On April 25, 1974, José Vitorino was 19 years old and a student at the Lisbon Commercial Institute (ICL).

50 years ago, few people had cameras, cell phones were still a thing of science fiction and there were even few telephones or even radio sets. Only the wealthiest had television.

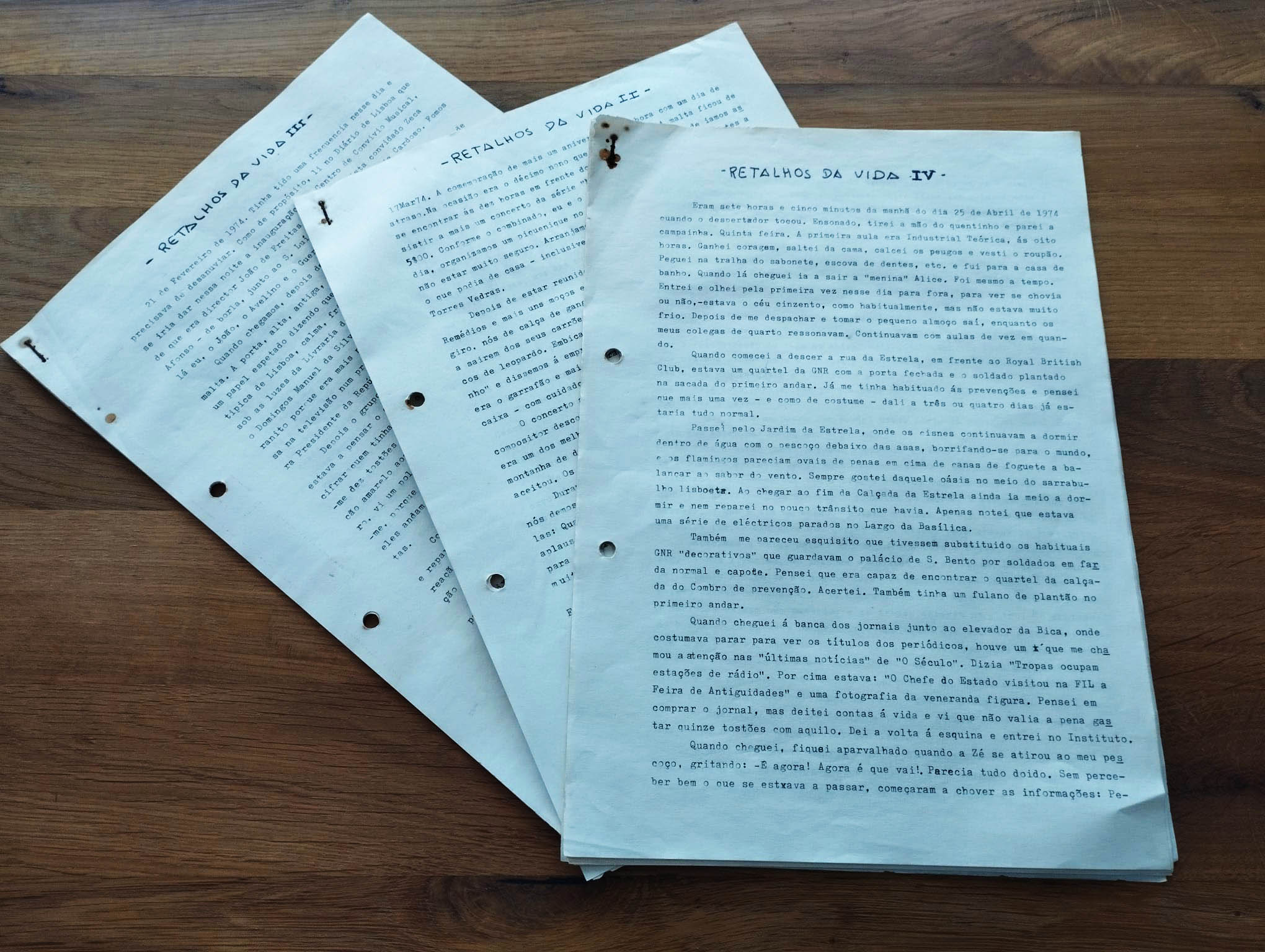

But José Vitorino, an Algarve native from Portimão, recorded, in writing, on well-organized pages typed on a typewriter, his memories of those days of fright and wonder, which he lived with enthusiasm and fervor.

