Talking about the ways of Art in Portugal during the long and dark 48-year period of the fascist dictatorship, overthrown by the captains of April in 1974, requires that, in the first place, an understanding of the characteristics of this oppressive regime.

Very synthetically: a military coup, on May 28, 1926, supported by the most reactionary forces, established a Government of Military Dictatorship, which quickly evolved into a Fascist Dictatorship, with the dissolution of Parliament, the prohibition of all political parties, the creation of a Censorship on newspapers, books and all means of communication, the establishment of a fierce political police against all opponents of the regime and the purification of the military apparatus, with expulsion and arrests of soldiers loyal to the republican regime. These are the pillars of the new regime.

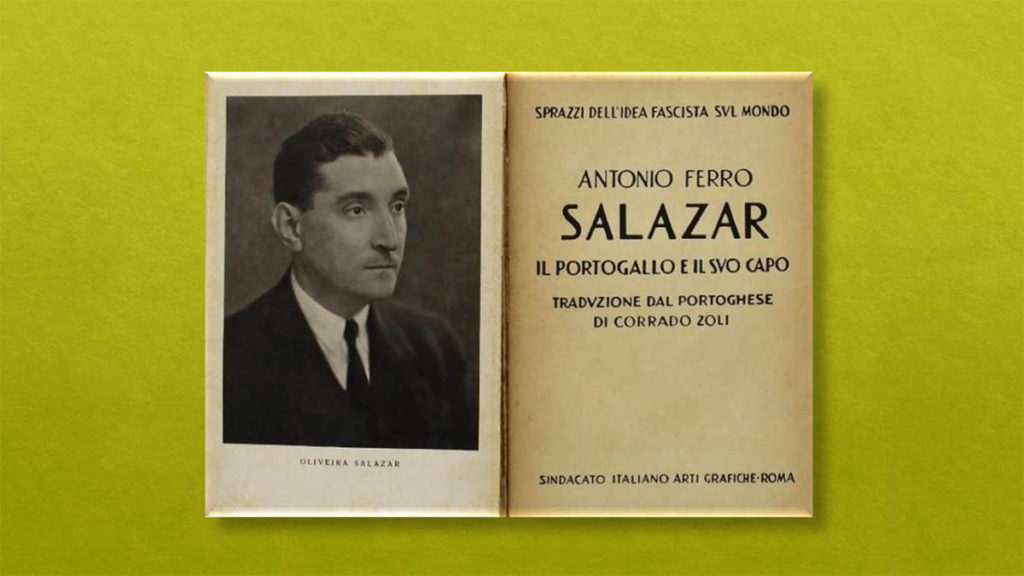

Oliveira Salazar became head of the Government in 1932, only after the conditions to liquidate all those who could oppose him were guaranteed. Salazar was linked to and had the support of the fascist regimes of Mussolini, established in Italy since 1922, and of Hitler, who had just been appointed Chancellor in 1932. They were the models followed by Salazar, in the political and propaganda fields.

It was following these examples that Salazar created, in 1933, the Secretariat for National Propaganda (SPN), to which he appointed António Ferro, an intellectual who had been in charge of the magazine in 1927. orpheus of the Portuguese modernists and who later published great praise about the Mussolini and Hitler regimes in the book “Viagens around two dictatorships”, and wrote a biography glorifying Salazar, edited in Italy, which guaranteed his appointment and trust. , to direct the so-called “politics of the spirit”: the dictator's designation of his policy of capturing intellectuals, subordinated to the regime's objectives.

