Portuguese neuroscientist Rui Costa and colleagues discovered what happens in the brain before we make a move.

Portuguese neuroscientist Rui Costa and colleagues discovered what happens in the brain before we make a move.

In everyday life, we make countless movements in an almost unconscious way. Walking, running, reaching out to shake hands with someone who greets us, are movements that are part of a neuromuscular repertoire that we have learned and that we have somehow made automatic and “unconscious”.

Understanding how our brain coordinates all the muscles that are involved in these movements and integrates them, in an apparent "conscious effort", with what our eyes see and the sounds our ears pick up around us, among other stimuli, not only does it have a fundamental scientific interest (that of knowing why and how it works), but it also allows us to understand what is actually involved in neurodegenerative diseases that affect movement, such as Parkinson's Disease and Huntington's Chorea.

In other words, understanding which parts of the brain and which neuronal cells are involved in the unconscious decision to raise an arm may allow us to find new therapeutic strategies to treat or at least alleviate the symptoms of those disabling diseases.

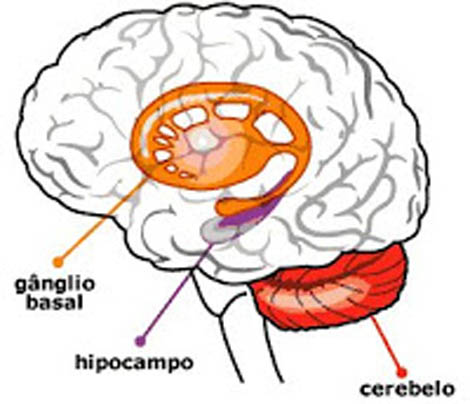

Two different neuronal circuits emanating from the basal ganglia (a group of nuclei of neurons located deep in the brain) were known to affect the decision to initiate a movement.

One of the circuits is called “direct” and the other, because it has other ramifications, is called “indirect”. Parkinson's disease, which inhibits movement, and Huntington's Chorea, which causes uncontrolled movement, affect these two circuits. Therefore, neuroscientists put as a theoretical hypothesis that the direct circuit served to activate the movement and the indirect one served to inhibit it.

But an investigation in which the Portuguese neuroscientist Rui Costa (who works at the Champalimaud Foundation, in Lisbon) participated, reported in an article that has just been published in the online edition of the journal Nature (doi:10.1038/nature11846), shows that, after all, the command to start an action is more complex than previously thought.

Rui Costa and colleagues found that the decision to make a simple movement, such as lifting the arm, depends on two different neuronal circuits and not just one.

According to the Portuguese researcher, “scientific knowledge so far indicated that the direct circuit promoted movement and the indirect circuit inhibited movement. Therefore, in the case of Parkinson, it would be an excess of indirect circuit activity which caused the lack of movement”.

In this work, considered very elegant from a laboratory and scientific point of view in an editorial in the prestigious journal Nature, the researchers introduced fluorescent proteins and optic fibers into laboratory mice, which allowed them to directly visualize the activity of the basal ganglia, which they never had before. been done.

In this work, considered very elegant from a laboratory and scientific point of view in an editorial in the prestigious journal Nature, the researchers introduced fluorescent proteins and optic fibers into laboratory mice, which allowed them to directly visualize the activity of the basal ganglia, which they never had before. been done.

This monitoring allowed see and realize that “these two circuits didn't work in the opposite way, but more in a coordinated way. When there is movement, both circuits are more active and therefore what indicates is that, if we discover ways to manipulate these circuits to be active in a coordinated way, we can improve movement problems, such as Parkinson or Huntington”, explained Rui Costa.

These results may help "to improve the treatment of symptoms of neuronal diseases", says the researcher, adding that "the next step is to try to manipulate the activity of these circuits, in order to control movement".

We are thus closer to realizing the neuronal orchestration that precedes a gesture.

Author Antonio Piedade

Comments