Eyebrows that are very mobile and capable of expressing subtle emotions may have been essential in non-verbal communication in recent human evolution and, with that, in human beings' capacity for empathy and the evolution of societies.

This hypothesis is suggested in a study carried out at the University of York by a team in which Ricardo Miguel Godinho, a researcher at the Interdisciplinary Center for Archeology and Evolution of Human Behavior (ICArHEB) at the University of Algarve (UAlg), was integrated. This research was partially funded by the Foundation for Science and Technology.

The main conclusions of this work by the group of researchers, entitled “Supraorbital morphology and social dynamics in human evolution”, were published on April 9 in the journal “Nature Ecology & Evolution”.

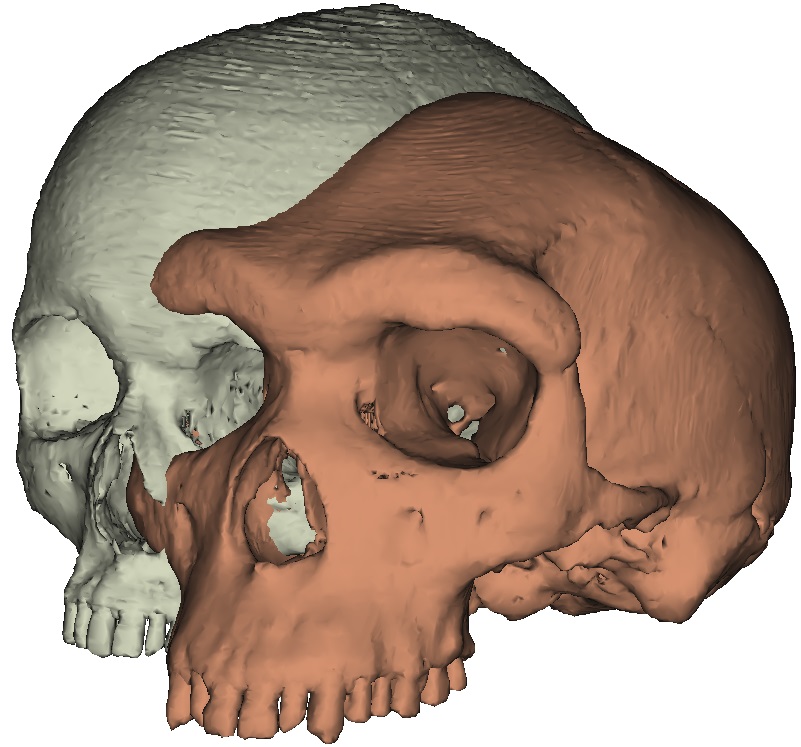

Ricardo Miguel Godinho was part of a group of researchers as part of his PhD at the University of York, where he carried out several simulations, «using an iconic fossil hominid skull, Kabwe 1, which is deposited in the collection of the Museum of Natural History in London», according to to UAlg.

This specimen, like the other ancestral human species, has very prominent supraciliary arches which, "like the armatures of deer, could function as a permanent sign of dominance and aggressiveness."

«In our species, Homo sapiens, the supraciliary arches have become smaller due to the evolution of the forehead towards a more vertical and smooth shape, making the eyebrows more visible and capable of a more diversified and subtle range of motion», explains Ricardo Godinho.

This change "allowed the development and refinement of non-verbal communication through the eyebrows, which is essential in the transmission of subtle emotions such as sympathy and recognition", determined the investigation. In the opinion of the researchers, "this ability will have allowed for greater understanding and cooperation between people, essential for the formation of large-scale social networks."

Paul O'Higgins, professor at the University of York and co-author of the article, pointed out, for his part, that “our forehead's refined non-verbal communication function will initially have been a side effect of the reduction in the size of our faces over the last 100.000 years old. This process of facial reduction has accelerated over the last 10.000 to 20.000 years, when we switched from hunter-gatherers to farmers – a lifestyle that resulted in less physical activity and a less varied and softer diet.”

Another co-author of the study, Penny Spikins, also a professor at the University of York, added that "eyebrow movements allow us to express complex emotions as well as perceive the emotions of others." This makes eyebrows "essential to explain how humans became so good at interacting with each other."

«Raising your eyebrows quickly (flash eyebrow) is an intercultural sign of recognition and availability for social interaction. Lifting them in the middle of the forehead expresses sympathy. Light, small eyebrow movements are essential to identify trust and deception. On the other hand, it has been shown that people who have limited eyebrow movement due, for example, to the application of Botox, are less able to cause empathy and to identify with the emotions of others», explained the researcher.

To arrive at this hypothesis, the scientists of the team in which Ricardo Godinho is inserted, studied the skull of the A man from Heidelberg Kabwe 1, ending up concluding “that the two most common hypotheses to explain the presence of prominent supraciliary arches, the spatial and masticatory hypothesis, are not sufficient to explain the massive arch of Kabwe 1”, according to UAlg.

The spatial hypothesis "proposes that the supraciliary arches are formed to occupy the space between the cranial cavity and the orbits". The masticatory hypothesis "proposes that the supraciliary arches develop to stabilize the skull against the forces developed during mastication".

“Through 3D modeling software we modified the massive supraciliary arch of Kabwe 1. As it was possible to reduce it significantly, we realized that the arch is not that big just because of the space between the skull and the orbits”, explained the researcher from UAlg.

«Then we simulated chewing on several teeth and we realized that the supraciliary arch does not significantly deform during chewing, the results being practically the same between the original skull and other versions with the reduced arch. This means that the arch has limited relevance for stabilizing the skull during mastication,” he added.

This study thus contributes «to the long debate about why other hominins, including our ancestral species (A man from Heidelberg), had supraciliary arches so protruding and we, Homo sapiens, we have a vertical forehead with very reduced arches», concluded the University of Algarve.

Comments