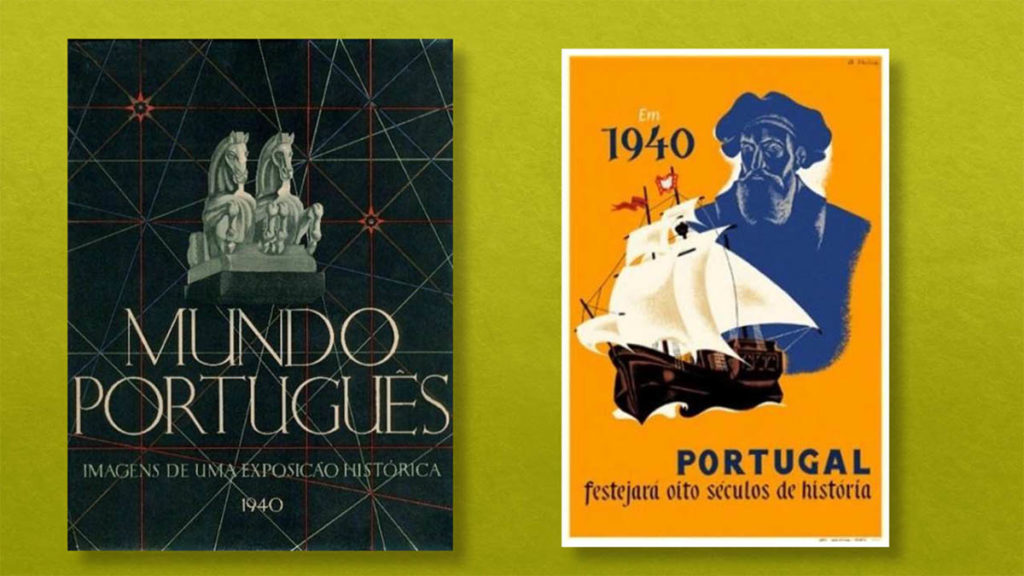

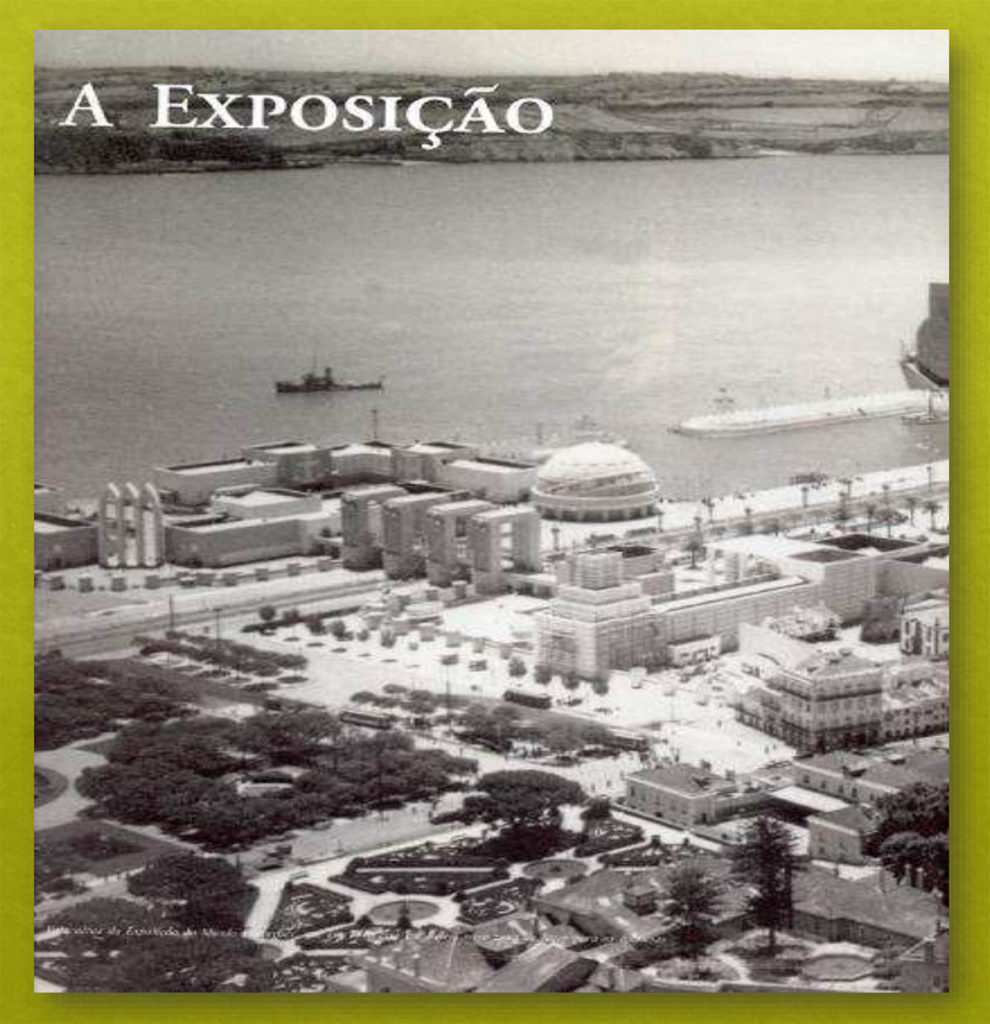

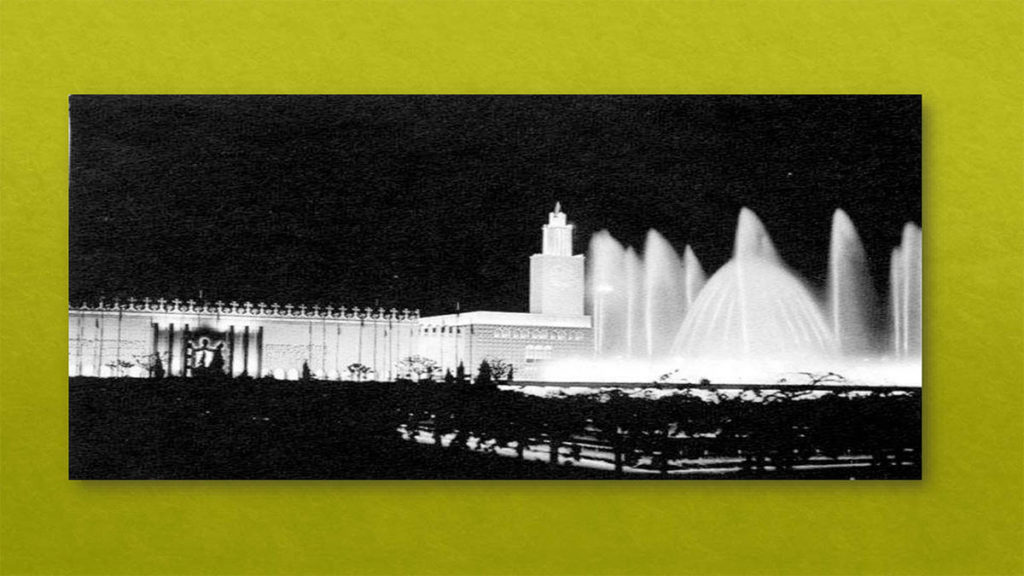

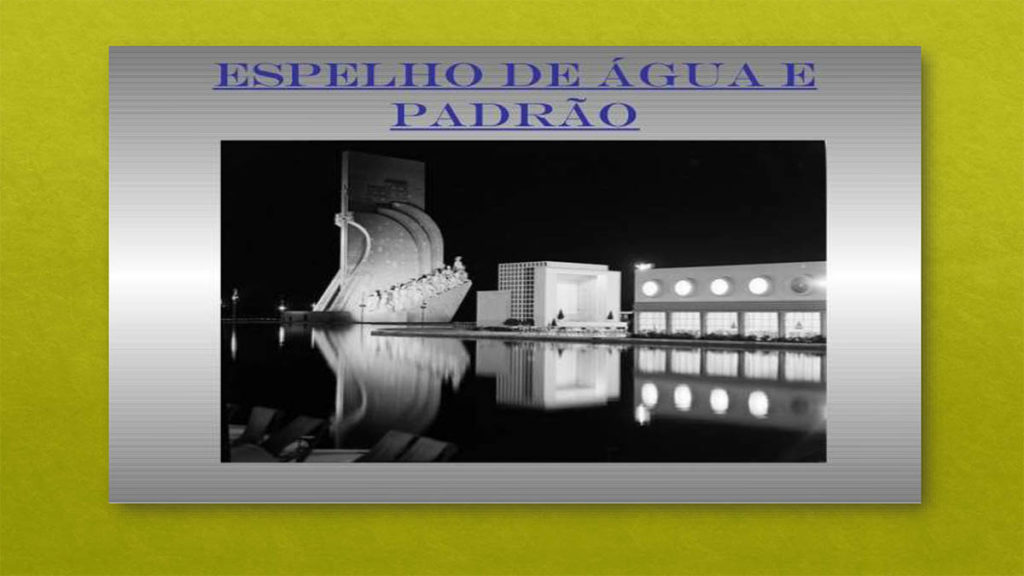

The culminating moment of this work of political propaganda came in 1940, with the inauguration of the Portuguese World Exhibition, linked to a set of Public Works under the supervision of the engineer Duarte Pacheco, and, in the artistic and propagandistic sphere, under the direction of António Ferro.

Salazar proclaimed the grandiosity of the regime, stating that "this year of 1940 would be perpetuated in the fold of time and in the imagination of those to come."

The symbolic magnificence of the Belém Exhibition had the attraction of numerous architects and plastic artists, particularly supporters of the regime, such as Pardal Monteiro, author of the maritime stations in Lisbon, Veloso Reis, of the Museum of Popular Art, who still remains the architect Cottinelli Telmo and the sculptor Leopoldo de Almeida, responsible, among other works, for the Padrão dos Descobrimentos, which stands by the river.

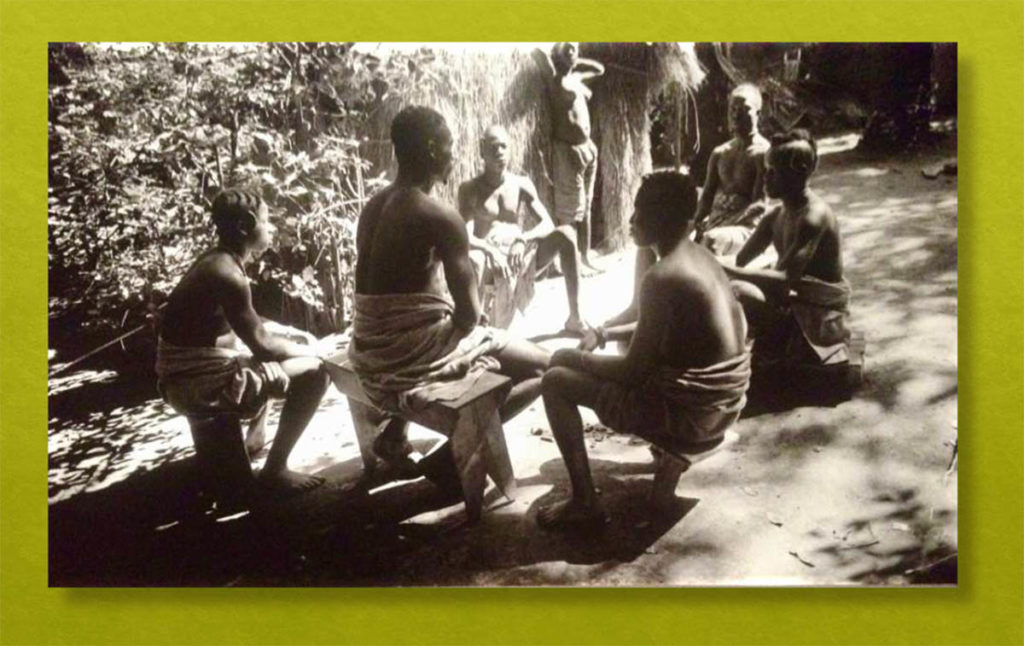

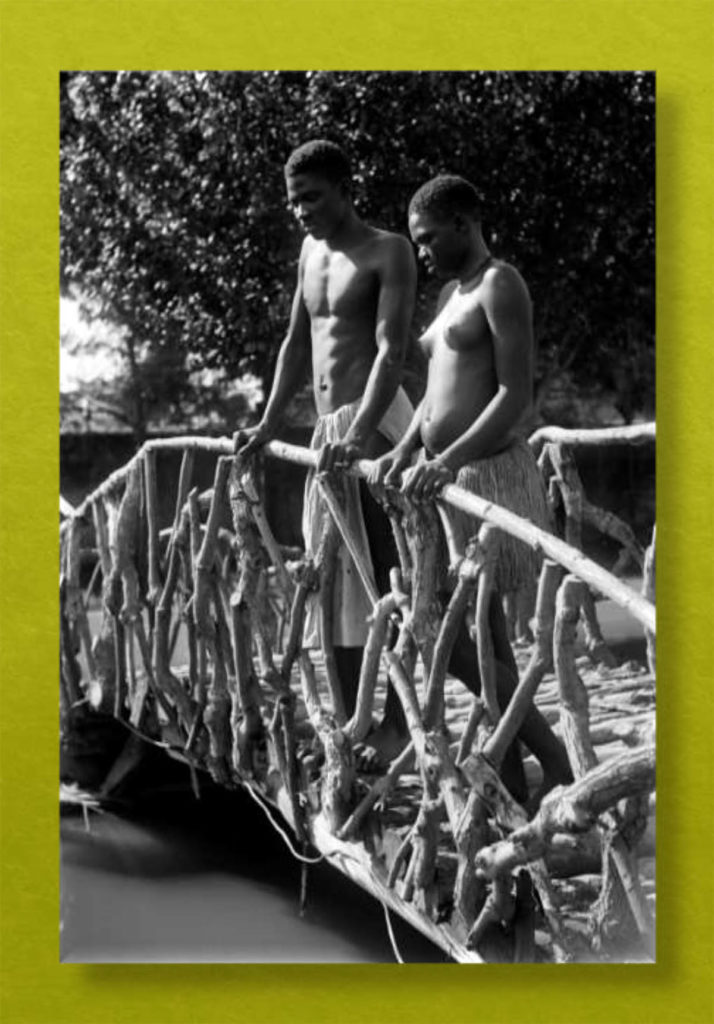

In the Exhibition, the Portuguese Colonial Empire was glorified, with African villages rebuilt and inhabited by the peoples of the colonies, exhibited there like animals in a Zoo.

