By ordinance of August 1, 1866, the civil governors were summoned to annually visit the districts they headed, a practice that came from the law, “because this is the most adequate means to know the true needs of the districts, and to provide for themselves about them in a convenient way'.

In addition to supervising the different branches of administration, they were charged with drawing up a summary to present "so that, in view of these reports, the government may attend to the needs of the public administration."

Tempers in Portugal had finally calmed down, the turmoil arising from the French Invasions (1807-1811), the Liberal Fights (civil war between 1832-1834) and the Patuleia (1846-1847) were now over.

In 1851, a final military coup gave way to Regeneration, a period marked by the effort to modernize the country in relation to Europe, which had already taken off in terms of development. Thus began the construction of macadamized roads and railways all over the place.

However, a few years later, in the mid-1860s, finances and public debt were in a shambles, or in other words, the country was in crisis.

The situation, according to Jorge Dias Fernandes, in the «Unpopular Administrative Reform of 1867», resulted from the unfavorable international situation, which prevented recourse to foreign loans, to which was added the fall in income from emigrants in Brazil and, as if not all that had to be added to this were some wrong government policies.

Dear reader, we are in the 1860s, any resemblance to the present time is pure coincidence.

But today, as then, governments have sought to cut spending, however, without the intended result; the deficit grew and was extremely high in 1867.

In this context, several reforms were elaborated, among them the one of the local administration, which foresees the modification in the structure of the local power and the division of the territory, as well as tax alterations. Modifications that immediately presupposed the extinction of councils, a reality clearly evident in the report written by the civil governor of Faro, given to the print, along with all other districts, in 1868.

In fact, it is today a fundamental document for us to understand the country and the Algarve at that time. A region where the construction of cemeteries, so dear to liberalism, was advancing slowly and the development arising from Regeneration was already being felt.

The train had arrived in Beja in 1864, while construction work on the line was already underway in the Algarve. In turn, the macadamized highway was a reality between Loulé and Faro and on the now designated EN125 (at the time Estrada Real n.º78).

It is true that the sea continued to constitute the «road» connecting the Algarve to Lisbon and the world. So, as always, it was by boat that the material and cultural “news” reached the Algarve.

Aires Guedes Coutinho de Garrido (1805-1874), born in Penela and graduated in law, took office as civil governor of Faro on May 8, 1866, visit the district and present a summary of what he had seen to the government, presided over by Joaquim António de Aguiar.

The report, completed on April 24, 1867, was divided into two parts: the first, specifically on each municipality [management of municipal and parish services (predecessors of parish councils)]; the second dedicated to various branches of public administration present in the territory (education, homeless children and begging, mutual aid associations, pious and benevolent establishments, among others).

Not hiding that he will only say the “pure expression of the truth”, Aires Garrido immediately states that “the administration in general is not good”.

After all, most City Councils were "made up of people who have little or no interest in public improvements" and, even so, it was necessary to ask them to please accept the position, since, due to the tasks they had, they were unable to plenty of time to devote themselves to the public cause.

There were also not many municipal employees and, as a result, the files were not organized (due to lack of cabinets, many documents were kept, in bundles, on the floor on the tiles), nor did most of the books contain opening or closing terms.

Subjects were organized for years and not according to thematic and, not infrequently, it was said that there was no specific document, so as not to look for it, instead opting to ask the civil government for duplicate copies. At the level of Parish Councils, the situation was similar.

Most had no annual income and expense budgets, "the lack of regular writing, the ignorance and indifference of the vogue of most of these corporations" was the rule rather than the exception.

Debt collection was not carried out, "only paid who wanted to", while budgets were still guided by excessive expenses, and other illegal ones. Aires Garrido pointed out that "expenses for dinners and refreshments" were voted on and approved, and there were even parishes with budgets for celebrations for all the saints in the church and "thus other abuses and waste that would be long to enumerate."

As a result, funds were not enough to subsidize schools or necessary charitable works, and often even church vestments on feast days were borrowed from neighboring parishes, even in Spain.

For all this, Garrido promised that "all these aberrations will cease to exist, which, however, requires an improbable work and demands time."

The management of the wheel of the exposed (children abandoned at birth and raised by nannies, subsidized by the municipal councils) shocked that administrative magistrate: «very few will be the districts in which the administration of the exposed is as irregular as I found it in this one, and more than in this I believe nowhere».

No elements were requested from the nannies, in such a way that those who didn't need it were subsidized and, often, it was the mothers themselves who handed over their children and then collected them with the subsidy. The majority moved to a different municipality, since, in the event of the child's death, they would continue to receive support, deceiving the authorities.

According to the report, fraud was the rule in all counties, with the exception of Faro and Tavira. The governor created rules and inspections, immediately extinguishing 8 wheels, with those of Faro, Tavira, Castro Marim, Loulé, Albufeira, Silves and Lagoa. As of June 30, 1866, an estimated 1 children were exposed in the district. The population of the Algarve was 339 people.