Here is a chapter from his «Retalhos da Vida», sharing in the first person what that «initial day, whole and clean» was like.

It was seven and five minutes in the morning on April 25, 1974 when the alarm clock rang. Drowsy, I took my hand away from the warm and stopped the ringing. Thursday. The first class was Industrial Theoretical, at eight o'clock.

I gained courage, jumped out of bed, put on my socks and put on my robe. I picked up the soap, toothbrush, etc. and I went to the bathroom. When I got there, “girl” Alice was coming out. It was just in time. I went in and looked outside for the first time that day, to see if it was raining or not – the sky was gray, as usual, but it wasn't very cold. After checking in and having breakfast, I left while my roommates snored. They continued with classes from time to time.

When I started walking down Rua da Estrela, in front of the Royal British Club, there was a GNR barracks with the door closed and the soldier standing on the first floor balcony. I had already gotten used to the precautions and I thought that, once again – and as usual – in three or four days everything would be back to normal.

I passed by Jardim da Estrela, where the swans continued to sleep in the water with their necks under their wings, spraying themselves out into the world, and the flamingos looked like ovals of feathers on top of rocket canes swaying in the wind. I always liked that oasis in the middle of Lisbon's sarrabulho.

When I reached the end of Calçada da Estrela, I was still half asleep and didn't even notice how little traffic there was. I just noticed that there were a series of trams stopped in Largo da Basílica.

It also seemed strange to me that they had replaced the usual “decorative” GNR who guarded the S. Bento palace with soldiers in normal uniforms and capes. I thought I was able to find the headquarters on the Combro sidewalk for prevention. I got it right. There was also a guy on duty on the first floor.

When I arrived at the newspaper stand next to the Bica elevator, where I used to stop to see the titles of the periodicals, there was one that caught my attention in the “latest news” of “O Século”. It said: “Troops occupy radio stations.” Above it was: “The Head of State visited the Antiques Fair at FIL” and a photograph of the venerable figure. I thought about buying the newspaper, but I looked into it and realized that it wasn't worth spending fifteen pennies on it. I went around the corner and entered the Institute.

When I arrived, I was shocked when Zé threw herself on my neck, shouting: – It's now! Now go!

It all seemed crazy. Without fully understanding what was happening, information began to pour in: through Graça, I learned that there was a movement of troops near the Sintra line; by Ana, who had tanks on the riverbank; another said that Baixa was surrounded by troops.

A radio was discovered I don't know where. You only heard music from “contra” – Zeca Afonso, Adriano Correia de Oliveira, JJLetria and the like. I ran to buy “O Século”, and screw the budget. After all, the newspaper didn't contain anything more than what I had already read.

The ICL was in an uproar, with a mix of fear and joy. Groups of conversations were formed and broken up, we went to the doors to get more information from those who arrived, we took a quick stroll to the closest corners to see if we noticed anything strange. The group was almost formed to go on an expedition to see what was going on, when the Industrial Theoretical professor arrived. His mouth dropped open when he saw how relaxed the guy was when he walked in the door, waited for us to sit down and started explaining the material. We were so upset that we didn't even react and stayed in class.

Half an hour later, he stops in the middle of what he was saying, puts his fingers together and says very calmly:

– What’s wrong with you? I'm tired of explaining this, but I notice that you're not here. What's?

All my people started explaining what was happening at the same time and he didn't understand anything. I showed him the newspaper clipping. Then he, very surprised, remembered that he had called Emissora Nacional as usual and was unable to catch the morning program. And even a soldier – it's true, what was a soldier doing there? – had told him to go to another street, and he had to run halfway across town to get to the Institute.

We finished class, we all left and went to Baixa. In Camões and Rossio, no traffic, just people walking very quickly. At the end of Garret Street, we turned right and came face to face with the first troops. Rua da Conceição was busy and no one passed by.

The people, fearful and curious, were on one sidewalk, and the troops were on the other. At the intersection of Rua do Ouro, there were the first Chaimites I saw. But what scared me were two soldiers lying next to the curb, with two tripod machine guns pointed at Rossio.

