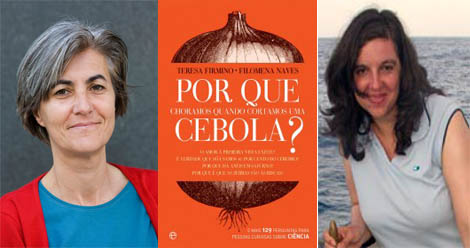

Interview with Teresa Firmino and Filomena Naves, science journalists from the Público and Diário de Notícias newspapers, respectively, regarding their latest science dissemination book that has just been published by the publisher A Esfera dos Livros, entitled “Why we cry When Do We Cut an Onion?”.

Interview with Teresa Firmino and Filomena Naves, science journalists from the Público and Diário de Notícias newspapers, respectively, regarding their latest science dissemination book that has just been published by the publisher A Esfera dos Livros, entitled “Why we cry When Do We Cut an Onion?”.

António Piedade – Why did you write this book now?

Teresa Firmino– It came from an invitation from the publisher, the Sphere of Books, which we accepted as a fun adventure. The idea was to answer everyday questions that we all ask, but then we end up not looking for an answer. Some are questions about common aspects of everyday life, starting with the reason for being the aggression of the onion in our eyes, the chili peppers or the eggs not sticking to the pans, or at least to some of them. Others are not so commonplace, such as the fate of the Universe, if there is life on other planets outside the solar system, or what is the deepest place in the oceans.

Philomena Ships– This was a challenge that Esfera dos Livros published last year. We thought it was a great idea and took the opportunity to go after our own curiosity. Our friends, in some very lively conversations, also made us some good suggestions.

AP – Who wrote this book for and who are these “curious people” for whom the book is destined?

AP – Who wrote this book for and who are these “curious people” for whom the book is destined?

TF – This book is for the general public, from 9 to 99 years old. You don't need to know a lot of science to read it, because the language is simple and easy to understand. We wanted to pique everyone's curiosity by answering the questions that we or our friends have ever asked. It's a why book. And, to answer them, we turn to the explanations given by scientists. Even for the little ones, parents, after reading the answers, can explain to them the many mysteries this book is about in an even simpler way.

We also wanted him to tell stories, some related to Portugal, which was a way of making the book different from others and bringing him closer to Portuguese readers. You also don't have to read it end to end. You can jump to the questions you are most curious about and the answers are generally short.

FN – This book is aimed at a wide audience and people of almost all ages. We've written it in a simple and accessible way, and we think it's interesting, precisely with the aim of making its reading appealing and arousing interest in science and in the issues that are the object of its search.

AP – What response to your challenge do you expect from readers?

TF – That they have fun reading the book and that, along the way, they let themselves be captivated by science and its wonderful and inspiring aspects. Knowing that there may be life in other parts of the Universe is inspiring, as knowing that our Sun is going to die is a way to put everything in perspective. Science seeks to unravel the mysteries of nature and the answers it finds do not diminish in any way the beauty of things, on the contrary. This constant search for knowledge is part of the essence of being human and science shapes the way we see the world and even make personal choices, in aspects as simple as not giving up taking an antibiotic halfway through.

FN – If people are interested, and if he can arouse more curiosity about the things of science, that will certainly be a good answer.

AP – What led you to choose the six territories in which the same number of chapters in your book are developed?

TF – It was a way to organize all the questions we had. We noticed that they could be organized into six themes or, as you say, into six territories. One of these territories refers to what is above our heads – space and astronomy – the other to phenomena on planet Earth. We do not forget the territory of animals, nor that of worldliness, nor the anxieties and mysteries about ourselves. Closing the book are myths and curiosities, starting with the idea that the size of the feet can indicate the size of the penis and ending with the legend that D. Afonso Henriques beat his mother.

FN – We decided early on that it would be more useful, even in terms of readability, to have large areas that allow readers a more immediate and simple “navigation” of the book. We think that the six areas end up covering almost everything: the universe and space, the Earth in its various dimensions, living beings, the human being and its complexities and also some myths and curiosities of everyday life.

AP – What criteria did you use in choosing the 130 questions?

AP – What criteria did you use in choosing the 130 questions?

TF – The choice of questions resulted from many conversations between the two of us and also with our friends, whom we asked to say what they would like to see answered. We tried to make the book diversified and thus came up with 129 questions about science, plus one about the onion, which is in the title.

FN – We talked with friends and exercised our curiosity, as I said, but we also tried to tell some stories through these questions. Some questions are here because their answers revealed themselves to us through fascinating stories. The truth is that science and scientific pursuit are full of fantastic stories.

AP – Is this book an extension, a complement, of your intense scientific journalism activity?

TF – Undoubtedly, this book stems from our activity as science journalists. Every day, in our newspapers, I in “Público” and Filomena Naves in “Diário de Notícias” write about scientific news for readers. We seek to decode science and the discoveries that have just been made, which are often hermetic and arid, using language that is understandable and, whenever possible, pleasant to read. It is also this bridge between science and the reader, in this case for everyday curiosities, that we tried to make in the book.

FN - I think so. In journalism, one of the essential criteria for publishing something is the fact that something is news. Here there is no such constraint, so to speak. The book is therefore more comprehensive and, in this sense, it can be said that it is an extension of our activity as science journalists.

AP – How do you classify the production of science and technology in Portugal since the 25th of April 1974?

TF – It has grown tremendously. And it wasn't just scientific production, the number of doctorates and the percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) spent on science and development (R&D) also increased. The way science is done in the country has also changed since the 25th of April. It was closed to the rest of the world, often made by a scientist alone and isolated, but in the meantime it became internationalized, with the adhesion to international organizations such as the European Laboratory for Particle Physics (CERN) or the European Space Agency, and many young people went to obtain a doctorate abroad.

Currently, the big question is whether, with the crisis and with less money, it will be possible to maintain, at least, scientific production and other indicators, such as GDP spent on R&D.

FN – A remarkable growth, which resulted directly from the political and financial investment that was made in this area and which today allows Portugal to be a scientific partner in different areas at an international level. This, it seems to me, is a fairly consensual idea today.

AP – Would it be possible to carry out the same exercise (that of writing a science dissemination book that gives “voice” to Portuguese scientists) when you started your activity as science journalists?

TF - It seems to me that it would have already been possible, because there were good Portuguese scientists and they had news and stories to tell. I became a journalist at that time, in 1992, almost right from the start in the field of science, and the difference I noticed over these years is that there are now more Portuguese researchers publishing results in international scientific journals. That is, journalists have more investigations to write about. And scientists are not only more used to talking to journalists, they want to publicize their work. They consider it part of their role to communicate to citizens what they are doing and one way to do this is by talking to journalists.

FN – I started working in this area in 1986, in the now extinct “Semanário”, just when the growth of scientific activity in Portugal began. At that time there were already some good examples of scientists and scientific groups working in the country, and I was just looking for them, to be able to report their work, but it would not have been possible to write a book like this at the time, with so many "voices" of Portuguese scientists.

Degree: Why do we cry when we cut an onion?

Authors: Teresa Firmino and Filomena Naves

Publishing company: The Sphere of Books

Collection: Out of Collection

Number of pages: 264

ISBN:978-989-626-397-3

Order date: July 2012

http://www.esferadoslivros.pt/livros.php?id_li=316

Interview author: Antonio Piedade

Science in the Regional Press – Ciência Viva

Comments