A little over 100 years ago, in 1918, bookstores saw the book «O Algarve Económico» by Tomás Cabreira reach their showcases.

The terrible pandemic that hit the world at that time, which Portugal, and the Algarve in particular, did not escape, and the author's own death in the midst of the Pneumonic crisis, on December 4, 1918, in Tavira, have taken away much of the shine. and the discussion that the work deserved.

Major figure in the region, born in Tavira, where he was born on January 23, 1865, military, republican, councilor of the Lisbon City Council in 1908, graduated in civil engineering, university professor, constituent deputy for Faro in 1911, senator and finance minister in 1914, Tomás Cabreira attained the degree of doctor in 1916, and the rank of colonel in 1918.

Author of multifaceted works, he constituted the greatest soul of the I Algarve Regional Congress (1915), which we have already mentioned here.

A convinced regionalist, he always defended the Algarve, as was evident in the last sentences of the conclusion of the book that we propose to remember here: «the future and aggrandizement of the Algarve are in the hands of the children of this blessed land and for it to be rich and prosperous this book was written by one of the humblest people in the Algarve but also one of the most fanatical about his homeland».

But does it make sense to remember today a work that is already a century old? An Algarve that has long since disappeared, under the weight of years and successive generations?

In fact, we almost dare to say that the book «O Algarve Económico», published 103 years ago, is today as current as it was then and we can only regret that it is so difficult to find, as it has been around for a long time. exhausted and unjustly doomed to oblivion, despite being present in most libraries in the region.

Profoundly documented, the work was intended to demonstrate that the Algarve had all the conditions to enjoy complete administrative autonomy, as was the case then with the districts of Madeira and the Azores.

Well, dear reader, autonomy for the region, where have we heard this?

Tomás Cabreira does not limit himself to outlining the regional economy, he points out the constraints and lists the potential that it contained. In short, a diagnosis is made, solutions are identified and long-term paths are traced.

Today, when a new pandemic threw the Algarve into a health, economic and social crisis, his book, «one of the most remarkable works that has been devoted» to the region, in the words of Mário Lyster Franco (1902-1984), has the ability to remind us and compel us to think that tourism, which was then seen as an opportunity to seize, became a reality only a little over 50 years ago and the region's economy was already thriving in 1918.

It is true that climate change today metamorphoses with unpredictable consequences, but still many of the potential and advice listed then are current.

Divided into 17 chapters, divided between topography and climate to finance, the region is studied in all its aspects and economic modalities, over almost 300 pages, accompanied by tables and statistical tables with comparisons between the Algarve councils, districts country and not rarely with different countries in Europe or even the United States of America.