The first questions were heard. -Which side are you on? – asked a civilian, but the soldier did not respond.

A short guy, wearing a coat, who was next to me, said: – I found a boy from my hometown – that one there – and he told me that they came from Santarém to put an end to this.

– What is this? asked several. He shrugged his shoulders and replied that it seemed like they were against the Government. People were already reaching that conclusion, turning it into certainty.

Someone remembered that they were capable of being hungry. Out of nowhere, a huge plastic bag full of sandwiches appeared. They began to offer tobacco and a momentary fraternization ensued, a prelude to the madness that would happen in this regard.

A soldier was eating a ham sandwich, while, with his mouth full, he said that he had been in the firehouse since three in the morning and had not yet eaten anything.

Visibly nervous, an officer who had been talking to a group of bank employees (among whom was my Industrial teacher), ordered people to stay away. Nobody really cared. When he gave the order to prepare the weapons, there was even a more nervous soldier who dropped something metallic (I believe it was the loader). This dry noise acted like a whip.

The order was given to pull the breech back and someone, unnerved by the noise, began to run away. It was the trigger. Legs so I want you. I never thought I would be able to climb the slope of Rua da Conceição so quickly. I was walking with my head down, almost crouched, and, looking at the sidewalk next to me, I saw two troops cowering in a doorway, with their weapons pointed at the area we were coming from. Then I got wings. The mob ran like lightning. When I realized, I was, with part of the group, in Chiado.

It was about half past ten. We decided to methodically explore the situation. We went to the Graça viewpoint. From there, we saw the Tagus, and, in the middle of it, a war boat, smoking, with batteries pointed in the air. When we went down to Baixa again, there was an oppressive silence, as if the city was holding its breath. From time to time, small bursts could be heard.

I separated from the crowd. I went to Rua da Conceição again. There were no troops there anymore, it was now possible to pass. Curiosity was stronger than fear. I went to Terreiro do Paço. Next to the Ministry of Defense, there was a passenger truck, from the troops, with people inside. Nearby, two tanks and armored vehicles could be seen. Groups of soldiers came and went. A black Citroen DS arrived for a short time and left like an arrow.

In the Tagus, right in front, the frigate was still there. Later, he learned that his commander had given the order to fire a warning shot, using dry powder. The gunners refused to obey the order. At that same moment, in a nearby alley, two tanks and several troops were opposite each other. Some for the Government, others against. If that shot had been fired, the civil war would have started there.

Then, a police officer arrived next to me. It was a “shock”. Distracted by what was going on, I heard him say: – I'm sorry, but are you able to get out of there? It's just that it's blocking traffic. Mechanically, I turned around and left. I heard a “Thank you!” in the distance.

It feels like I got screwed over and suddenly I had the feeling that we had won. It was a riot police officer who created my disgust towards the Government. It was someone else who told me that this Government had finally fallen.

I was walking next to a construction site when I started to see people running. I started walking faster. Along one of the intersections, I saw, in the background, troops passing through a lot of people. Behind me, I hear shouting “-The Navy is coming”. It was the biggest scare I got that day. If the Navy was against it and the other troops were up there, I was in the middle of the war.