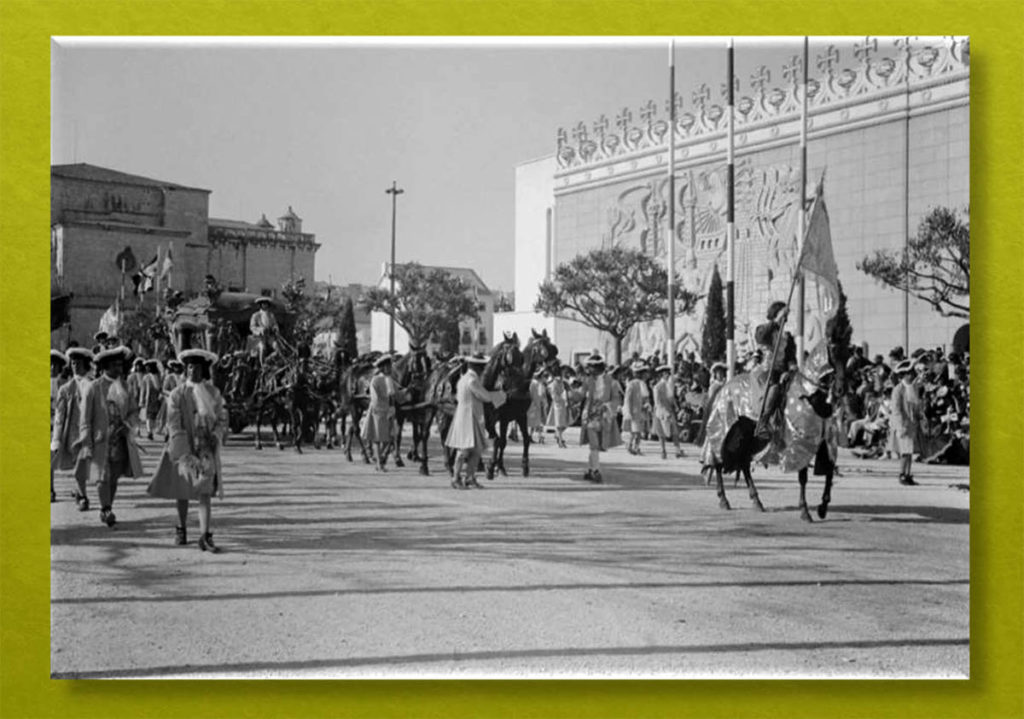

During the Exhibition, grand and sumptuous historical parades were staged by Leitão de Barros.

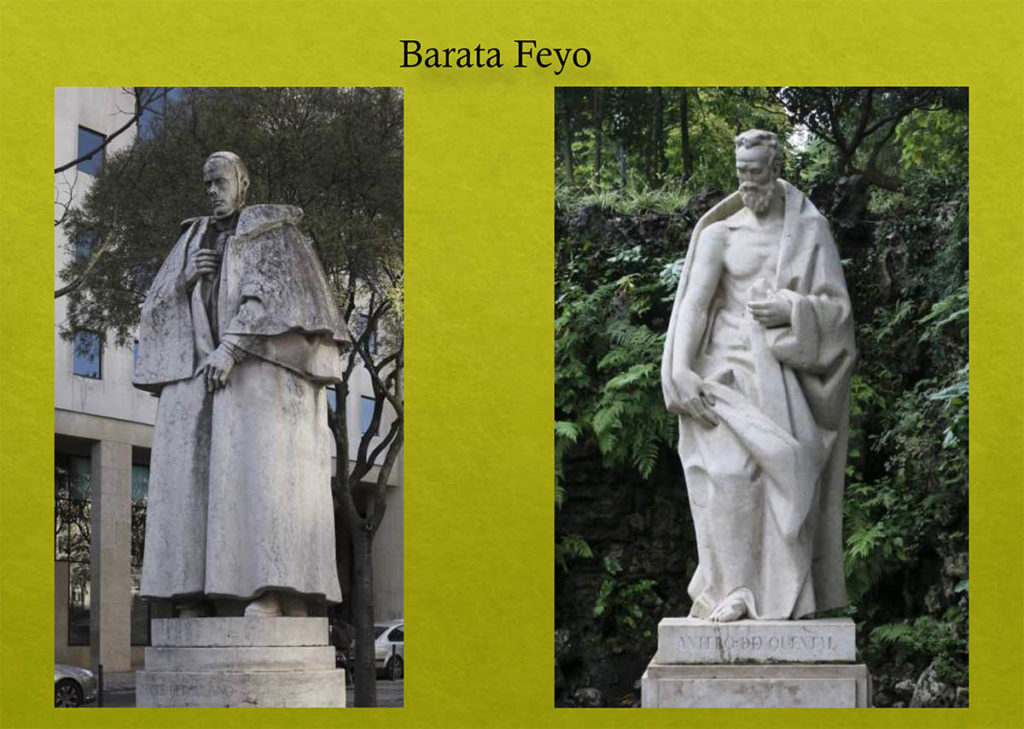

Many sculptors executed works for the Exhibition, such as Francisco Franco, Barata Feio and also Canto da Maia, António Duarte and others.

But the artists that António Ferro most praised and intended to be an example to be followed by Portuguese sculptors, as a recipe, were Leopoldo de Almeida and Barata Feio, who marked the limits of academicism.

Painters such as Almada Negreiros and his wife Sara Afonso, Bernardo Marques and Eduardo Viana, although they participated in the Belém Exhibition and exhibited in the SPN's salons, they maintained greater independence.

It is necessary to clarify that the "Exhibition of the Portuguese World" took place in 1940, when Hitler and Mussolini, allies among themselves and friends of Salazar, were at their peak, having militarily helped Franco's victory against the Spanish Republic and started, in 1939, World War II, in which, at the time, they had great victories.

The defeat of Nazi-fascism, particularly thanks to the military successes of the Soviet Army, culminating in the victory of the Allied forces in May 1945, determined the turning point in the world balance of forces and made Salazar, whose allies had been defeated, tremble.

The huge demonstrations with which, in Portugal, we celebrated this victory, gave an enormous boost to the Opposition forces and allowed the creation of the MUNAF and the MUD Juvenil, under the impulse of the Portuguese Communist Party.

In this wave of unity of the anti-fascist forces, progressive intellectuals played an important role. A role they had been playing for a long time, albeit discreetly. It is necessary not to forget that the genesis of the anti-fascist movement at the cultural level, inspired by the Marxist theory of historical materialism, came from the mid-thirties to being publicized by newspapers such as “O Diabo”, one of the directors of which was the lawyer Campos Lima (well known in Portimão), “O Sol Nascente” and the magazine “Vértice”.

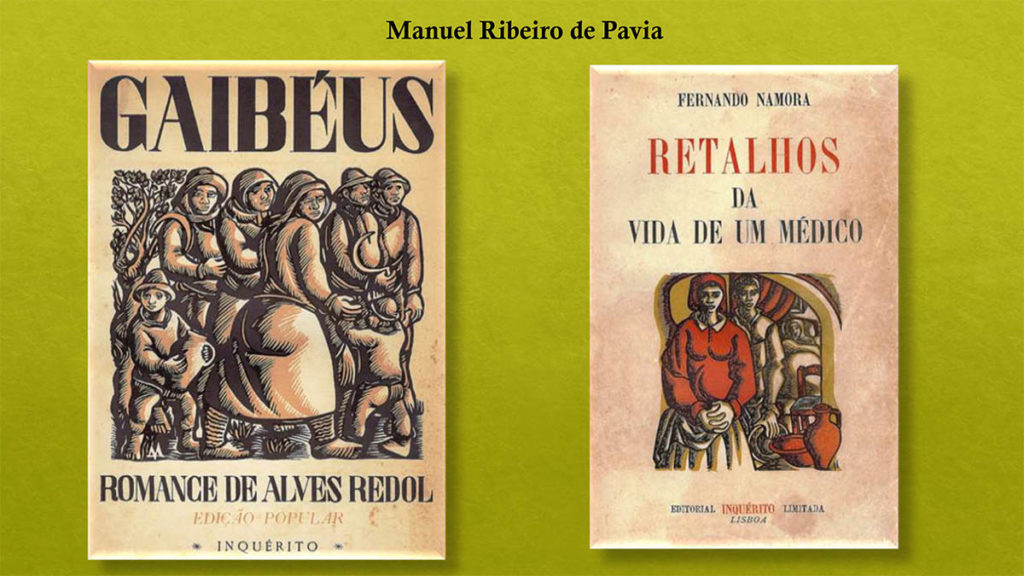

It was the important literary controversies developed by these periodicals that gave rise to the birth of neo-realism in literature, in defense of “useful art”, facing the real problems of society.

It was a new generation of writers that then emerged, demanding greater civic and cultural intervention from writers and artists, contrary to the ideals of the fascist regime.

