The delay with which modern science – inaugurated by great names of the Scientific Revolution such as Copernicus, Galileo, Descartes and Newton – arrived in Portugal can be illustrated by the notice posted on the door of the Colégio das Artes, in Coimbra, in 1746, signed by the rector of that Jesuit school: “in exams, lessons, public or private conclusions, new opinions that are little received or useless for the study of major sciences such as those of Renato Descartes, Gassendi, Newton and others, namely, any science that defends the atoms of Epicurus, or deny the reality of Eucharistic accidents, or any other conclusions contrary to Aristotle's system, which in these schools must be followed”.

This is just one of the pieces of a conflict, which became famous, between the Ancients, the followers of Aristotle, and the Moderns, the followers of the scientific method, based on observation, experience and mathematical reason, which marks the so-called Revolution.

In the middle of the XNUMXth century, when the French Descartes and Gassendi, the two contemporaries of Galileo, and the Englishman Newton, of the next generation, had long since passed away, their ideas remained closed between us.

It was useless for Gassendi to be a Catholic priest, since he had dared to recover the atomistic ideas of the Greeks, which, for official theology, clashed with the faith.

Church dominance did not help. O Index of Prohibited Books, which appeared among us in 1551, even before its Roman equivalent, banished Copernicus, Galileo and Descartes (and only on March 31, 1821, 200 years ago, the Inquisition, which ensured the application of the Index, was extinguished!).

The persistence of the reaction to Copernicus's heliocentric system, unsuccessfully defended by Galileo in 1633 in the Inquisition of Rome, is also indicative of the national backwardness. In 1753, in a work by an anonymous author (probably a Benedictine priest), it is said: “If it is the same to oppose the Faith as to be false, how are they not ashamed to say that in Copernicus' system the phenomena of nature?".

For the triumph of the Moderns, the works were decisive for Rational, True and Analytical Logic (1754), by Manuel de Azevedo Fortes, and the True Method of Studying (1756), by Luís António Verney (reprinted in Pioneiras da Cultura Portuguesa, Círculo de Leitores, 2018). Both are inspired by Descartes.

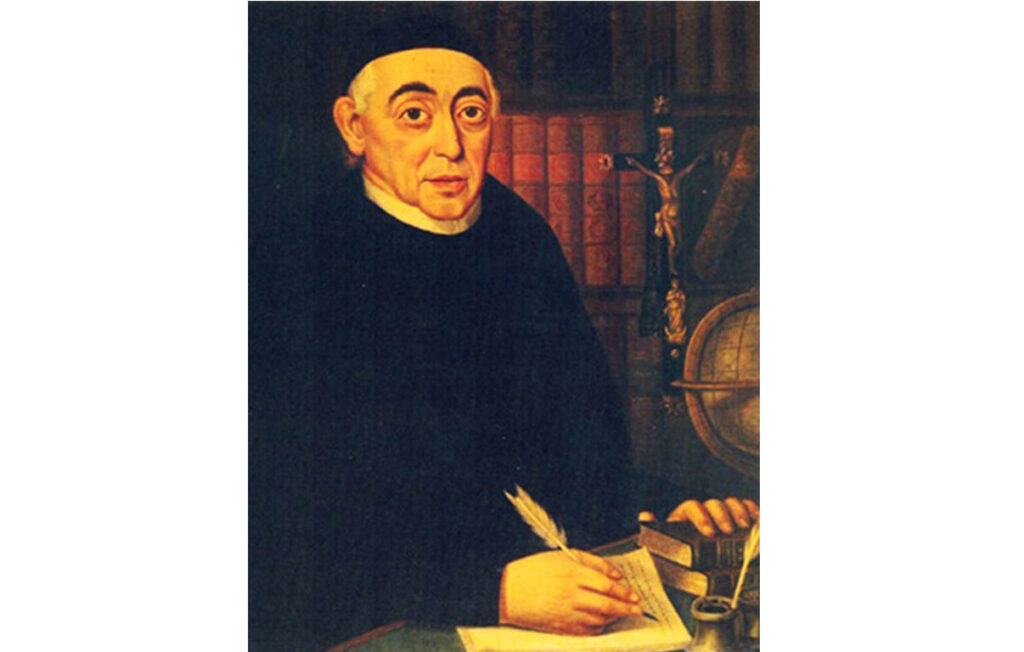

It was the Oratorians, the Order founded in 1565 by Filipe Néri, who, in Portugal, gave the most impetus to modern science. In his college – where the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is now located –, in 1751 Physics classes were given with experimental demonstrations, which King José attended. Long before 1772, when the Pombaline Reform of the University of Coimbra instituted experimental science teaching in the then only Portuguese university.

It was also in 1751 that the first two volumes of the Philosophical Recreation, by the oratorian Teodoro de Almeida. This first treatise on Physics in Portuguese (reprinted in the aforementioned Obras Pioneiras, 2017) already follows a markedly modern orientation.

The Lisbon Academy of Sciences only appeared in 1779, more than a century after its British counterpart, the Royal Society of London, to which Teodoro de Almeida belonged. It was this author who, after a decade of exile in Spain and France due to the closing by the Marquis of Pombal of the Oratorian College, made the first prayer of wisdom in the new academy, in which he equated Portugal with Morocco, giving rise to protests by the marquis's followers.

It is unfair, as the Pombaline propaganda machine did, to accuse the Jesuits of being extremely backward. Some of them gave great examples of modernity. It was the Italian Jesuits Paolo Lembo and Christophoro Borri who brought Galileo's telescope to Portugal, less than four years after it was first used in Italy, in 1609. And it was from here that it went to the Orient.

The Aula da Esfera, which operated at the Jesuit College of Santo Antão, where the Hospital de S. José is today, was a fertile international school of Mathematics from its foundation in 1590 until its inglorious closure by the Marquis in 1759.

The Jesuit Manuel Dias, in 1615, was the first to mention Galileo's discoveries in China, in his Mandarin book Summary of Celestial Matters. The Scientific Revolution entered China by Portuguese hand!

But an even more important note is necessary: the Scientific Revolution would not have been possible without the Portuguese Discoveries, which valued experience as the “mother of things”.

In fact, the foundations of the scientific method are already found in the work of sixteenth-century Portuguese scholars, such as doctors Amato Lusitano and Garcia de Orta, the mathematician Pedro Nunes, and the geophysicist D. João de Castro. They were, therefore, pioneers of modern science. Delay? No, in these cases there was an advance...

Author Carlos Fiolhais is Professor of Physics at the University of Coimbra

Comments