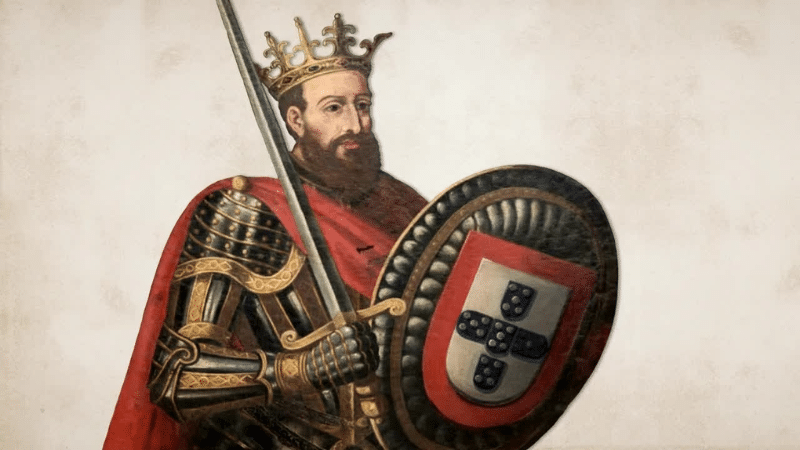

The kingdom of Portugal began on October 5, 1143, with the celebration of the Treaty of Zamora, between D. Afonso Henriques (1109? – 1185) and King Afonso VII de Leão, who was his cousin. But the first Portuguese king had already called himself king since 1140. The first capital of the kingdom was Coimbra, where D. Afonso Henriques died and is buried.

How was Astronomy in the time of D. Afonso Henriques? In 1090, long before nationality, the Mozarabic bishop of Coimbra, D. Paterno, donated two astrolabes to the Cathedral he directed. This act shows the existence of scientific knowledge in the first Portuguese capital, before there was a kingdom and long before there was a University (this only appeared in 1290 in Lisbon, with a first transfer to Coimbra in 1308).

Mozarabs were Iberian Christians who lived under the Muslim rule of Al-Andaluz: they were Christians who spoke Arabic and of Arabic culture. Most likely, there was a Mozarabic school associated with that Cathedral of Coimbra, where, among other subjects, elements of astronomy would be taught. Coimbra was conquered by the Christians in 1064 by Fernando I of Leão, the Great, and in 1096 it was integrated into the Portucalense County.

The astrolabe, an instrument used to measure the height of the stars, is a Greek invention that was perfected by the Arabs. These reigned in science at the time when D. Afonso Henriques created the kingdom of Portugal.

In the eleventh century, astronomers Abu Buzjani, Avicenna, Al Biruni and Alhazem, all active in the Middle East, where Iran and Iraq are today, shined. And, in the eleventh century, he pontificated Averroes, a great commentator on Aristotle who was born in Cordoba.

Toledo was one of the centers of Arab science: with its reconquest in 1085 by Alfonso VI de Leão, Arabic knowledge began to pass on to Christians. One of the greatest translators of Arabic books into Latin was Gerardo de Cremona, a contemporary scholar of the founding of Portuguese nationality who, although born in Italy, worked in Toledo for many years.

His major work is the Arabic translation of the Almagest, which was originally written in Greek by Ptolemy of Alexandria in the second century. This book describes the geocentric system, which dominated throughout the Middle Ages, as it only began to give way to the heliocentric system in 1543, when Copernicus' famous book came to light.

In Christian Coimbra, knowledge was closely linked to the monastery of Santa Cruz, which was founded in 1131, even before nationality, by the Order of Canons Regular of St. Augustine.

There was an important library there (mostly today in the Public Library of Porto, taken by Alexandre Herculano in the XNUMXth century), with astronomical works, as in the Cathedral of Coimbra and other ecclesial institutions.

For example, in the Monastery of Alcobaça there was the Treaty of the Sphere (1271), by the Englishman João de Sacrobosco, which was a reference work on astronomy until very late.