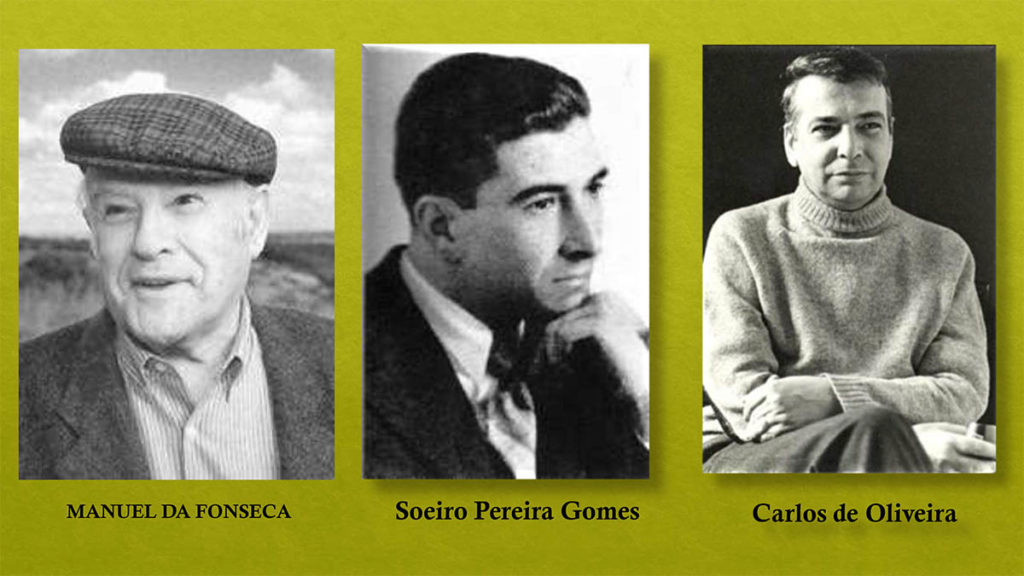

The highlights on this front were Alves Redol (Gaibéus-1939); Manuel da Fonseca (Rosa dos Ventos-1940); Soeiro Pereira Gomes (Esteiros-1941) and Carlos de Oliveira (A bee in the rain-1953).

These writers were joined by others, such as José Cardoso Pires, Ilse Losa, Urbano Tavares Rodrigues, Augusto Abelaira and Sttau Monteiro, who also focused on a broader concern, not only in terms of content, but also in terms of form.

In fact, it was the battle for content (without neglecting the form) that characterized this period, in which the Portuguese neo-realist movement emerged with force.

Right after the victory against Nazi-fascism, with the temporary retreat of Salazar and the growing forces of the Opposition, and following the already developed literary movement of neo-realism, progressive plastic artists gained strength to contest the political impositions of António Ferro, who closed the doors of the only large exhibition halls, which were those of the SPN (which after the war changed its name to the National Information Secretariat, SNI) and the Halls of the National Society of Fine Arts, where it was imposed a narrow academicism.

It was then a matter of conquering, through a broad unitary work, a direction open to modernity for the SNBA, which had large exhibition halls, hitherto closed to artists who were not adherents of the regime, and academics in terms of style.

It was thanks to a broad movement initiated by ESBAL students and other artists not adept at the regime, that a more open and democratic direction for the SNBA was managed, chaired by sculptor Anjos Teixeira.

It was from this victory, in 1946, that the General Exhibitions of Plastic Arts (EGAP) began, in the SNBA, which, for ten years, until 1956, constituted not only a true act of cultural confrontation with the fascist regime, but also a real incentive for free and uncommitted creativity, particularly of young artists, who until then had not had the chance to exhibit their works.

The ten years of the EGAP's existence have not passed without attacks of repression. One of the exhibitions was closed by PIDE after the opening and several paintings removed.

But the artists resisted and the EGAP constituted an opening and a suitable field for the presentation of artistic manifestations that struggled for the conquest of free expression, for which each artist was interested in expressing as background and form and, ultimately, contributing to foster a renewal of the Portuguese artistic panorama.

