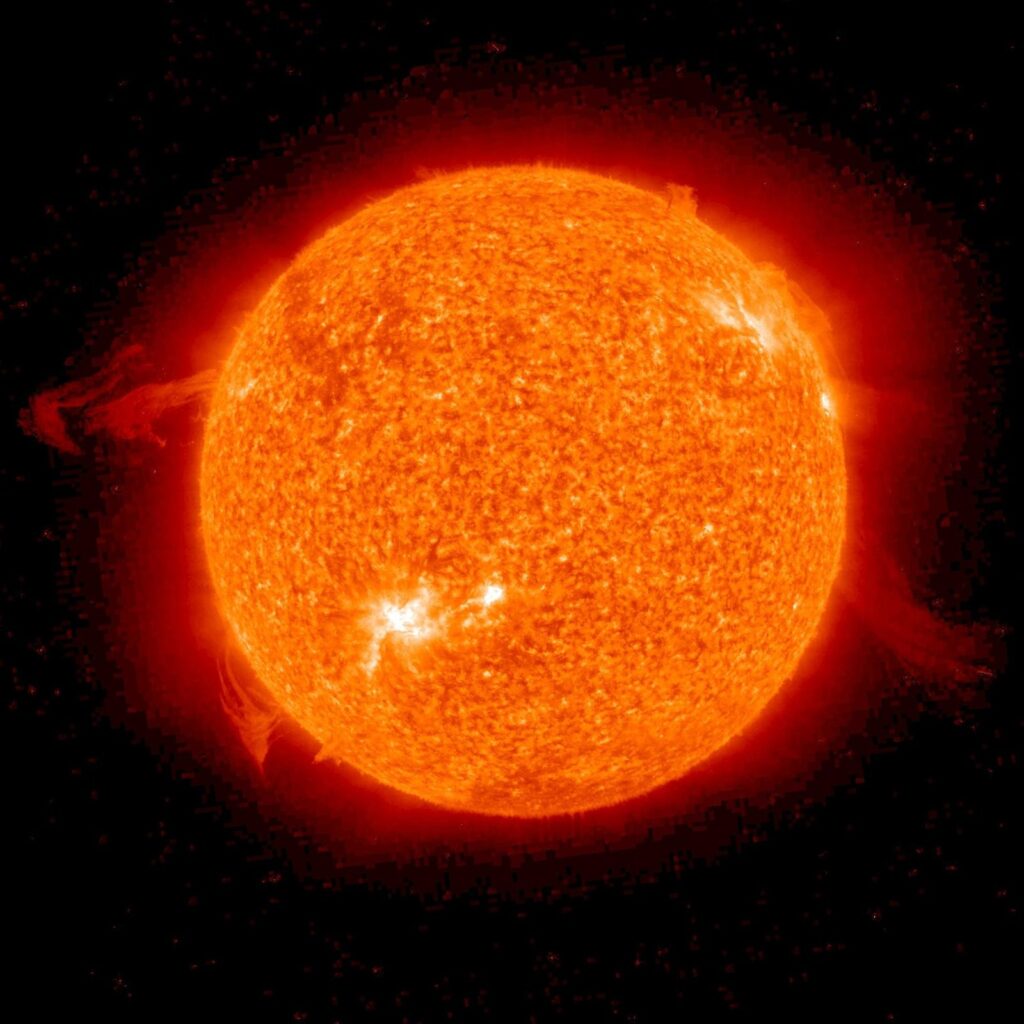

The Sun is a star. For us inhabitants of Earth, it is the most important star. The Sun is very hot (6000 degrees at its surface) and has a diameter 100 times larger than Earth's.

However, the distance that separates us from the star-king, about 150 million kilometers (a value that astronomy calls “astronomical unit”), provides a cosmic cohabitation that has allowed life and its evolution in this small blue dot in space , which is to our planet.