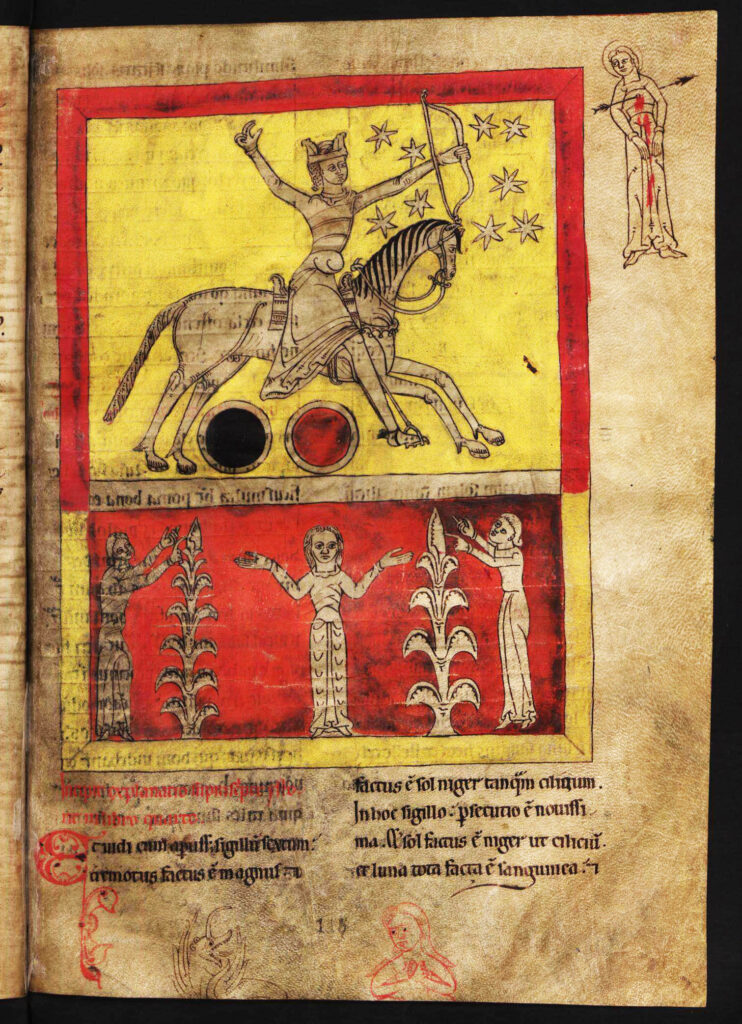

A notable work that, not being astronomical, includes representations of the moon and stars is the Apocalypse of Lorvão, an illuminated manuscript from 1189 (from the time of D. Sancho I), existing in the Monastery of Lorvão, near Coimbra. The moon and stars are also depicted on some first dynasty coins.

The planets known in the Middle Ages were, in addition to Earth, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. So, these planets were called stars, even though they are mobile, unlike fixed stars.

There was no notion of a comet, but it is known today that the Halley passed through Earth in 1145, during the reign of Afonso Henriques. In 1147, before the taking of Santarém from the Muslims by D. Afonso Henriques, another comet was observed. According to Duarte Galvão, author of the Chronicle of the King D. Afonso Henriques, written at the beginning of the 1419th century, the warriors saw “a kind of bull going through Heaven, carrying comas of fire, from the head to the tip of the tail”. The same description is corroborated by the Chronicle of Portugal of XNUMX, by an anonymous author, which calls the comet “serpent” instead of “bull”.

Three days before the comet, the same warriors observed what is now called a meteor, or “shooting star”. The meteorite was considered by the Portuguese as an omen of the sky that was favorable to them. The fact is that D. Afonso Henriques, who came from Coimbra, conquered Santarém on March 15, 1147.

Astronomical events such as this caused awe and terror, but there were others: for example, one of the first eclipses observed in the Portuguese kingdom occurred in 1199, during the reign of D. Sancho I, when the Moon completely covered the Sun and caused panic in the population.

In the Middle Ages, astronomy was confused with astrology, although the Church has always fought prognostications made in the name of determinism, in favor of free will. Several early Portuguese kings of the first dynasty used the advice of astrologers. But King Duarte, in his Loyal Counselor, criticized this procedure.

In conclusion: Astronomy in Portugal is much older than the Discoveries, when the nautical astrolabe appeared and maritime charts based on astronomical and geographical observations were started.

Author Carlos Fiolhais is a physicist

Comments