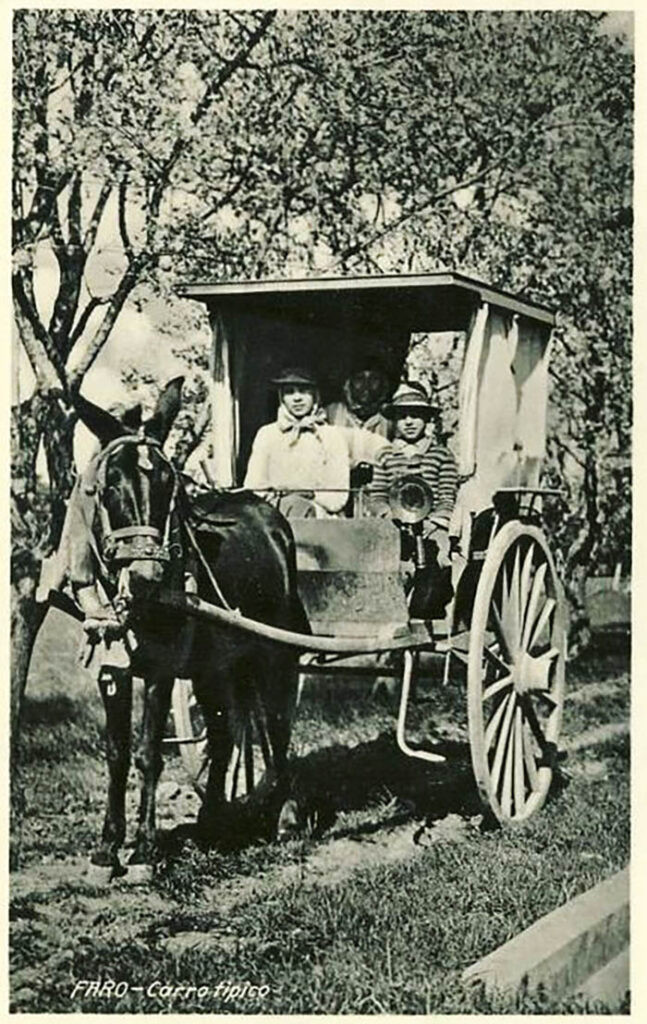

Export markets are pointed out, but also the movement in all postal stations in the Algarve, between 1905 and 14 (incoming/outgoing correspondence, telegrams, parcels), in railway stations (passengers and goods, embarked and disembarked), transport (roads, horsepower, vehicles and automobiles in each county; for example, there were only 4 automobiles in 1912), the number of boats entering the ports and respective tonnage, as well as the existing ones.

In short, a wealth of information that allows us to get to know the reality of those times with rigor. So let us take a very brief journey through its pages.

In chapter I, the similarities of the climate with the Côte d' Azur, the Riviera and the Malaga area are pointed out. In II and III, the population, its evolution in the parishes and specificities (birth, mortality, nuptial rates, demographic and social characteristics) are studied.

Subsequently, he focuses on the rustic property, remembering "that the Algarve is essentially hardworking and economic", comparing the number of rustic buildings, taxpayers and taxable income per municipality, the proportion of different crops in the cultivated area, without forgetting that water is the «vital question for the Algarve».

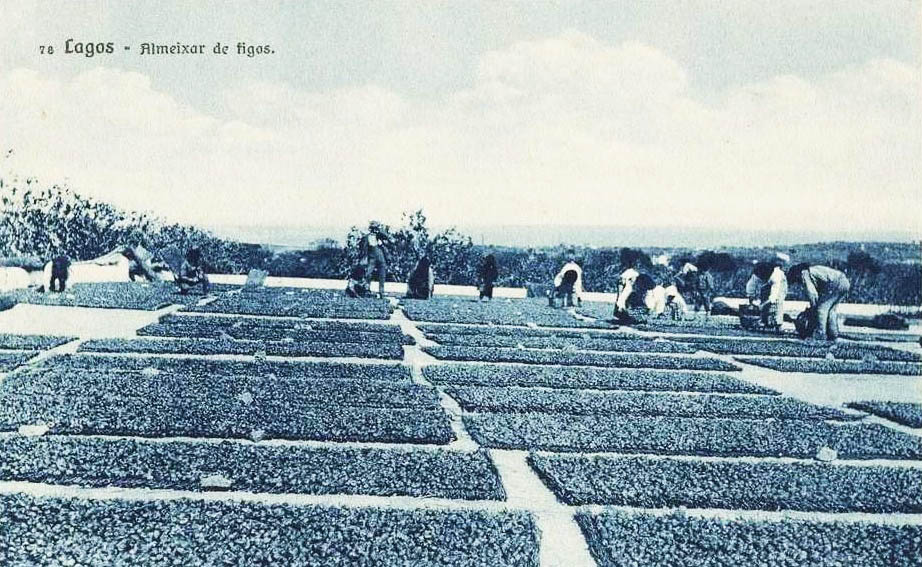

It recalls the predominance of fruit trees and horticultural crops (the products are 15 days ahead of those in other regions) and arable crops, followed by vines, cork oaks and forests.

He advised the association of farmers, as most of them were small landowners with few resources, as well as the installation of agrarian posts, for the constant updating of techniques.

In «watered crops», in chapter V, he emphasizes the «sweetness and exquisite taste» of the fruits of the Algarve, oranges and tangerines, apricots and peaches, with their aroma and magnificent taste, the pomegranates or loquats from Japan , large.

Noting that, in the east, the products are more early, so it was opportune to cultivate prime vegetables and orchards for export to the English market and northern Europe.

It indicated the culture of table grapes (with two types, early and late, as well as raisin) and floriculture (carnations, roses, anemone, hyacinth, daffodil and lilies, as well as those intended for the extraction of essences, such as lavender, etc.) then non-existent in the region.

