The 70s of the 1875th century were dramatic for the Algarve. Consecutive years of drought sounded alarm bells in the capital of the kingdom, Lisbon, in May XNUMX.

The 70s of the 1875th century were dramatic for the Algarve. Consecutive years of drought sounded alarm bells in the capital of the kingdom, Lisbon, in May XNUMX.

In fact, the Mediterranean climate, where the Algarve is located, is characterized by low and irregular rainfall, with frequent drought years, alternating with more humid, with floods and floods. However, the drought in those years became dire and with it hunger and thirst threatened to annihilate the Algarve.

On July 15, 1874, the Lacobrigense periodical “Gazeta do Algarve” reported on the extraordinary drought that was felt in the region: “which sterilized our fields, destroyed important irrigation systems and impoverished sources that never accused the lack or absolute lack of water ”.

But if that agricultural year was not missed, 1875 would be dramatic. The sky did not shed a drop of water, especially in the barrocal and coastal areas, in such a way that, in the April 21, 1875 issue, the same newspaper foreshadowed "with the speed of the success of time we are heading towards a frightening food crisis". and then add that "there is no longer any hope that agriculture will produce enough to sustain the inhabitants of the province, nor will there be enough pastures to feed the cattle."

On June 2, the same periodical took stock of the harvests in the area of Lagos, saying that the production was so low that, from the harvests, a seed and a half resulted, and, from the trees, it was foreseen a quarter of what would be harvested in a normal year. In short, a calamity befell the Algarve.

With subsistence agriculture, two bad agricultural years compromised not only all food, but also made new planting impossible. After all, despite having been thrown to the ground, the seeds did not germinate, or, if that happened, did not generate new seed. Trees also threatened to dry up, especially fig trees, which were essential in the regional economy, jeopardizing annual production and those of several subsequent years.

In a time that was still distant for the welfare state, where the main activity of governance was tax collection, the catastrophic situation in the region, combined with the piercing cries of the Algarve, forced the government to act.

Thus, by ordinance of May 15, 1875, the civil governor, the lawyer José de Beires (Lamego, 1825-Lisbon, 1895), was ordered to cover the entire district in order to gather accurate information about the damage caused by the lack. of rains.

That magistrate left Faro on May 23, starting the visit in Vila do Bispo, and successively visited all the county seats and most parishes in the region, returning to the Algarve capital on June 10th.

It is difficult for us to imagine the conditions of the trip. For, if, on the one hand, following the Regeneration, the construction of some macadamized roads was advancing, on the other hand the slowness of the work and the scarce resources made the old medieval roads predominate, almost always footpaths.

As for the railway, in addition to a small ghost section, built between Faro and Boliqueime, did not descend beyond Casével (Castro Verde), then the station that served the Algarve.

José de Beires met with the local authorities (city council and municipal council), the largest building taxpayers, parish priests and governors, traveling to one or another village to find out in loco the consequences of the long drought.

At the meetings, he collected information about the gravity of the situation, as well as proposals to alleviate the crisis. His visit resulted in a long and detailed report that he sent to the government, describing the agricultural, economic and social situation of all parishes and municipalities in the Algarve. Exposition complemented with suggestions that it considered pertinent to execute in order to avoid the indigence of the Algarve.

The thoroughness of its description allows us today to know not only the effects of the drought in all parishes, but also the main crops that were practiced at the time and their productivity in regular years. It is, therefore, supported by the pen of that magistrate, whose report was published in the “Gazeta do Algarve”, that we propose to revisit the Algarve between 23 May and 10 June 1875.

As mentioned, the governor began his tour of the council of Vila do Bispo. This was composed of uncultivated mountains and extensive farmland, the population living almost exclusively on agriculture. As in the entire region, the property was very shared.

Due to the amount of cereals it produced and exported, it was considered the granary of the Algarve. In turn, the number of trees and vineyards was small, only near the villages and for “recreation”, as he said. Still, there were some new fig tree plantations.

As for the effects of drought on Budens, wrote José de Beires:

“In this parish, as in others in the municipality, only wheat, barley, rare rye, grain, chicharo and corn are cultivated. It is, however, in wheat that its main agricultural wealth consists.

The cornfields appeared magnificent at the beginning of the year, and reached, for the most part, a higher development than the cornfields of the other municipalities, especially in the so-called —inner lands — low and green lands, which are therefore less demanding of copious rains. But, in the end, the prolonged drought hampered in some the complete development of the ear and produced its premature death in others, leaving only the hay and some withered grain. It is estimated that the average production will still be 50 percent of a regular harvest. From the later sowings not even the seed is expected”.

Regarding the parishes of foxtail e Vila do Bispo, the situation was identical. as to Sagres:

“It's the parish that suffers the most from the drought. It has the same types of culture, but the damage to the crops is greater.