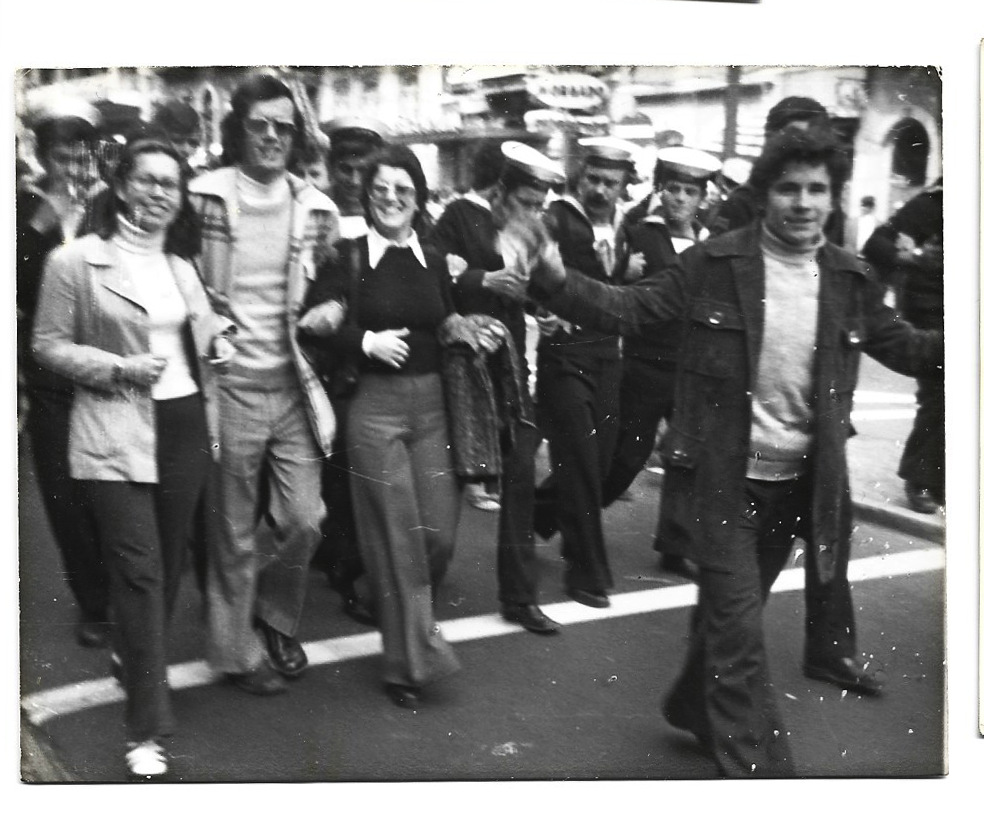

When I arrived, breathless, at Rossio, I was amazed. It looked like I had fallen in the middle of a fair. “Long live freedom” and “Long live the MFA” were heard. I saw tears in the eyes of an old man, who had a twenty-year-old smile. Chaimites loaded with people full of red carnations, slowly passed through a sea of people. When I realized, I was next to João. Nearby, a jeep passed by with a square of red cardboard placed in the corner of the windshield (it was the contra's badge).

A police car was across, blocking the ascent to Rua Nova do Almada. The party stopped. A small drama unfolds: the jeep's tires squeal, and it stops with a jerk. A soldier stands up and says to two police officers who were dumbfounded looking at it: – Get this shit out of my way! Without a word, the two quickly get into the car and disappear.

The column starts moving and the party continues. I look at the clock. Half past noon. João says that hunger is already starting to tickle. Let's go home. Along the way, as we move away from the center of events, the city seems to be returning to normal, more people, more cars. Every now and then, you notice a group of soldiers, a GNR barracks completely closed, an armored vehicle on a corner. But life went on.

At D. Virgínia's house, people were agitated, a thousand and one hypotheses were raised. The radio was open and, when you heard a military march by John Philip Sousa (of Portuguese descent) whose name was, unless I'm mistaken, “Above the waves”, there was silence, because afterwards came a statement from the Armed Forces Movement .

After lunch I went to my cousin Elias' brother's house, where the whole family was gathered. Carlos had a very good portable radio and had tuned it to the band in which the GNR spoke. At that time, he was in the army, but they had sent him home.

In Cova da Moura, which was one of the Lisbon HQs and where he was stationed, it was confusion. Nobody gave orders and everyone gave them. There were some very quiet ones and even a big Navy officer who had arrived there without knowing anything. When he was made aware of what was going on, he asked if he wasn't being arrested, to which a corporal said: -Maybe he is! Look, stay here and we'll see. And he sat there very well, waiting. From time to time, he would even ask if they knew anything about his situation.

A driver for a general had also arrived there and was very worried because the “Senhor General” couldn't go to work without his car. We were interrupted by the radio: -“Attention Mike Rómio, I’m listening! Mike Rómio, I listen. We cannot progress. The situation here is very confusing. The civilians won't let us move. Down there I already had problems with them. They threw stones and made movement difficult. As we haven't moved, they think we are now friendly troops. I don't know what to do. I listen.”

There was silence only broken by static. Then a voice sounded and said: “- Understood and finished”. These were some GNR soldiers who were in Largo do Camões, and the conversation clearly revealed their state of mind.