In terms of establishments of piety and assistance, there were 17 Misericórdias, of which 9 had a hospital. In Tavira, the hospital did not depend on Misericórdia, that of Espírito Santo, as in Portimão, where “a legacy called S. Nicolau” was administered here by the Third Order of São Francisco.

There were also 15 mutual aid associations (9 composed exclusively of fishermen – maritime commitments and 6 of artists and workers), 3 common granaries (they lent cereals at an interest to farmers) and 109 confraternities or third-party orders of various invocations.

If it was a question of associative institutions, their management was no better than that existing in municipalities or parishes.

In the case of the Misericórdias, the budgets were, as a rule, disproportionate between the “expenses intended for acts of charity and those applied to festivities and suffrages, for the most part not authorized by the statutes and foreign to the nature of these establishments”.

There were institutions that had more employees, and as if that wasn't enough, many were gratified for services that they had to do for free, among other irregularities.

As a result, with the exception of Faro and Tavira, the buildings where the sick were received were cramped, devoid of furniture and clothing, with some, according to Aires Garrido, who had visited all of them, with a disgusting appearance.

However, there were also good examples, such as the Hospitals of Misericórdias de Lagoa and Loulé, which underwent improvements during those years, at the initiative of local benefactors, or even the one in Portimão. Of the existing confraternities, that magistrate eliminated several, and among them there was one that scandalized him, that of Nossa Senhora dos Mártires, of Castro Marim.

From the outset, he had not presented accounts for more than ten years, then with an annual income of around 1000$000 réis, which was fully spent on the annual solemnity of Our Lady, "in the shadow of which the most scandalous debasements have been practiced". Because, despite the large amount, the amount was not enough, so he proposed the sale of jewels and even so “there was a presumable deficit of 26$000 réis in the same budget”. Accounts sent to be "competently judged".

Given this appetite for parties, it seems that poverty was not a problem. In the district, 2.783 people lived exclusively from begging in the streets, of which 544 were under 14 years of age. To which were added another 1.673 who did not beg, but lived on public charity (246 aged 14 years or less).

However, nothing that scandalized society or confraternities, as we have seen.

The governor attributed this scourge to various origins. In the case of children, they came mostly from the exposed who at the age of 7 were given to the nannies who raised them. These belonged mostly to the poorer classes, did not provide them with education, nor put them to learn trades, beginning early to beg in favor of these same nannies, a habit that they would not lose in adults.

Then, if the kids suffered from any illness, they looked for the nurses that it would not be cured, "to attract more compassion and public benevolence", which did not only happen with those exposed, "but also, unfortunately, they practice some parents to with the children".

On the other hand, the indolence and recklessness of the maritime class, which were very numerous and which, in adverse conditions (rough seas, or when fishing was scarce), had no other recourse but alms. We were still very far from social support: these only arrived after April 25, 1974.

The almost inexistence of factories and workshops also contributed to this harsh reality, reminding that magistrate that, with the exception of three or four establishments, where cork was prepared for export, «there is not a single factory in the district».

There were also bad agricultural practices (the land was not prepared, fertilized or watered, the machines were unknown and the seeds were not selected) and many uncultivated lands, the governor lamenting that the absence of roads did not allow transport and with it the trade of agricultural products.

All this without forgetting education. Of a total of 28 844 children aged 6 to 14, only 2 211 attended school regularly, ie, not even 8% of the total. There were 48 public and 14 private male schools in the region, while for females there were 5 public schools (one still not functioning) and 11 private ones.

Such numbers led Aires Garrido to deplore the poverty, ignorance and prejudice of the majority of the Algarve, who preferred to send their children to agricultural work or fishing to the detriment of school, not forgetting that there were others, not for lack of resources, but that they wanted their children not to receive "any instruction, so as not to be bothered with the service of jurys and unpaid public office."

Municipalities and parishes also did not encourage school attendance. They even had, according to the governor, "reluctance to vote on subsidies for houses and furniture for the creation of new schools" and as a rule the buildings were bad, "without floors, lack of light and clothing". In turn, the low salary of teachers did not attract the most qualified people for the profession and even less for hidden places, as was the majority of the Algarve at that time.

Faced with this bleak scenario, the civil governor pointed out safety as positive: "thanks to the good nature of these peoples, the most serious crimes in the district are rare." It only indicated, since its arrival to Faro, two criminal facts, a murder and an attempted robbery, with burglary at night.

The first, although committed by a foreigner, was arrested in the act and the individuals indicted in the second were equally captured all on the same day.

However, he still had a final constraint that he did not hide: most of the Algarve lacked «the disposition and the necessary interest to assist the authority's action in carrying out many improvements to be undertaken», to which he added, «these are causes that very powerfully impede may everything be achieved with the brevity that would be so desired».

