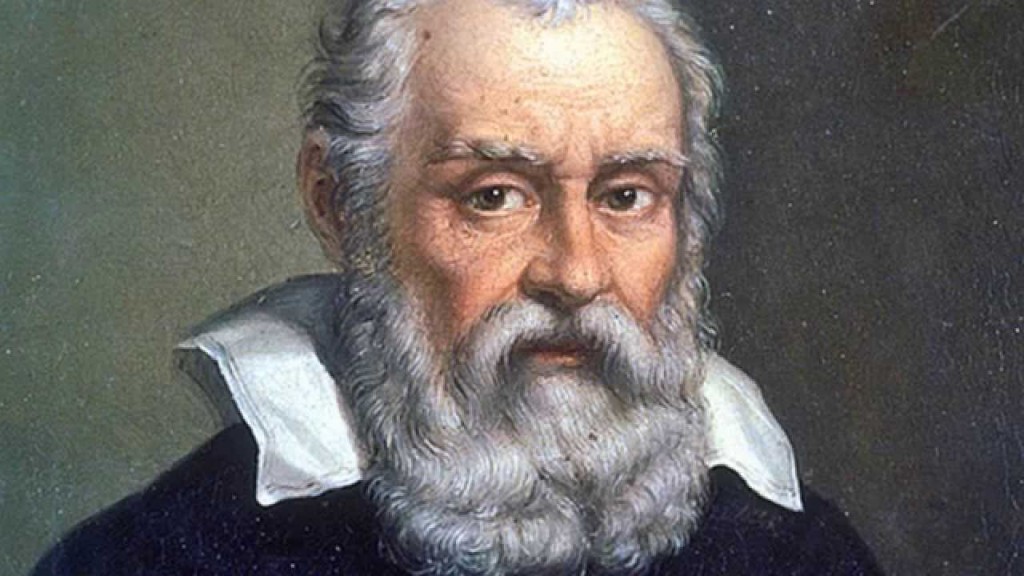

It turned 400 years old last Friday, February 26th, that Gaileu Galilei (1564 – 1642) was warned by the Catholic Church for his opinion in defense of the heliocentric system: it was the Earth that revolved around the Sun and not the other way around, as defended by the Catholic Church and by many academics at the time.

It turned 400 years old last Friday, February 26th, that Gaileu Galilei (1564 – 1642) was warned by the Catholic Church for his opinion in defense of the heliocentric system: it was the Earth that revolved around the Sun and not the other way around, as defended by the Catholic Church and by many academics at the time.

Cardinal Roberto Bellarmino (1542-1621), then an important figure in the Catholic Church, whose Pope at the time was Paul V (1552 – 1621), was entrusted with this mission.

Bellarmino warns Galileo: “that the assertion that the Sun is the immobile center of the world system is rash, almost heretical; that the claim that the Earth moves is theologically wrong; forbids him to speak of heliocentrism as a physical reality, but authorizes him to refer to it only as a mathematical hypothesis”.

It emerges from these accusations that the disagreement between the Catholic Church at the time and Galileo is fundamentally of a theological nature. It's not scientific. The Catholic Church allows Galileo to scientifically refer to heliocentrism. In other words, there was not exactly a fractured confrontation between science and religion as is generalized in common knowledge.

This image of Galileo, father of modern experimental science, as a "martyr of science" at the feet of an authoritarian Catholic Church and contrary to libertarian scientific knowledge, was, according to science historian Patricia Fara, forged during the XNUMXth century by scientific propagandists and it's a very poorly told story.

It should be said, by the way, that Patricia Fara is the author, among other works, of an unavoidable “Science: 4000 of history”, published among us by Livros Horizonte, in 2012, with a preface by Carlos Fiolhais.

A new generation of science historians, in which Patricia Fara belongs, has been trying in recent decades to reconstitute the historical truth of facts and break with the dominant paradigm in Western history of a triumphant science in complete and permanent conflict with religion, in particular the Catholic religion.

It is known today that the prevailing idea, still among us, of a Catholic Church that impeded the development of science, is far from corresponding to historical truth.

As for the episode that actually took place 400 years ago, instead of a direct confrontation between science and religion, or between Galileo and the Pope, it must be considered that that was a more complex conflict and that it involved rival factions within and without. of the Church.

It must be borne in mind that Galileo was a devout Catholic and that he had and continued to have supporters at every step of the clerical hierarchy.

But Galileo had many enemies, mainly because of his enviable social status: he was the first mathematician and philosopher at the court of Cosimo II of Medicis, grand duke of Tuscany and ruler of Florence.

Add to this the fact that many non-clerical scholars and scholars of the time were staunch supporters of Ptolemy's geocentrism, disregarding the works of Copernicus, Tycho Brahe, Kepler and the observational data allowed by Galileo's new revolutionary instrument, the telescope. developed and applied in the discovery and interpretation of the Universe.

Thus, the personal ambitions and rivalries that gravitated towards Galileo are now better known, and there are those who argue that if he had acted in a more diplomatic way and had not written scientific works in Italian, it would be available to others than just scholars. and ecclesiastics, he might have been able to further publicize his heliocentric universe, without having been officially condemned for theological reasons.

Author: António Piedade

Science in the Regional Press – Ciência Viva

Comments