating portrait of the Algarve and the region – I

The Algarve in 1867 or a devastating portrait of the Algarve and the region – Castro Marim and Faro

The Algarve in 1867 or a devastating portrait of the Algarve and the region – Lagoa e Lagos

Comments