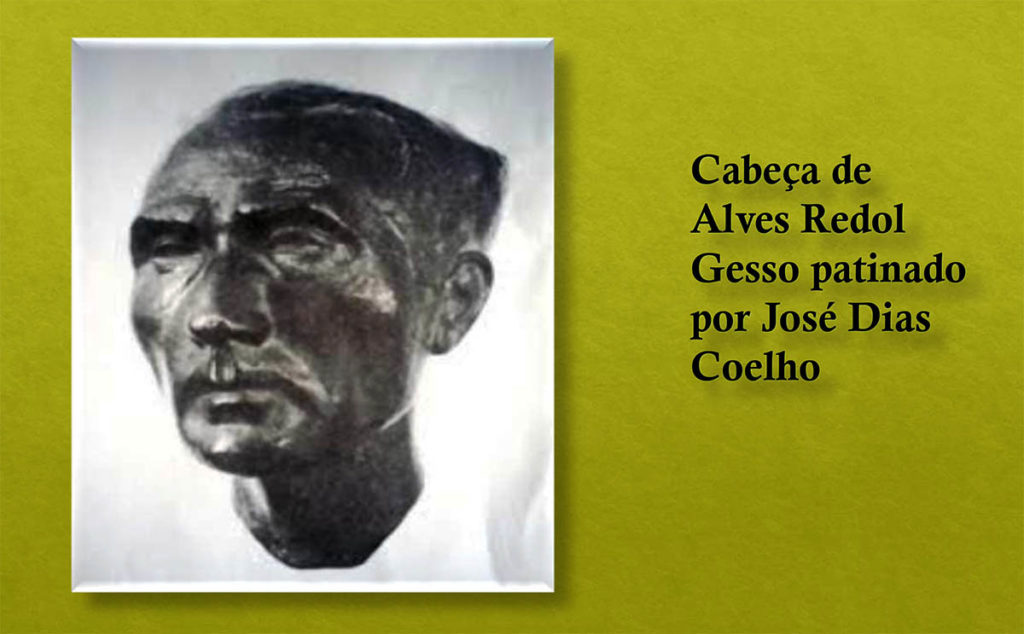

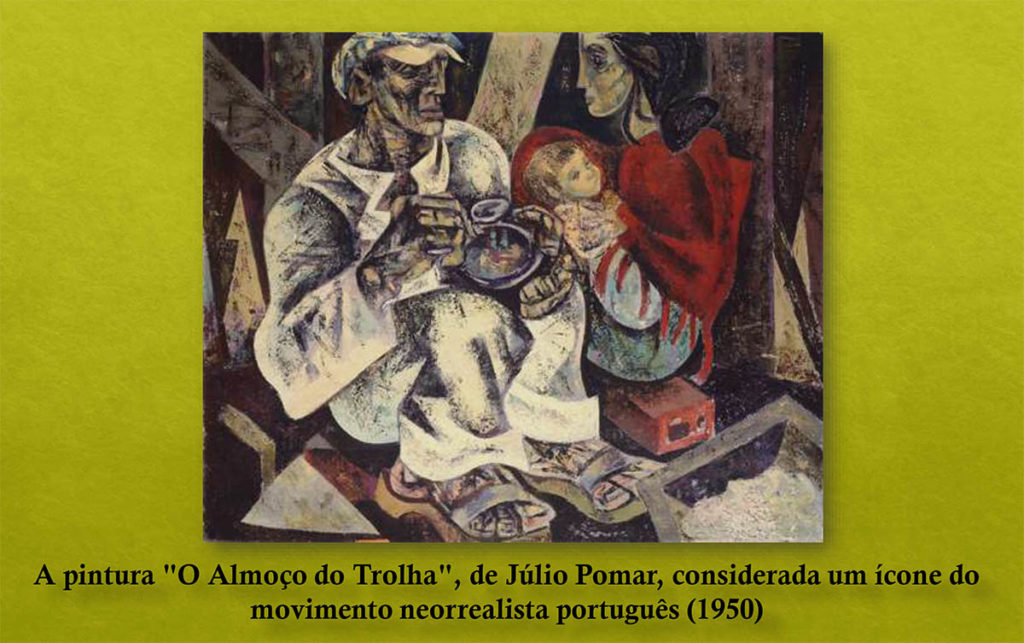

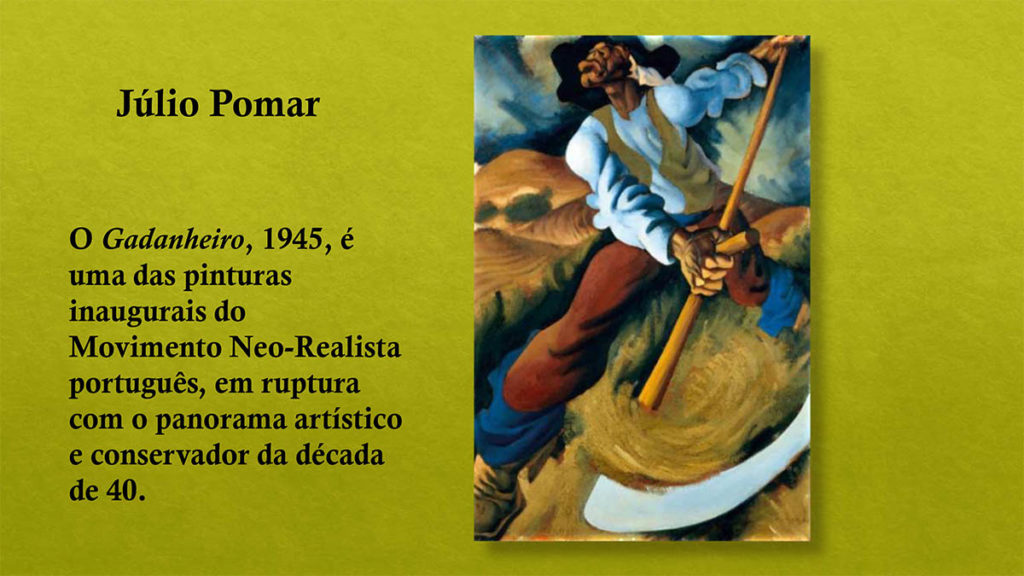

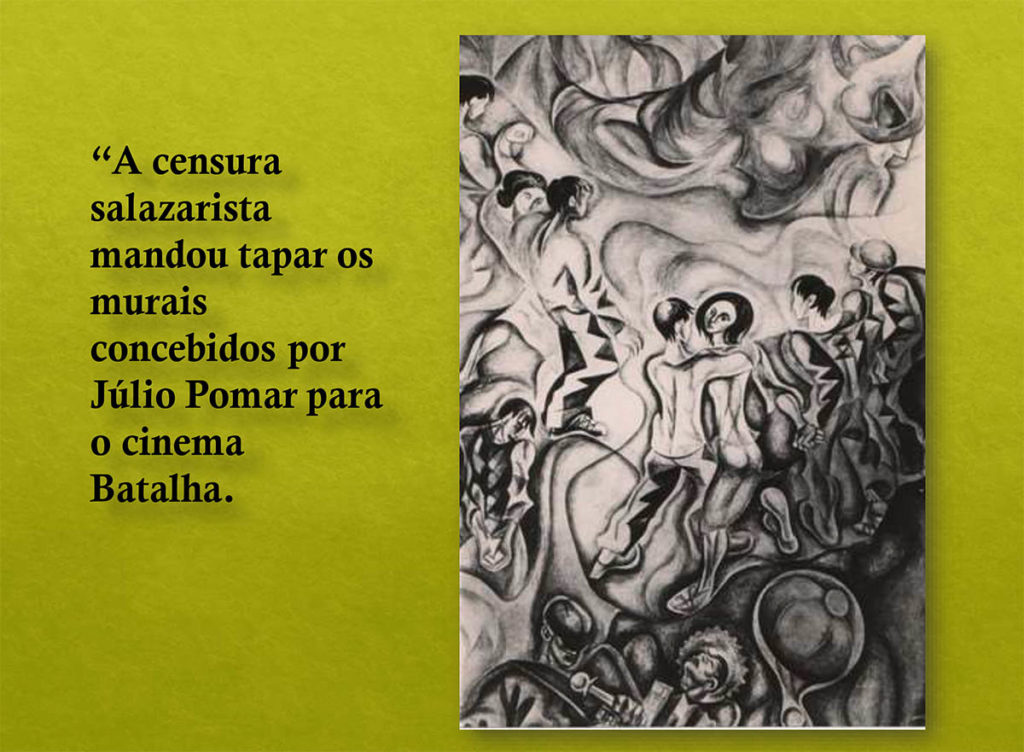

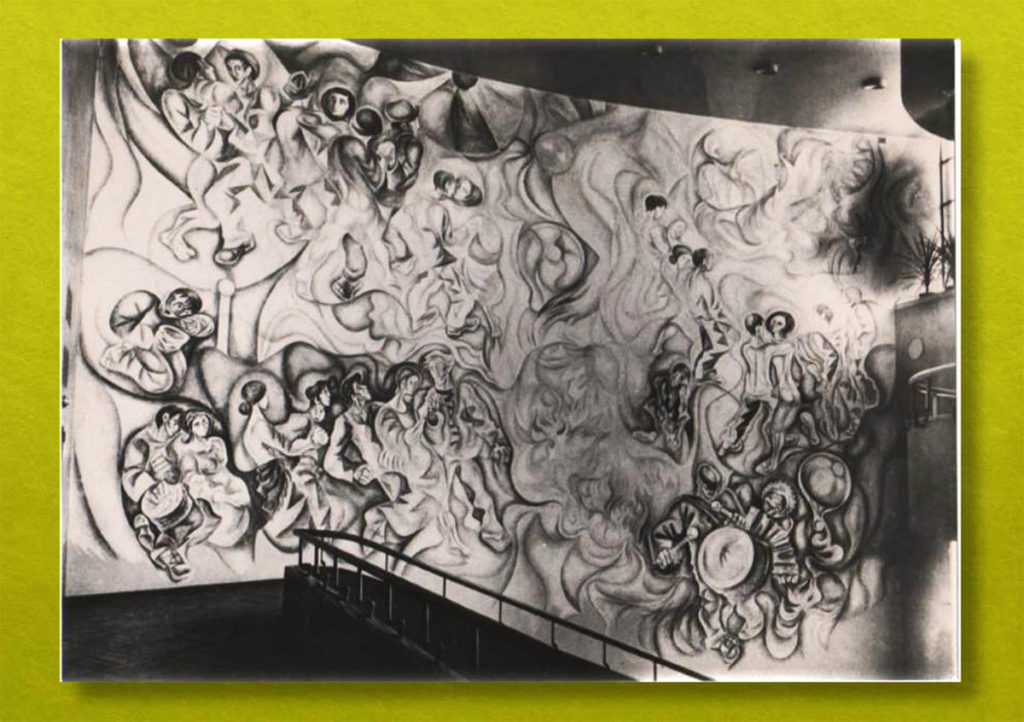

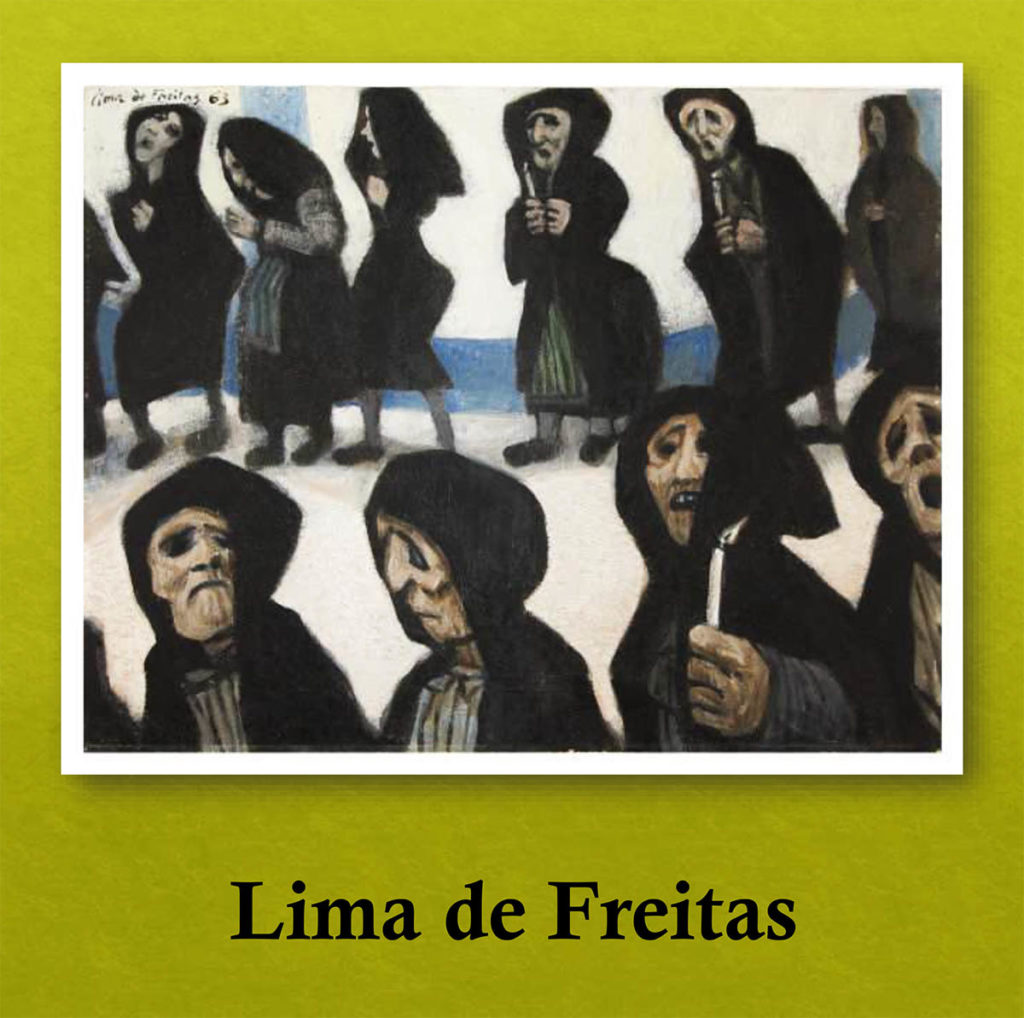

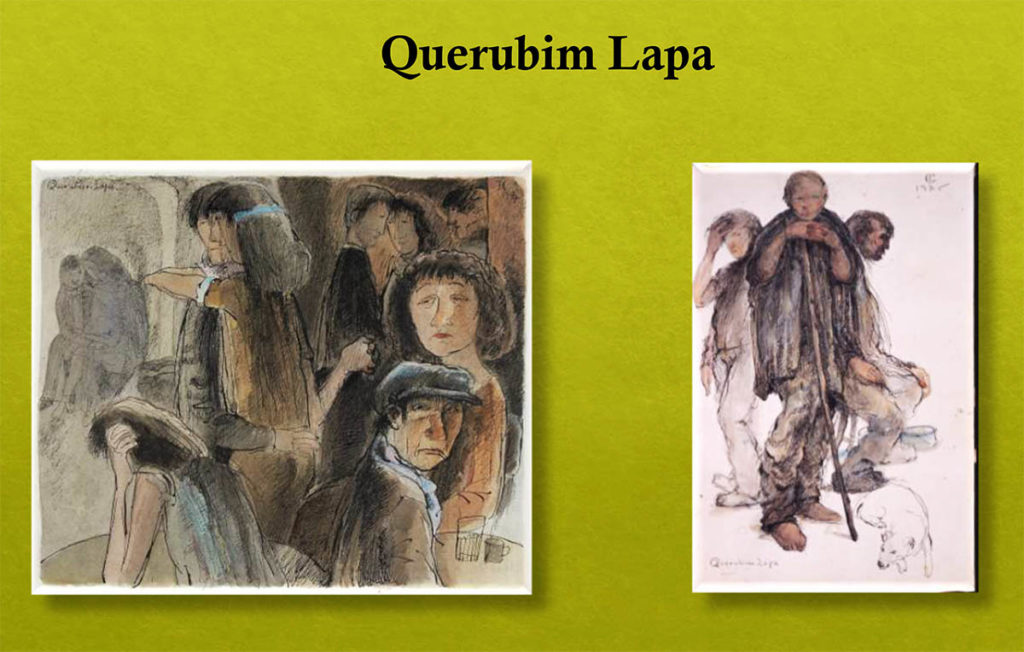

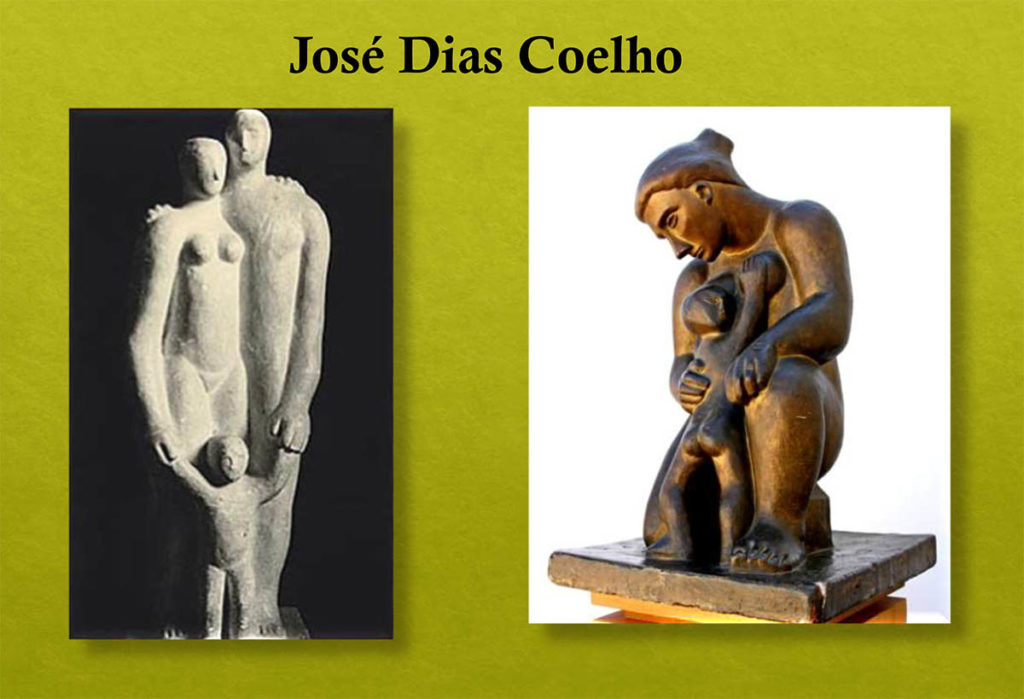

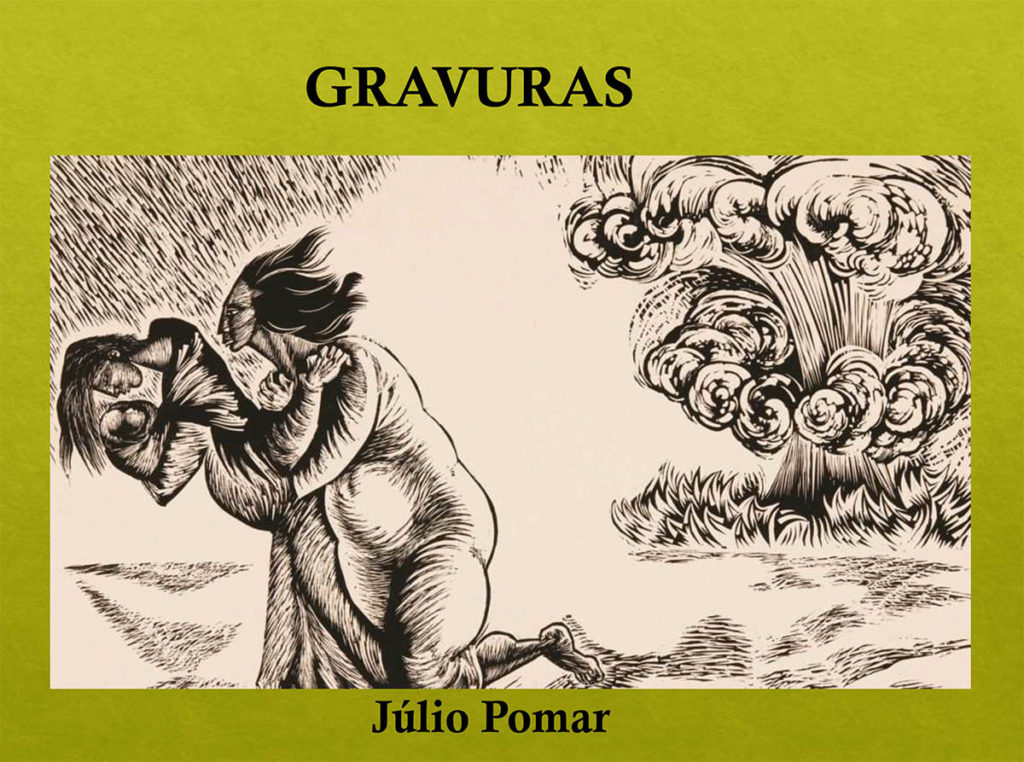

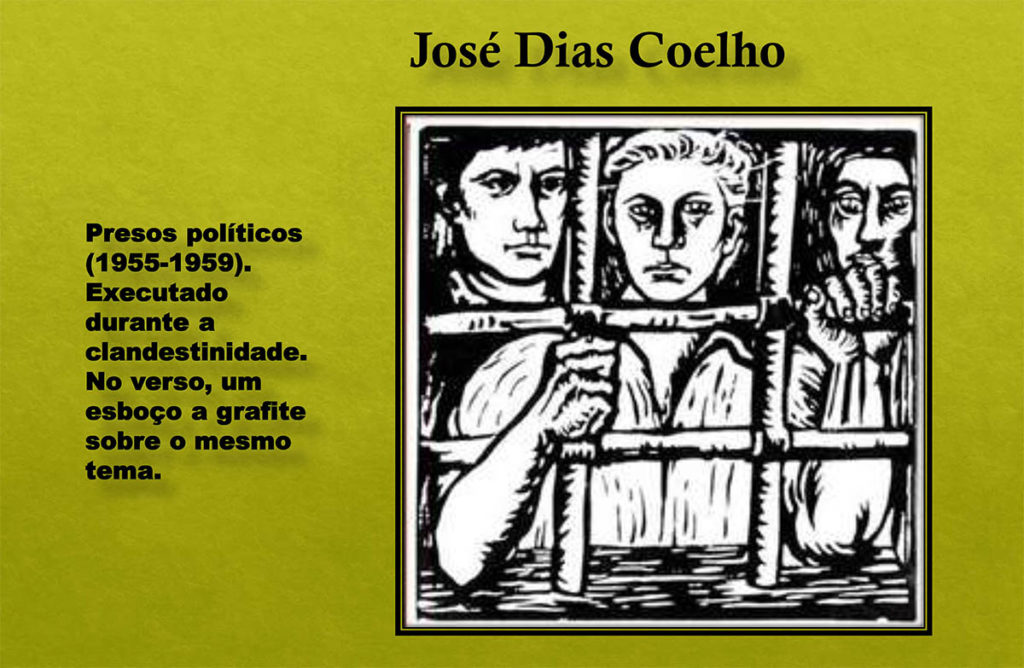

Thus, at the EGAP, with the strength and vigor of youth, new layers of artists emerged, who were not welcomed in António Ferro's SNI Salons. These young rebel artists would assert themselves in the future as outstanding artists in Portuguese Art. Among them Júlio Pomar, whose mural in the cinema Batalha do Porto was ordered to be covered by PIDE, for representing popular scenes from the S. João festival in Porto (photos remain), Lima de Freitas, Querubim Lapa (born in Portimão), the sculptors Maria Barreira, Vasco da Conceição, and also José Dias Coelho, and Jorge Vieira, with their project for a monument to the unknown political prisoner (already executed in Beja).