Meanwhile, we had some drinks and appetizers and the afternoon passed. From time to time we could hear some more radio communications, one of which was from a Guard platoon that hours before had been ordered to go to Baixa and was still in Praça do Chile. From time to time, the command of the Carmo Barracks asked if they had arrived yet. They didn't go beyond where they were.

By five o'clock, I was ready to go and see what was going on. I told my cousin I was going home so he could rest.

I took off at a run and, not even on purpose, I immediately ran into João and Guerra who were coming from Baixa. According to them, the situation was under control, but there was still unrest in Carmo.

I went there straight away. In Camões, there were sad people from the GNR watching who was passing by. I went up to Carmo and, as I walked, I met more and more people. When I arrived, I found a sea of people. It was a traditionally Portuguese festival. People perched on top of trees at the fountain in the middle of the square and not even the tram stop, which had a tin roof, could escape. It even collapsed under the weight of the staff.

All my people were celebrating, full of carnations, joy, soldiers, armored vehicles, confusion. Soldiers were already seen full of bottles.

One had four: one in his blouse pockets, two in his pants pockets and one in his hands. Despite everything, he still managed to handle a G-3, which served as a reminder that this was no party. The barracks wall had bullet holes and several windows were broken. Every time someone peeked out from inside, there was a terrible booing.

A captain (who I later learned was called Salgueiro Maia) on top of a chaimite urged the people to get out of there, because everything had already been resolved. But I found the soldiers too tense looking into the air. Following their gaze, I saw others placed on the roofs of the neighboring buildings. They were afraid that some helicopter would appear.

A black Peugeot 304 arrived. Inside came General António de Spínola. Shouts and cheers. He can barely get out of the car and enter the Barracks. (He later learned that Marcelo Caetano didn't want power to fall to the street, so he sent for him to give him his testimony).

I walked around the surroundings, seeing the troops and meeting people I knew from the ICL, all excited, so that, when I returned to Largo, I saw a Chaimite leaving with a jeep in front, making way.

When it became known that Marcelo was inside, it was the end of the world: – people punching Chaimite's armor, huge boos, people went crazy. The fall of the regime was complete.

I walked and, before arriving at the building of the newspaper “A República”, I watched the “hunt for the pide”: many people running away shouting “- Agarra que é pide”, only stopping at Largo da Misericórdia, when the troops saved the pides of being caught and of being beaten. But even so, people were mad. They took revenge in the car in which they came. They turned the car over and broke it apart. It was a brand new Toyota.

In “A República” there was an individual very solemnly placing green and red lamps imitating the national flag beneath the billboard. The issue of the newspaper that came out that day had a banner saying: “- THIS NEWSPAPER WAS NOT VIEWED BY ANY CENSORSHIP COMMITTEE”. All my people bought newspapers. It was crazy.

I decided to go to dinner. When I turned towards Largo do Camões, a spontaneous demonstration of the many that formed in the midst of popular enthusiasm was coming up the street. I even thought about getting into it when they headed towards Chiado, but it was already late for dinner and it started to drizzle.

When I looked at them again, they were turning onto Rua António Maria Cardoso. I'm glad I didn't go with them, because the only deaths that day resulted from this demonstration: as they passed under the PIDE/DGS windows, they fired several shots. Two young people fell forever, and three more were injured. Once again, they showed what they were.

At home, where everyone was gathered in the living room discussing what was going on, we stayed until two in the morning to watch this National Salvation Board thing. There were two things that impressed me in this television broadcast: the arrival of members of the Junta, as they were going up the ramp that gave access to the studios, and the look on Galvão de Melo's face, like a guy who would rather break than cheer.

The next day, the party continued. Of course there were no classes. The Institute was tingling. A statement came out against Spínola, calling him a Nazi and talking about his intervention in the Spanish War in the Blue Division.

In the afternoon, I went to see the DGS headquarters (the initials stand for General Directorate of Security and not General Directorate of Health, despite take care of health to staff). It was still isolated and, along all the streets that gave access to it, there were troops, jeeps, chaimites and even a tank, which seemed to be guarding the building.

Next to S. Carlos, there was a car with several bullet holes. It was from a Pide who had tried to escape. A few days later, on May 1st, I took a photo next to that car.

