A look at the dictatorship reveals a generally “well-behaved” regional press, which featured exceptional examples of resistance, such as the newspapers “Comércio do Funchal”, “Jornal do Fundão” and “Notícias da Amadora”.

In general, the “fragile” regional press was “enduring itself throughout the dictatorship, but without standing up to it”, observes, in statements to Lusa, researcher and university professor João Figueira.

“The local and regional press was, generally speaking, a well-behaved sector during the Estado Novo”, he portrays, explaining it with “the absence of consistent business structures” and “excessive amateurism”.

The “irrelevance” of local and regional newspapers “as a field of resistance and combat against the dictatorship” does not, however, rule out some “emblematic cases of newspapers that fought against the current”, points out the professor of Journalism at the University of Coimbra.

This list comes to the top of the list – “Comércio do Funchal”, “Jornal do Fundão” and “Notícias da Amadora” –, which, according to the Hemeroteca Municipal de Lisboa, were the most read regional newspapers in the country.

These three newspapers “were created around ideas”, at a time when news didn't count and the press “was practically just opinion”, recalls João Palmeiro, media analyst and cultural producer.

“What counted were the locally important people (doctors, pharmacists, lawyers, judges) who wrote about what was happening locally”, he adds, remembering that the newspapers had no correspondents in Lisbon and “didn’t have the slightest idea” of what there it happened.

“The vision we have of opposition to the regime, ideologically and politically, we do not find in the regional press, what we often find is opposition to the central power, when it tries to do things that the local population does not want”, he highlights, in statements to Lusa.

In fact, the regional press “only got involved in matters of national order in two circumstances, if there were official visits or inaugurations by members of the government, or in so-called cases of local interest”.

João Palmeiro, who for decades represented the Portuguese Press Association, the most representative association of newspaper and magazine editors, gives as an example the “uproar” caused in the 1950s when Lisbon decided to regulate the houses of regions or municipalities.

Amadora, Funchal and Fundão were bastions of opposition to the dictatorship

The opposition of the regional press to the Estado Novo came mainly from three places, Amadora, Funchal and Fundão, whose respective newspapers left a mark on the dictatorship's path to democracy.

José Maria Amador joined the “opposition hostel” at the age of 18, which was “Comércio do Funchal”, published since September 1934.

The matrix of the weekly newspaper – which cost four escudos in Madeira and had as its director and owner, since 1967, João Carlos da Veiga Pestana – “was to be critical of the regime”, recalls the Madeiran native to Lusa, who did not continue in journalism, dedicating himself to the area of cultural heritage.

Amador remembers how the newspaper was made: “It was all manual. A dozen young people interleaved the pages and folded the newspapers and then took them to the post office, in packages transported in their own vehicles. It took one night.”

The “pink newspaper”, as it was known, had a circulation of around 15 thousand copies, two thirds of which went to the Continent, where it had “some influence, especially in university circles”, contributing to “awareness of a left-wing student elite”.

At the same time, the newspaper had a pioneering local section on what was happening in Madeira.

“Comércio do Funchal” was “a pagoda” where “all political currents critical of the regime at the time wrote, social democrats, socialists, MRPP's, Trotskyists, the more radical left, only the PCP was left out”, describes Amador .

The newspaper united in dictatorship what it was unable to combine in democracy, ending shortly after the 25th of April.

Being in Madeira was, initially, an advantage, as “there was greater liberalization and things went relatively easily with local censorship”, recalls Amador.

However, this only lasted until the regime realized that it had to tighten its grip: the newspaper began to be censored in Lisbon and was even suspended.

It would only resume activity when Marcelo Caetano was already in power, who returned “Comércio do Funchal” to local censorship, at the same time that Vicente Jorge Silva assumed himself as one of its main promoters.

“Jornal do Fundão” also had “a national dimension”, visible especially in Beira Interior, Lisbon and in Portuguese communities in the diaspora.

The cultural supplements, one of the weekly newspaper's trademark images, “have become a reference in the history of the Portuguese press”, highlights Fernando Paulouro.

“Portugal was a country closed in fear”, recalls the journalist, speaking to Lusa.