In a kind of synthesis, he referred that, «when studying the attempt or expansion of any culture in the Algarve: for a given capital, employed in land, water and labor, the culture that is going to be tried or expanded, will give an income bigger than any other culture? If so, the culture must take place; if not, the most remunerative must be sought».

Therefore, he defended the abandonment of cotton cultivation, which had been tried with some success during those years, and the bet on pineapple.

Chapter VI was devoted to "almond trees, fig trees, carob trees, olive trees and groves". Of all, the almond, fig and carob trees stood out as the most economically important, whether or not they were the traditional dryland orchard in the Algarve, the economic engine of the region, since long ago, especially figs. Therefore, proposing its most productive culture, care and varieties.

He considered that, despite the «absolute lack of technical education and the systematic contempt that the public authorities have for the most beautiful region of Portugal, the Algarve farmer, with charismatic captains, performs true miracles, which make the Algarve coastline a veritable garden» . A contempt that the weight of the years has not yet dampened and that is perpetuated.

He also noted potential for the olive tree: «the Algarve has all the agrological conditions to provide one of the best types of national olive oil».

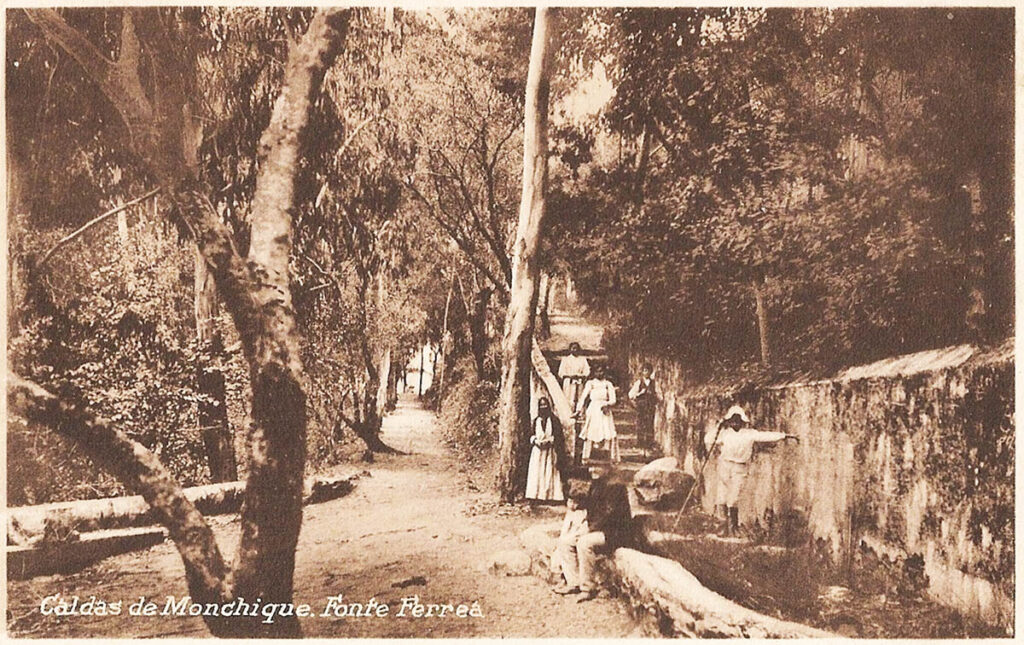

Finally, he pointed out the importance of the chestnut trees in Monchique, either for the fruit or for the wood, which was in decline caused by a plague and the indispensability of «energetically defending the chestnut trees that escaped the disease, preventing, by all means, that they are destroyed by other causes'.

The cork oak forests, forests, vines, cereals and vegetables occupied the entire chapter VII. The little afforestation in the region, with the exception of the coast, led Tomás Cabreira to urgently propose the afforestation of the entire Algarve mountain range, as a way to regulate the flow in the streams (torrential in winter and drought in summer).

Proposing for this purpose two essential groups, more remunerative (in terms of good wood for civil and naval construction), one consisting of indigenous trees, pine, holm oak, cork oak, chestnut and carob, and another with exotic species such as eucalyptus.