But the Sun, being unique to us, is just one of the 100 billion stars that will exist in our galaxy, the Milky Way. Of this colossal number, more than half of the stars belong to binary systems: stars that rotate around each other in a stellar ballet driven by mutual gravitational attraction.

All this the reader will already know. What is perhaps less well known is the idea that the Sun may also have belonged to a binary system. There is no doubt that the Sun today does not have the company of another star.

But it may not have always been like this. Less than a year ago, researchers Amir Siraj and Abraham Loeb, from Harvard University, Cambridge, in the United States of America, in a five-page scientific article, defended the theory that the Sun in its formation (ie, there are about 5 billion years) may have had a companion star, of equal mass, at a distance of about 1500 astronomical units.

In terms of comparison, say that Neptune – the most distant of the planets in the solar system – is a “few” 30 astronomical units from the Sun. This so great distance could explain why this supposed star is no longer finds among us today, reduced as it was to such mutual gravitational attraction. Far from sight, far from the heart!

But why did these researchers bother to support such a peculiar theory? Motivation is common in science: trying to solve an open problem. In this case, it is the origin of the Öpik-Oort cloud, a huge agglomeration of small bodies that are distributed in an approximately spherical shape, around the Sun, at a distance of more than 10 astronomical units.

This cloud, made up of distant pebbles, is the cradle of comets with orbits dating back thousands of years, and its name honors two distinguished XNUMXth-century astronomers who spoke about it: the Estonian Ernst Öpik and the Dutchman Jan Oort. Well, astronomers have been struggling for many years to explain how this cloud formed.

According to Siraj and Loeb, the existence of a second star in the solar system could help explain it. The argument behind this idea is simple: another star “placed” at the right distance would have allowed the cloud of thousands of small bodies to be maintained and concentrated, something that a single star – the Sun – would have difficulty doing.

On the other hand, this help would not have been for very long: researchers estimate that the solar companion was around for “only” 100 million years and was later ejected. Yes, for the avoidance of doubt: at present there are no other stars in the solar system other than the Sun.

If there were a star like the Sun at “only” 1500 astronomical units, it would have been known since antiquity. And so a new star is “invented” to solve an old problem. In short, for things we see that are inexplicable, we use good explanations based on things we don't see.

Is the reader confused? I understand, but I can assure you that it is a technique used in astronomy more often than you think and has given good results over time. And because we have already talked about it, let us remember that the discovery of Neptune was due to the mathematical predictions of the Frenchman Urbain Le Verrier, in 1846, who, knowing about the anomalous perturbations in the orbit of Uranus, postulated that there must be an as-yet-unknown planet interfering with the movement Uranian. And he was right.

The German Johann Galle, from the Berlin Observatory, that same year and motivated by these reflections, discovered Neptune. Out of curiosity, we added that something that works once may not work the next time: in the face of reported anomalies, now, in Mercury's orbit, the same Le Verrier, in 1859, would predict the existence of a new planet with an even more orbit close to the Sun. It was even named: Vulcan.

It has been looked for, but no one has ever seen it because, in reality, it is not there. These anomalies would only be explained using Albert Einstein's Theory of General Relativity, at the beginning of the XNUMXth century.

Let's return to the supposed companion star of the Sun. Now what? As scientific as it is, theory will have to make its way constantly confronting itself with new ideas and discoveries, resisting (or not) the healthy contradictory imposed by science and nature.

In other words, in a few years we may be here writing that this theory, about an ephemeral solar companion, has been consolidated and is part of our children's schoolbooks, or even that it was refuted in the face of new evidence and will not pass of a paragraph in any review of the history of astronomy in the XNUMXst century. It's science at work…

Author João Fernandes, astronomer, FCTUC.

João Fernandes was born in Arcos de Valdevez and is Assistant Professor at the Mathematics Department of the Faculty of Science and Technology of the University of Coimbra since 1999.

He obtained a PhD in Astrophysics and Space Techniques from the University of Paris VII (in 1996) and since then he has made the stars his main research area.

Comments