Everyone has a plan until they are hit.

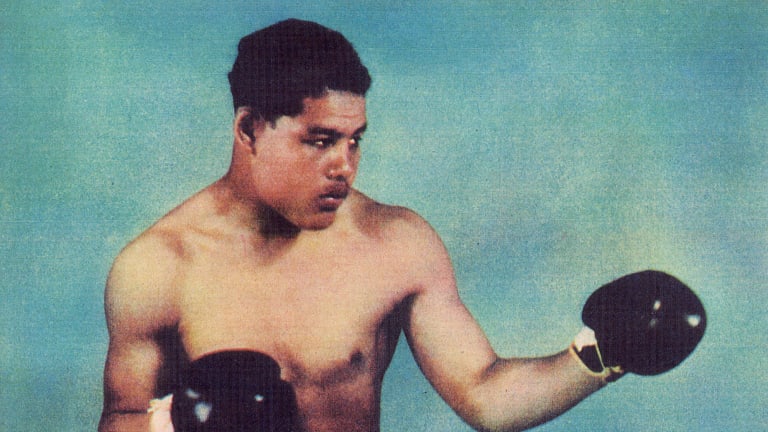

Joe Louis, Boxer, 1914-1981

The pandemic revealed, with terrifying cruelty, the inconsistencies of contemporary society and how it rests on largely unsustainable foundations.

Globalization, which has brought benefits to many, has also left a trail of destruction in many other places, by transforming itself, especially in the last 30 years, into a process far removed from the real economy, financialized, uprooted from territories and increasingly susceptible to crises recurrent.

Two key aspects have become relatively evident with the spread of the Covid-19 outbreak and forced confinement in most countries in Europe and the world.

The first underlines how the narrowing of the functions of the State, with the privatization of essential services for collective life – as was the case with Health – limited the capacity to respond to the health crisis.

The second is related to the progressive disappearance of industrial productive capacity in many countries – particularly in goods that proved essential in the critical phase of the outbreaks, such as masks or fans – relying on global trade flows, mainly from China.

These two aspects limited the resilience of the economies of different countries and regions to the short-term crisis generated by Covid-19.

Deepening the discussion on economic resilience requires two considerations. The first is that it is a characteristic of complex adaptive systems. This means that, although the mechanisms are not yet clear, there is a relationship between resilience at different levels.

The resilience of a country is not independent of the resilience of its regions, communities, the resilience of organizations and individuals. And vice versa. It is, therefore, essential to think and act on different planes.

The second consideration is that resilience is a dynamic phenomenon. What can be understood as a sign of resilience and rapid recovery may ultimately not have the support to sustain itself for a long time and create serious weaknesses for the next crisis.

In other words, the recovery of the economy, in terms of output and employment, may even be accelerated (if a definitive solution to the pandemic itself is found – which remains to be done) but it will not solve the systemic problem of contemporary society nor the structural weaknesses of the Portuguese economy in the long run.

The most common understanding of resilience refers to the ability of a system to maintain its structure in the face of external shocks and disturbances (resistance – withstand the blow that Joe Louis mentioned, without flinching) or the ability to recover (taking the punch, staggering or even go to the mat, but get up quickly). But it's more than that.

The two previous strands of resilience are essential for the bouncing back, the return to “normality”.

But resilience must also be understood as the ability to adapt, to take the punch and present new responses based on existing structure and capabilities (reorientation, which is essentially changing tactics).

Or the generation of new ways to change the structure itself (renewal, which is the profound change in strategy and capabilities).

These transformative strands of resilience are crucial when you don't want to go back to the previous “normal” – because that “normal” is itself part of the problem. They are the sources for a leap forward, the bouncing forward, the creation of a “new normal”.

I therefore admit that it is relatively consensual that overcoming the economic crisis in Portugal (and in the Algarve – a particularly extreme case of concentration of economic activity in a fragile and exposed sector, tourism) depends on a structural change. We shouldn't want to go back to the past. Stop before the pandemic. We need a new future.

But this is not easy to achieve. Attempts at structural change in the economy are not simple. There are many path dependencies, many ties to the past, to instituted powers that limit the real possibilities for renewal.

In theory, the structural change of an economy can be based on four types of bets. The first, modernization, essentially refers to the incorporation of transversal technologies, such as information technologies or new forms of energy, into dominant sectors.

Second, diversification suggests the strengthening of a wide range of economic activities, reducing dependence on each one of them. Third, the transition suggests the need to transfer resources and knowledge from declining sectors to related ones, but with greater growth potential.

Finally, eventually more difficult to achieve is the radical foundation, the creation of a new, fast-growing area based on resources – in particular S&T – existing in the region.

In practice, selecting a new path is very complex. A strategy involves choices, it has to be selective because the resources are not infinite. To bet on an economic activity is to abandon a myriad of many others. Which are or could be important.

So it takes wisdom – not just information or knowledge – to select the right priorities. The path chosen must be transformative, which will also certainly imply a paradigm shift in the role of the State.

This can and must be innovative and must take risks, not only as a space for institutional, market and society regulation, or with Keynesian policies in response to crises, but as the main animator and financier of the development and implementation of innovations based on cooperation to solve the great societal challenges, such as the pandemics to come, the next financial crisis that is coming, or the climate emergency that has not disappeared.

We've already been hit. The punch still throbs in the face. It's time we got a real plan and put it into action.

Author Hugo Pinto

Economist; Researcher and Coordinator of NECES – Center for Studies in Economics, Science and Society of the Center for Social Studies, University of Coimbra; Visiting Professor at the Faculty of Economics, University of Algarve; European Commission Specialist

Note 1: The content of this article does not necessarily reflect the position of the Center for Social Studies, the Faculty of Economics or the European Commission. The opinion expressed is the sole responsibility of the author.

Note 2: article published under the protocol between the Sul Informação and the Algarve Delegation of the Order of Economists

Comments