What's in common between a sedentary life with lots of chairs and sofas and little exercise, a diet rich in fat and sugar, and the big belly of that Uncle who drinks too much and spoils Christmas parties? Nothing more, nothing less than a history of bad livers.

It is well known that too much alcohol is harmful to the liver. Everyone has heard of cirrhosis caused by excessive alcohol consumption. But fewer people know that, even in people with little (or no) alcohol consumption, the liver can be affected in a way very similar to someone with an excessive consumption of alcohol. It's because?

Even before the covid-19 pandemic, we knew we had another pandemic on our hands. Poor lifestyles in industrialized countries, with sedentary lives, often clinging to screens and with little or no physical exercise, associated with deficient diets, rich in sugars and fats, have led to an increasing increase in metabolic disorders, including the so-called syndrome metabolic, which is accompanied by serious conditions. One of these conditions is the so-called non-alcoholic fatty liver, that is, an excessive accumulation of fat in the liver, which occurs in situations of zero or reduced alcohol consumption.

It is useful to open a parenthesis here and say that the notion of “reduced alcohol consumption” can have several definitions according to the person who tells the story. A daily bottle of red wine for some people may be a classic definition of reduced alcohol consumption (it isn't!), hence the term “non-alcoholic” may have a dubious connotation in some circles.

Going back to our story, what causes the liver to accumulate fat excessively? The answer is not linear, but includes the aforementioned “evil life”, as the Xutos e Pontapés would say.

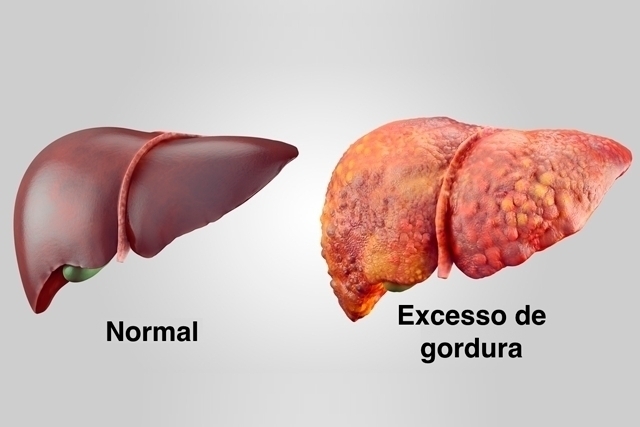

Under normal conditions, in an active life, our liver accumulates only the minimum fat reserves necessary for its daily functioning. The main cells in the liver, called hepatocytes, burn this fat to generate the energy that organ needs.

When we have a diet that is very high in fat and we don't burn it with physical activity, our body stores the excess in a specialized tissue called adipose tissue. When it reaches full capacity, fat begins to accumulate elsewhere, including the liver.

Let's now add to this mixture a diet rich in those wonderful sweets from the shop windows, in soft drinks, and many other foods rich in sugar. This extra addition of sugar (sucrose, in the most scientific term) leads to an exaggerated increase in liver fat.

It's because? Because sucrose has fructose in its composition (exactly, fruit sugar), which, in excess, has very serious consequences for our body. Excess fructose is quickly stored in the liver in the form of fat and can also alter our intestinal flora, leading the friendly microorganisms that use our intestines for their private condominium, to produce toxins that then travel to the liver and can cause more damage.

The increase in liver fat mentioned above will be greater the less active we are, precisely because we cannot burn this energy source.

Here we have a condition called steatosis, which, in its onset, is the benign stage of the so-called fatty liver syndrome. And at this stage we still have the choice to improve our diet and increase exercise to reverse the process.

We can, of course, think that this is all a lot of work and continue our less healthy life. Our liver, with a lot of fat and on top of receiving toxins from other places, such as the intestine, can become inflamed, leading to the so-called steatohepatitis, a much more severe condition and still without effective treatment.

We can continue to ignore the problem, have the same (bad) lifestyle habits, and slowly our liver can develop cirrhosis. Look, we're talking about non-alcoholic fatty liver, it's not just Uncle we talked about above who can have cirrhosis because he abuses the “glass”. We can suffer from cirrhotic liver without drinking alcohol, strangely enough.

If, even so, there is no judgment, a consequence is a hepatocarcinoma (a tumor in the liver), whose treatment can involve the removal of part of the liver or even a transplant.

Yeah, I hope you've noticed the problem now; moreover, diagnostic methods that can help the doctor to identify the problem at an early stage do not exist.

For those who are even more incredulous, note that around 30% of the Portuguese population may suffer from non-alcoholic fatty liver (a figure similar to that of the European Union).

More worryingly, about 10% (!!) of children up to 12 years old can suffer from this condition. Imagine what will happen when they become adults if they continue with a less healthy lifestyle.

Imagine now: a pandemic that forces everyone to spend more time at home, that takes children away from schools, from their physical and sports activities, from playing with friends until sunset, and glues them to computer or television screens or all day.

Imagine that adults go out less and do (even) less physical activity. This will only get worse, and a communicable epidemic will be followed by an even worse non-communicable one.

For the curious: the European FOIE GRAS project, coordinated by the Center for Neuroscience and Cell Biology of the University of Coimbra and with several international partners, explores the reason for this condition, identifies biomarkers that allow it to be more accurately diagnosed, and develops new treatments.

Furthermore, it produces fantastic content for society, including two comics: a more recent one with the title “A Balanced Liver is Half the Way!” and another published under the European University Games, which took place in Coimbra in 2018.

For more information about fatty liver, see the FOIE GRAS project by clicking here.

Author Paulo J. Oliveira graduated in Biochemistry in 1999 at the University of Coimbra, Portugal, where he also obtained his PhD in Cell Biology.

He is currently Principal Investigator at the Center for Neuroscience and Cell Biology at the University of Coimbra and leader of the laboratory MitoXT – Toxicology and Experimental Mitochondrial Therapeutics.

In addition to his research work, with more than 215 peer-reviewed publications, Paulo Oliveira is Visiting Assistant Professor at the University of Coimbra, as well as at other Universities inside and outside Portugal.

Comments