Many other renowned artists started in these exhibitions, such as the painters Rolando Sá Nogueira, João Hogan, Rogério Ribeiro, Maria Keil, and the architects Sena da Silva, Castro Rodrigues, Hernani Gandra and P.Cid.

It was clear that, if neo-realism gained greater visibility from the EGAP, and prevailed in them, the truth is that they presented a plurality of aesthetic options resulting from the scope and political unity objectives of their organizers. Surrealists and abstract artists participated in them for as long as they wanted.

The very evolution of those who, having been cultists of the practice and plastic reflection of neorealism, moved to other aesthetic options, proves that there they had gained the powerful impulse of nonconformism and the struggle for the new, which catapulted them to new experiences, such as Júlio Pomar, Lima de Freitas, Querubim Lapa and Rogério Ribeiro.

A little-known aspect is that the General Exhibitions of Plastic Arts welcomed in their salons, for the first time, photography as an artistic expression, since, until then, it was only exhibited in photo clubs and photography exhibitions for amateurs. Participating in them, with photographs, Victor Palla (later published in the book “Lisbon, Sad and Happy City”), architect Keil do Amaral and Augusto Cabrita, the great photographer with a neo-realist theme.

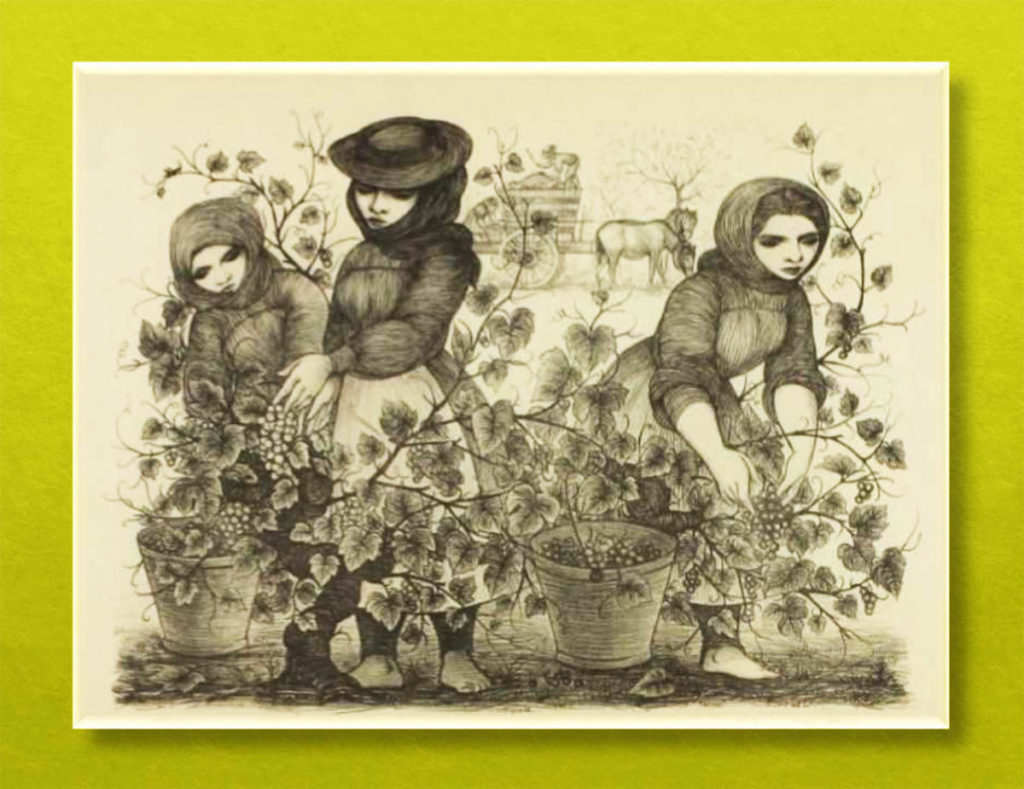

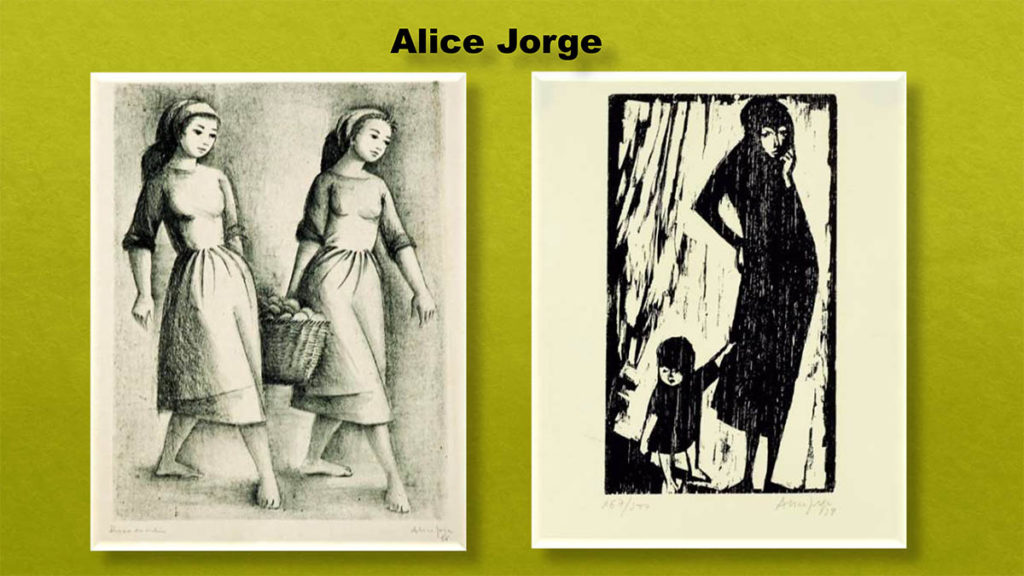

Also for the first time, the EGAP presented printmaking, in its various modalities, according to the criterion that printmaking is one of the forms of art that facilitates wide dissemination among the popular classes.

Engraving was not taught at the Escola Superior de Belas Artes, and it was from the increase given by the EGAP that the artists who exhibited there created the Engraving Cooperative, in 1956, which gave an enormous increase to this form of art.

With the creation of the Gulbenkian Foundation, in 1956, there is no doubt that greater facilities opened up to Portuguese artists.

But the truth is that the front of the antifascist intellectuals never allowed room for maneuver and credibility to the attempts to capture the fascist regime.