Production will be lower than in other parishes. There is also an absolute lack of drinking water there. The military detachment that exists in the square of Sagres supplies itself from the Villa do Bispo, which is some 6 kilometers away”.

From the land, some individuals had even emigrated to the mines. In short, it was in Sagres that the drought reached its zenith in the municipality, due to the lack of drinking water. On the other hand, the absence of trees in the municipality did not make it possible to overcome the poor cereal harvest with the fruits.

Once the diagnosis of Vila do Bispo was made, José de Beires went to Aljezur. In the county, the trees were scarce, olive trees, cork oaks and orange trees were the main trees. The vines were also tiny here.

On Bordeira wrote:

“This parish is located in the interior of the mountains, and its culture, almost unique, is cereals and corn. On the website of ticker, one of the best in the parish, there was already a great shortage of harvests in the previous year, and farmers had to take out loans in order to cover agricultural expenses for the current year. The crops are better than last year's; but in relation to a regular year they will produce a third less. In the rest of the parish, only the lowlands are suffering. Serodia sowings are considered lost.”

in turn, in Aljezur:

“This parish is made up mainly of mountain terrain, largely uncultivated, and an extensive floodplain, land of first quality, whose cultivation, almost exclusive, was rice and corn until 1872. Rice sowing is currently limited to a small area; in the rest it was replaced, first by corn and now by wheat. The crops there promise an abundant harvest, being perhaps the best in the entire district. Even so, the farmers complain about the drought that does not allow them, after the harvests, to use the same land for another planting, as usual. Outside the floodplain, the crops, which are in much greater quantity, offer a meager harvest. It is estimated, therefore, that the general production of the parish will be one third less than that of a regular year.”

In the village flour was already imported, and the sowing of corn, beans and grain predicted a much lower than normal harvest. Already in odeceis, the situation was similar to the county seat.

In general terms, Aljezur was the municipality in the Algarve that suffered the least from the food crisis and the floodplain of the river contributed a lot to that.

Even so, the magistrate noted that the absence of work had led some Aljezurenses to emigrate, which had never happened in previous years.

As a minimization measure, it proposed the construction of a section of the district road from Aljezur, which would pay for work for the working class in the three parishes.

After visiting the municipalities of Vila do Bispo and Aljezur, the civil governor left for Lagos, where he was on the 28th of May.

(Continued)

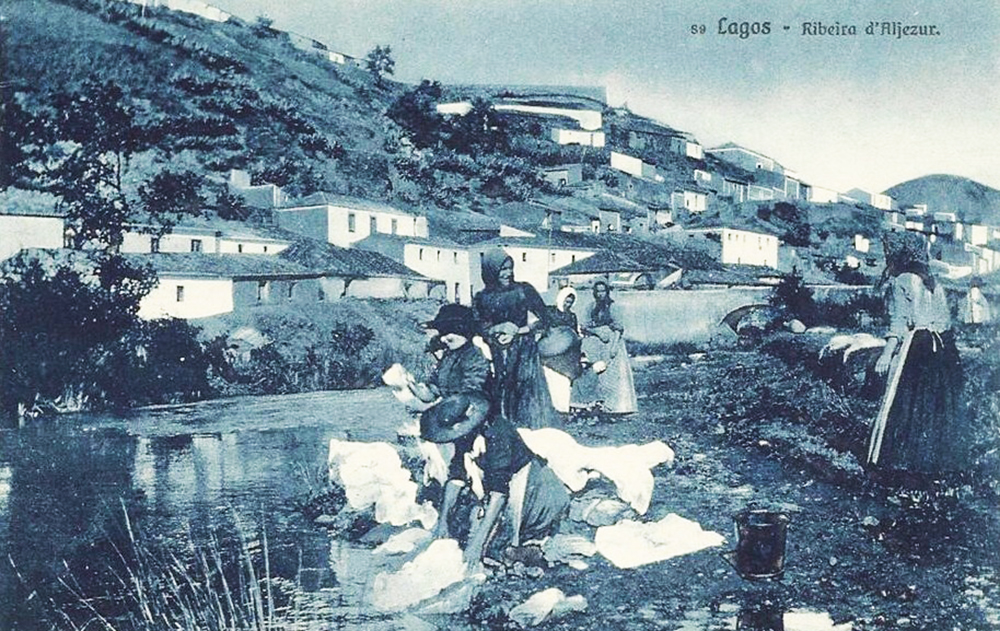

Note 1: The images used, with the exception of the periodical, are merely illustrative. They correspond to illustrated postcards from the first half of the XNUMXth century.

Note 2: In the quotes from the newspaper «Gazeta do Algarve», it was decided to keep the spelling and the period.

Author Aurélio Nuno Cabrita, environmental engineer and researcher of local and regional history, regular collaborator of the Sul Informação

Comments