We remind the reader that we are in 1918 and that the afforestation of the mountains with endemic species is still the order of the day, while the unruly planting of eucalyptus turned the entire mountain range into a powder keg…

As for the vineyards, it reported that the district of Faro it was one of those with the highest wine production per hectare, presenting its composition in the different municipalities and noting the feasibility of producing fortified wines.

In cereals, wheat (of which the Algarve has always been in deficit), maize, barley, oats, rye and rice were studied, while in vegetables, peanuts were not forgotten.

In turn, marshes and livestock appear in Chapter VIII. Cabreira defended the use of marshes for the production of fodder, for example, and as for livestock, cattle, swine, sheep and goats had primacy. Horse cattle, on the other hand, were scarce, only in Castro Marim there was a small nucleus of equestrian breeding. The mule was of superior importance, although the highlight was for the donkey. Other times when technology was not being felt.

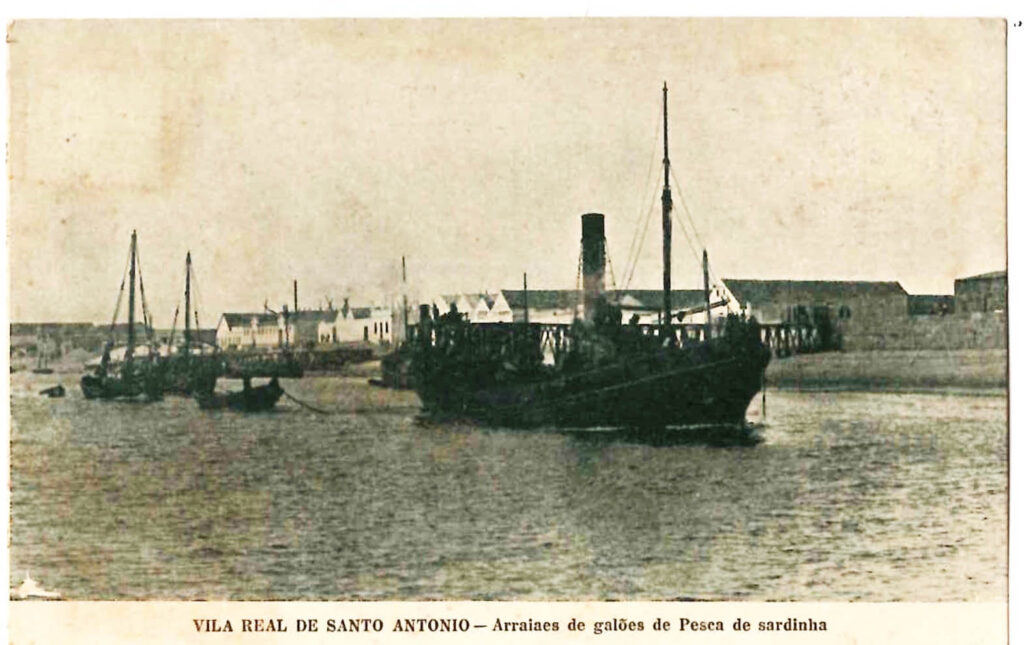

In chapter IX, “fishing and salt pans” were analyzed. Two activities that are also historic in the regional economy. Sardines constituted then the greatest wealth of fish resources, with 57,4%, followed by tuna, with 20,5%. The fishing of this fish was already practiced in Antiquity, existing in 1914, between Sagres and Tavira, 13 traps that employed about 1500 men.

It proposed the introduction of fish farming and the cultivation of oysters, due to their “very fine palate, far superior to all those sold in Paris”, for export to France.

The industries are listed in chapter X, highlighting the extractive, mineral waters, shipbuilding, canning (remembering that the canning of sardines was started in the region in 1880 by the French).

In 1907, there were 33 canning factories in the Algarve, with 3100 workers, constituting in 1918 the most important industry in the district, with more than 100 factories.