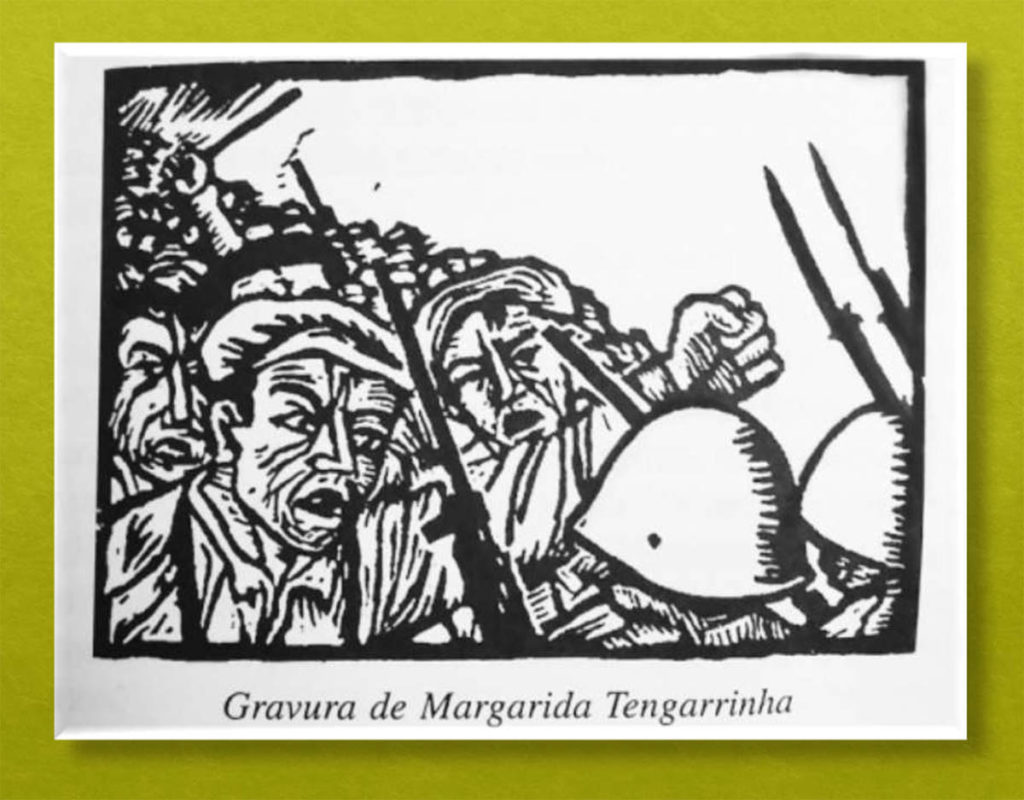

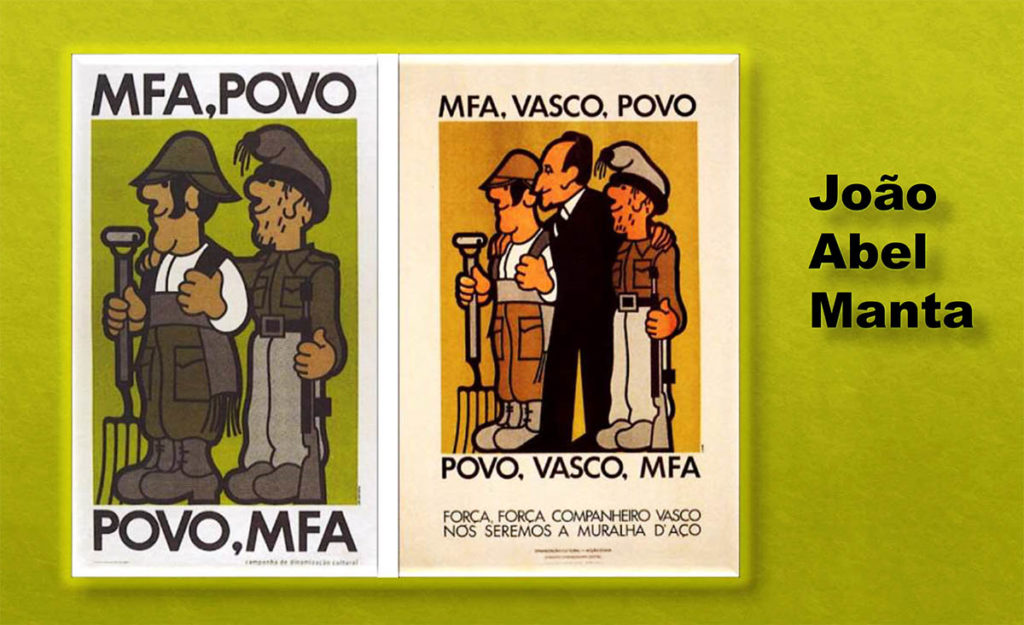

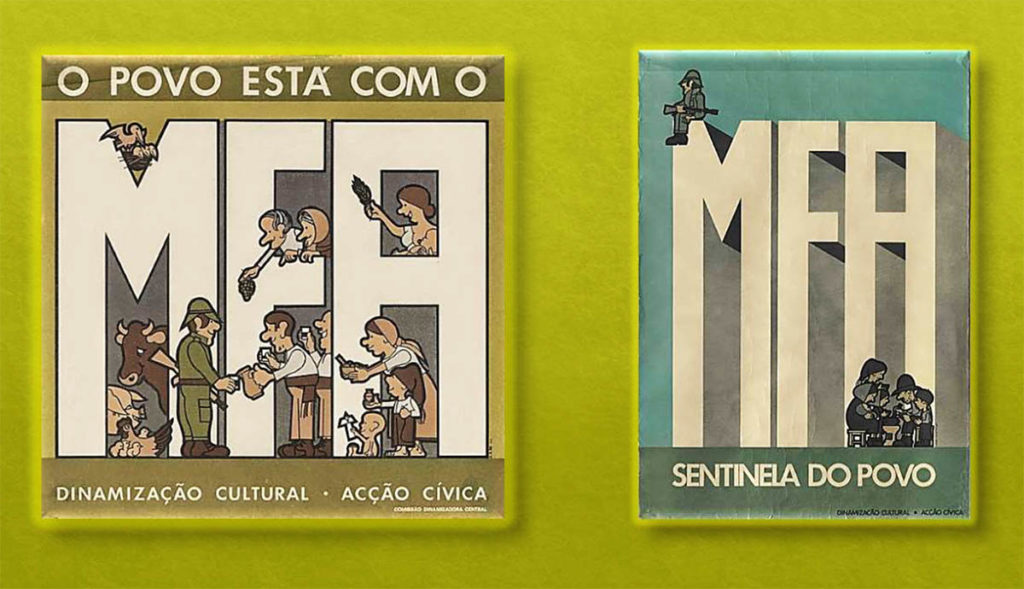

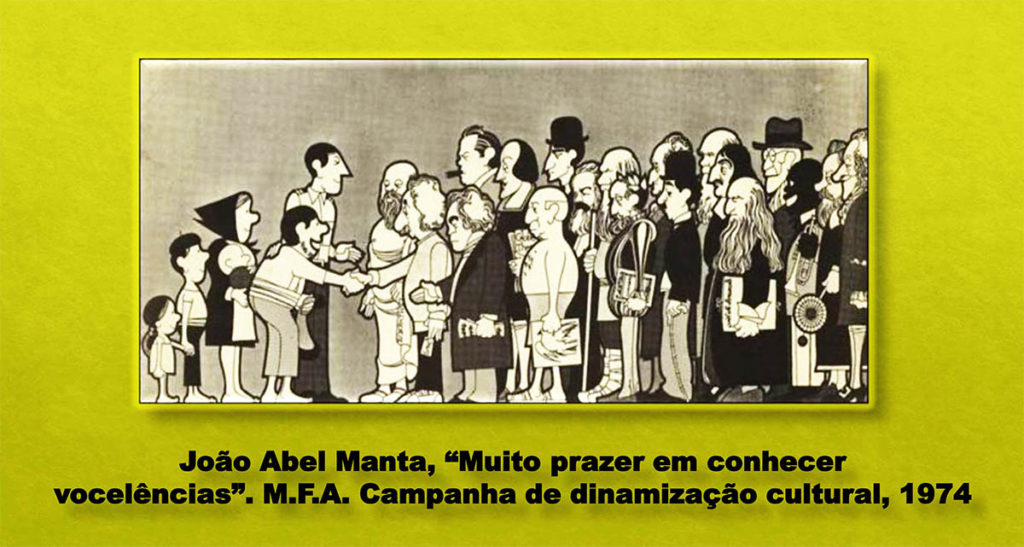

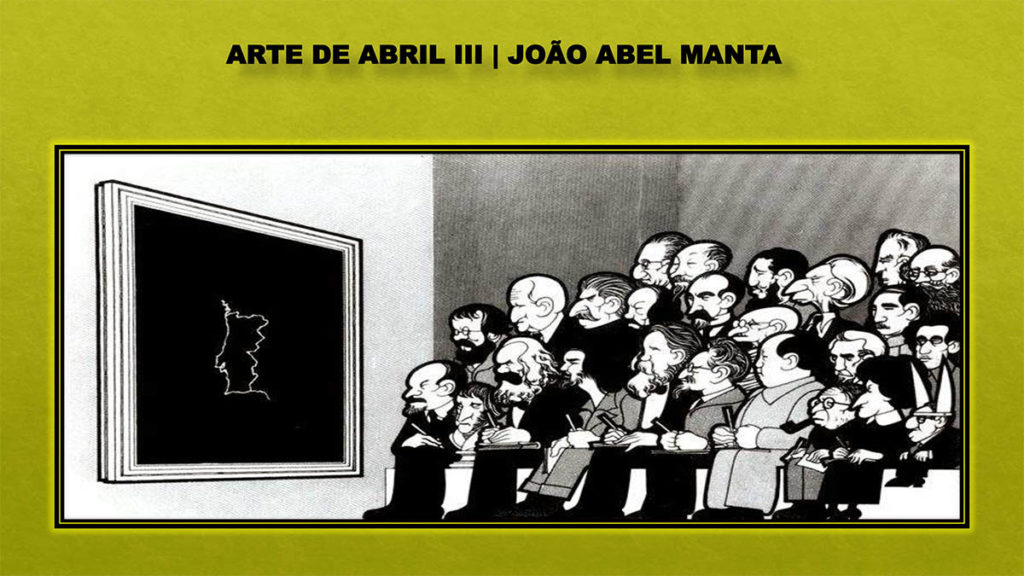

And in the revolution of the 25th of April, they participated with their art in the exalting moments of the MFA's victory. As did Cipriano Dourado, with his engravings, and the great artist João Abel Manta, with his posters.

Note: This is the lecture given by Margarida Tengarrinha, member of the Portuguese Communist Party, Resistant Anti-Fascist, former deputy to the Assembly of the Republic after the 25th of April and Plastic Artist, on Monday, the 22nd of April, in the talk about “The Art before and after the 25th of April of 74”, which took place at the Café-Concerto of the Municipal Theater of Portimão.

The author writes according to the previous Spelling Agreement.

Comments