With mediocre politicians, incapable officials and a small retrograde elite occupying positions in the various associations, more concerned with the foam of the days, or rather with itself, in "dinners and refreshments", to the detriment of investments in education, in the fight against poverty, or even materials, in short of outlining a strategy for change, the Algarve of 1867 was anything but idyllic or cosmopolitan.

Ignorance, smart-ass and indifference reigned.

More than 150 years later, many practices and thoughts are recognized in our days that remind us that time is running fast, but mentalities do not change so rapidly.

But, after all, what did Aires Garrido tell the government specifically about each municipality? That's what we're going to tell you in the coming weeks. Demolition portraits of another reality lost in the annals of regional history.

(Go on)

Author Aurélio Nuno Cabrita is an environmental engineer and researcher of local and regional history, as well as a regular collaborator of the Sul Informação.

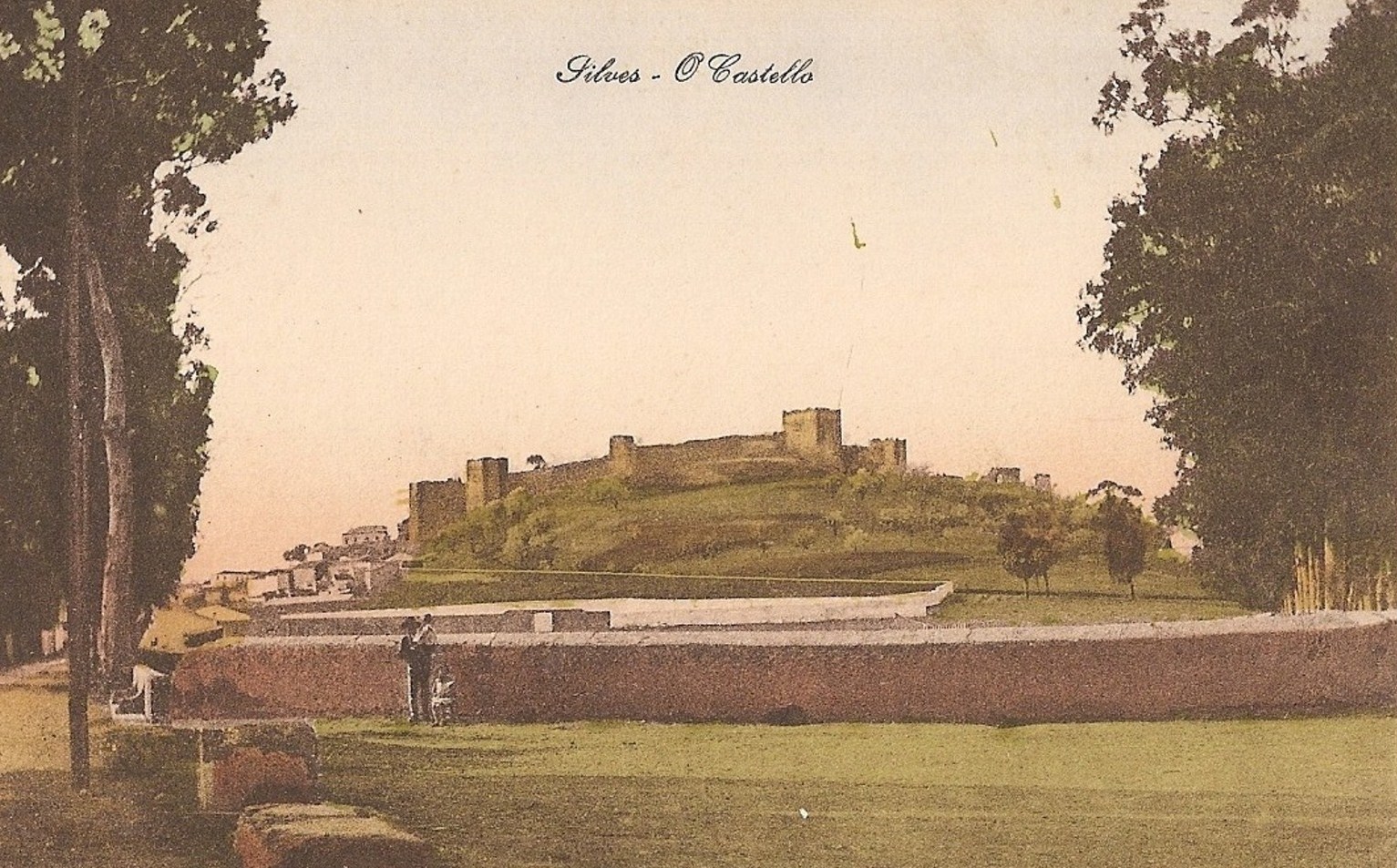

Note: In the transcripts, the spelling of the time was maintained. The images used are merely illustrative and correspond to illustrated postcards from the last decade of the XNUMXth century and/or early XNUMXth century.

Comments