This year, in October, marks the 160th anniversary of the beginning of Psychophysics, a sub-area of Psychology dedicated to the study of the mathematical relationships between the intensity of a stimulus and the magnitude of the sensation caused by that trigger. Learn more about this area and its founder, German physicist Gustav Fechner.

A little over a century and a half ago, on the morning of October 22, 1860, Gustav Fechner, a German physicist, and as told by himself, had an innovative idea that would inaugurate Psychophysics and, therefore, lay the foundations of Psychological Sciences.

Psychophysics is usually defined as the sub-area of Psychology dedicated to the study and clarification of the mathematical relationships between the intensity of physical stimuli (objective quantities) and the magnitude of the corresponding sensations (subjective quantities). For Fechner, who multiplied his career between satirical writings (under the pseudonym of Dr. Mises) and an interest in Philosophy, postulating a mathematical function that captured the relationship between physical and sensory intensities would be a decisive step towards solving the mind problem. -body.

For this, the main issue to be resolved would be related to the measurement of subjective, unobservable sensations.

While for the measurement of objective quantities there were already well-established procedures and adequate measurement units, the same could not be said about sensations, of a subjective nature and not directly observable.

To resolve this issue, Fechner would draw on the work of a colleague of his at the University of Leipzig – Ernst Weber. The latter had conducted a series of studies on the sensation and perception of weight, in which human subjects took turns lifting objects with slightly different weights and were asked which one felt heavier or lighter.

Weber noted that the minimum increment necessary for any given weight to be discernibly heavier would always be a constant fraction of the initial weight. For example, a weight of 1kg should be added at least 70g to make it look slightly heavier (ie a weight of 1kg and a weight of 1.06kg are perceptually identical, as the difference is less than 70g) .

However, at a weight of 5Kg the minimum increment that is only discernible is 350g; a weight of 10Kg should be increased by 700g to make it look heavier, and so on.

In all these cases, the increment in grams increases, but remains as a constant fraction of the initial weight: 0.07. In other words, in the sense of weight, any object should be 7% heavier for the difference to be discernible.

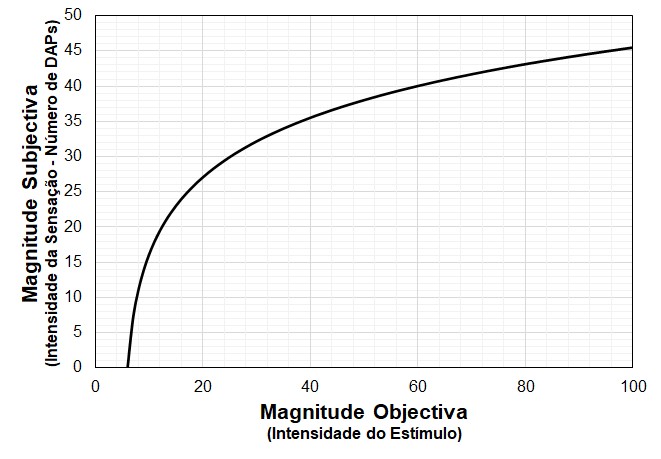

Central to Weber's data is the concept of differential threshold and, above all, the notion of “just noticeable difference” or DAP. Returning to Fechner's idea, what Fechner hypothesized was simply that DAP could be taken as measurement units of subjective sensations - as each DAP constitutes the point at which there is a distinct sensation, then it would be enough to count, for any physical magnitude, the number of DAPs contained in this value.

Note that the 0.07 fraction applies to heaviness sensation, and other sensory modalities could be described with other values (Weber's fraction is, strictly speaking, taken as a measure of sensitivity – sensory modalities with smaller fractions are more sensitive to variations in intensity).

For example, we are particularly good at visually discriminating area differences between geometric figures (Weber fraction of 0.06), differences in line length (fraction of 0.03), red saturation differences (fraction of 0.02) or differences in brightness intensity (fraction of 0.08).

By contrast, larger increments in the physical intensity of a stimulus are needed so that we can discriminate between savory flavors (fraction 0.14), sweets (fraction 0.17) or aromas (fraction 0.24).

Regardless of the value of the Weber fraction for any sensory modality, the use of DAPs as a measurement unit invariably results in the same conclusion: the relationship between physical intensities of any stimulus to which we are sensitive and the sensory magnitude is a negatively logarithmic function. accelerated – a conclusion that came to be known under the name of Fechner's Law.

It should be noted that, more than a century earlier, Daniel Bernoulli, a Swiss mathematician and physicist, had already proposed a similar relationship between the objective value of monetary goods and the subjective utility associated with them.

For Fechner, the logarithmic relationship between objective quantities and subjective intensities would constitute the basis from which psychological phenomena could be understood, and would explain several aspects about our relationship with virtually any stimulus: a lit candle has little impact on the luminosity of a room with a lamp on, but its glow is clearly noticeable if lit in the dark; earning 100 euros when you have a zero account has much more impact than the same gain when you are a millionaire; a sound system playing music is much more noticeably audible in the silence of dawn than in the middle of the day; etc.

An example of how Fechner's Law is currently implemented in mobile devices is the automatic variation of the brightness of some screens depending on the ambient brightness, in order to reduce energy consumption. Another example is given by the decibel scale, purposefully a logarithmic relation of the sound pressure to convey the perceptible sound of a given noise source.

As already mentioned, Fechner's works, and in particular his work “Elements of Psychophysics”, would come to form part of the foundations of Psychological Sciences, not only because of the homonymous law, but because he established several methods for measuring sensory thresholds ( and hence DAPs).

Although, later, Fechner's Law was questioned and revised, the methods developed by him for the measurement of subjective magnitudes not only remained important tools in the most diverse areas of Psychological Sciences, but were also applied to other sciences, such as o are Orthoptics (eg, the Snellen table, with letters printed in different sizes that must be identified by the patient) and Audiology (eg, to obtain an audiogram).

Author Nuno de Sá Teixeira graduated in Psychology from the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences of the University of Coimbra, and a Ph.D. in Experimental Psychology from the same institution.

He has worked as a PhD researcher at the Department of General Experimental Psychology at the University Johannes-Gutenberg, Mainz, Germany, at the Institute of Cognitive Psychology at the University of Coimbra and at the Center for Spatial Biomedicine at the University of Rome 'Tor Vergata', Italy.

He is currently Visiting Assistant Professor at the Department of Education and Psychology at the University of Aveiro.

His scientific work has focused on the study of how physical variables (in particular, gravity) are instantiated by the brain, as “internal models”, to support perceptual and motor functions in the interaction with the world.

Thus, his interests depart from the hinge between thematic areas such as the Psychology of Perception, Psychophysics and Neurosciences.

Science in the Regional Press – Ciência Viva

Comments