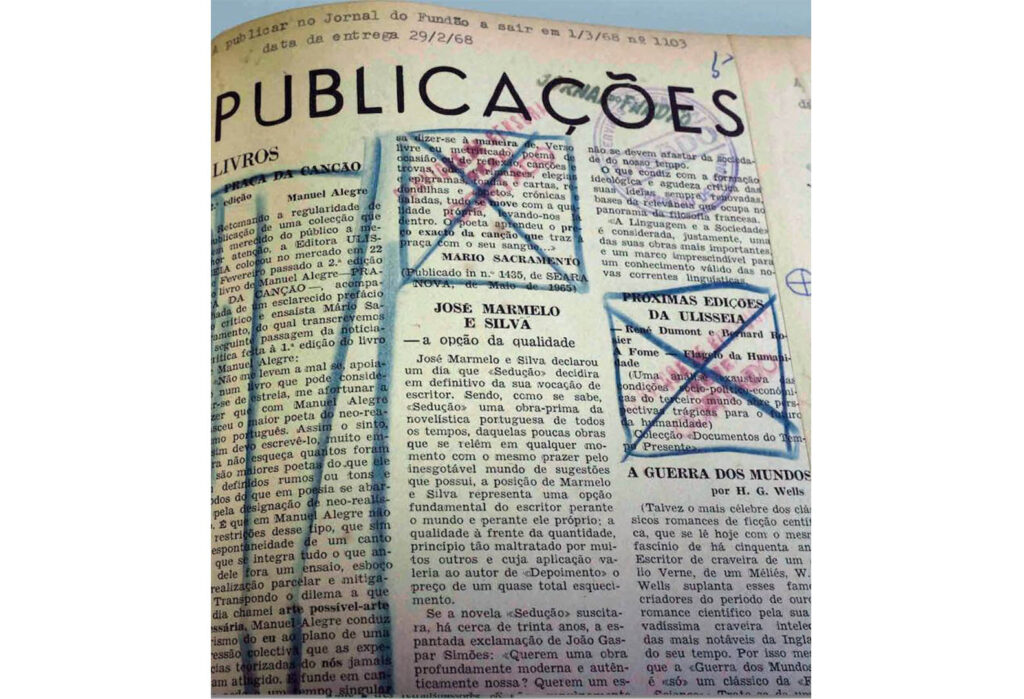

Founded by António Paulouro, in 1946, “Jornal do Fundão” was suspended for six months, in 1965, for having published the news of the awarding of the prize from the Portuguese Society of Writers to the Portuguese-Angolan writer Luandino Vieira.

Fernando Paulouro, who began to collaborate with the newspaper while still a student, reports that, from the 1960s onwards, the newspaper began to be targeted in page tests by the censorship in Lisbon, a “special regime” that the dictatorship preferred to hide.

The newspaper always said “targeted by Lisbon censorship”, the censorship always removed “from Lisbon”, he recalls.

“The censors turned newspaper readers into detectives of the word, waiting to see things there that weren't there but should be there”, describes Fernando Paulouro.

The “newspaper of causes and solidarity with people”, which cost three escudos, published its last issue two years after the 25th of April.

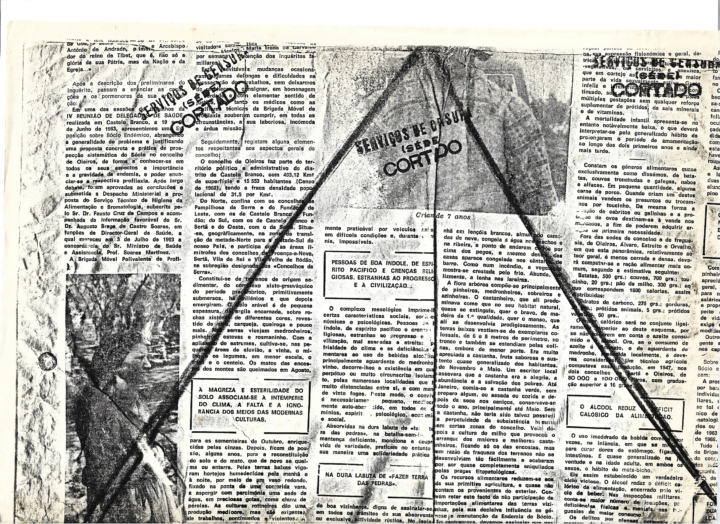

Censorship was particularly aggressive over “Notícias da Amadora”, mutilating 2.776 pieces between 1958 and 1974 and arresting its director, Orlando Gonçalves (1963-1994), several times.

Founded on October 25, 1958, it cost five escudos.

A few days before the 25th of April, the political police (PIDE-DGS) stormed the typography and newsroom of Notícias da Amadora, seizing material and arresting journalists.

One of the most influential periodicals opposing the Estado Novo, the “popular weekly” had a lot of influence among exiled opponents.

Son of Orlando Gonçalves, Orlando César, who would direct the newspaper from 1994 until its closure in 2006, reminded Lusa that “Notícias da Amadora” had “people from all over” and that it was this “diversity ” which gave “broadness to the newspaper”.

“Notícias da Amadora” entered the life of Orlando César when he was 13 years old, diverting him from agronomy to journalism.

During the dictatorship, from Angola, the journalist sent photos of massacres in indigenous communities and wrote regularly in the newspaper, mainly chronicles. Subject to several censorship cuts, he sometimes had to resort to pseudonyms.

After the 25th of April, Orlando César was “a kind of correspondent in Angola”, returning to Portugal in June 1975.

Comments