Meanwhile, in Largo do Camões, people gathered and were pushed by troops who wanted to block the access to António Maria Cardoso. I was on a bench in the garden with Ana, Graça, Corado, in short, the ICL group. The crowd was nervous and excited. It felt like we were standing on a powder keg.

Suddenly, coming from Largo do Calhariz, two “níveas” from the PSP – Shock Police arrived. It was to set fire to the fuse. The population reacted like crazy. I really don't know who made the mistake of sending those guys, who represented the most hateful things that existed in the fascist regime, there, when people were drunk with freedom, and what they had endured was still fresh in their memory. The fire reached the gunpowder and I saw a hand come out of the window of one of the “níveas” and fire two shots into the air. It was the end. The troops thought they were shooting at her and fired back.

The people flew off the bench to take shelter. I almost passed over a parked car, I dodged an old woman who was knocked down by someone next to me. Half crouched and running next to the wall, I turned towards one of the streets of Bairro Alto, tried to break through and get onto a staircase, but the one I found with the door open was already full to the top.

I continued running and, already close to “O Século”, I stopped with my heart pounding. I walked around and found the group. Graça and Ana had ended up in a restaurant. Graça only stopped in the kitchen. Ana stayed in the room, but there was a guy who came flying in, breaking the glass in the door and then all my people, in fright, threw themselves to the floor. From this confusion, I had two images recorded in my mind: the “shock” firing and a soldier sitting on the sidewalk with the G-3 leaning against the wall firing into the air. Days later, I found the same soldier “patrolling” Garret Street, hugging a gun on one side and a girl on the other.

The following Saturday, I fell into the middle of the “Peralta Case”. Pedro Peralta was a Cuban captain who was shot in the leg and captured in Guinea. He was at the Estrela Main Military Hospital at the time. A number of far-left organizations called for his release.

When I left the house, I was surprised to see so many people inside Jardim da Estrela. Even an old man who used to sell newspapers, which he hung on the bars of the Garden's railing, was this time right inside, instead of, as usual, outside the Garden. There were a lot of loose stones, which was always a sign that there was something in the area. A guy passed by me carrying (poorly) disguised an iron bar wrapped in newspaper.

Upon arriving at Largo, there was the traditional demonstration, gathering and soldiers, some of them mixed together and supporting the demonstration for the Cuban's liberation. I even saw him peeking through a window at the hospital. Traffic was interrupted, the tram lines had been blocked.

Suddenly, coming from I don't know where, a tank comes out at great speed and spins in front of the Basilica. The driver of that must have been crazy. The crowd got excited, and, coming from Avenida Infante Santo, I saw the “blue paint car” arrive, having been greeted by a shower of stones. One of the protesters managed to climb onto the bodywork and break the pipes that connected to the water hoses. The car was out of action. In the aftermath, the Internationalist Communist League (LCI), one of the groups that supported the demonstration, withdrew amid major discussions.

The following day, a Sunday, the television broadcast live a Grand Prix in Formula 1. During breaks, I made a few trips to Estrela to take stock of the situation. There were still some protesters lying in sleeping bags or sitting on the ground, with posters stuck in the lines of the yellow, paralyzing traffic.

After finishing the broadcast (Niki Lauda won, in Ferrari), I went back there. When I arrived at the intersection of Ferreira Borges and Saraiva de Carvalho, there were a bunch of people looking down at Estrela. I saw some confusion and commotion down there, and decided to go and see what it was. When I got there, there was a GNR squadron on horseback (the capicuas – crossbow, saddle, crossbow) in Largo. They were wearing gray helmets and coats, being booed and insulted a lot.

Eventually, they start to form in line and try to push people around. Stones begin to fly and, at the same moment, they advance. It was scary. Only those who have seen something like that know how to value it. It was a cavalry charge. A compact line of horses trotting up the street, moving everything out of the way. They threw their hands to swords and then I went through the first door I found open. I found a lady there sitting on the stairs, almost crying, because she had been caught in the noise and almost got tangled up in that huge, gray, blue and brown wave.

I went to take a look and saw them up there, while people were running against the walls and around the wheels of cars because of the horses. I took shelter for a while longer and then went down to avoid them. I managed to infiltrate the current and get out of the noise.

Comments