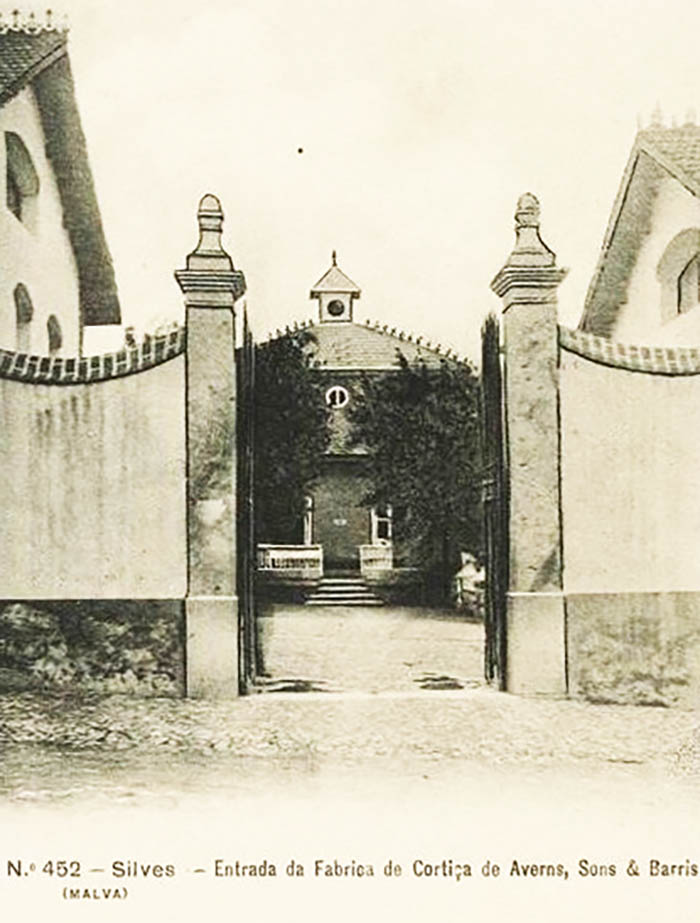

Similarly, the cork industry was also evident, albeit in crisis, with 20 factories in 1911.

About civil construction, he warned about the high seismicity and the convenience of using the Pombaline cage in all buildings.

In small industries, he listed bodywork, palm articles, esparto, shipbuilding, sweets, etc., etc.

Transport was studied in Chapter XI, and commerce in the immediate part. In the latter, items imported and destined for export are indicated, their quantities and countries of destination, the main precautions in packaging, in short, an authentic marketing action, presenting the region with a favorable trade balance.

Commerce also occupies the next two chapters, the XIII - "commerce with England" and the XIV - "commerce with other countries". There the quantities and exported products are listed, as well as the amounts involved, comparison with other countries and new business niches for endogenous products are indicated.

The third-to-last chapter was devoted to the establishment of new industries "likely to establish themselves in the Algarve". It is a true treaty of activities that can be successful, around the agricultural, agricultural, maritime and manufacturing industries. A synthesis of the hypotheses raised throughout the book, from floriculture, caper farming, pita fig, tubers, poultry and rabbit farming, beekeeping, fish farming, oyster farming, perfumes, canned olives and tomatoes, among others.

In the penultimate chapter, "tourism and sanatoriums" appears. The tourism industry, which materialized after the 1960s, and as such we will not address it, despite the author's notes and warnings remain so present.

Finances complete the work. Through the analysis of the last chapter, Tomás Cabreira had no hesitation in stating that the Algarve paid much more to the State than it received, so the conclusion could not be different, that the region could and should enjoy autonomy: «count on its own resources to have a longer and more intense life».

His death, still in 1918, the aggravation of political, social and economic instability, resulting from the end of World War I and the pandemic, led to the advent of the dictatorial, centralist regime, preventing and delaying the autonomy of the region, until today , although in the early 1920s the independence of the Algarve was aired in the regional press.

The work, according to what has been stated, despite having been published over 100 years ago, maintains a topicality as haunting as it is surprising in the most diverse aspects.

After all, the publication date of a book does not always make it an outdated work and Tomás Cabreira deserves this tribute, for the fruitful learning he offers us, through the complete reading of his masterful work.

Once again we are going through a very troubled period, but his last words also contain a timeless perennity: «the future and growth of the Algarve are in the hands of the children of this blessed land», so let us rise to the challenges that lie ahead.

Author Aurélio Nuno Cabrita is an environmental engineer and researcher of local and regional history, as well as a regular collaborator of the Sul Informação.

Note: The images used are for illustrative purposes only and correspond to illustrated postcards. In the transcripts, the spelling of the time was maintained.

Comments