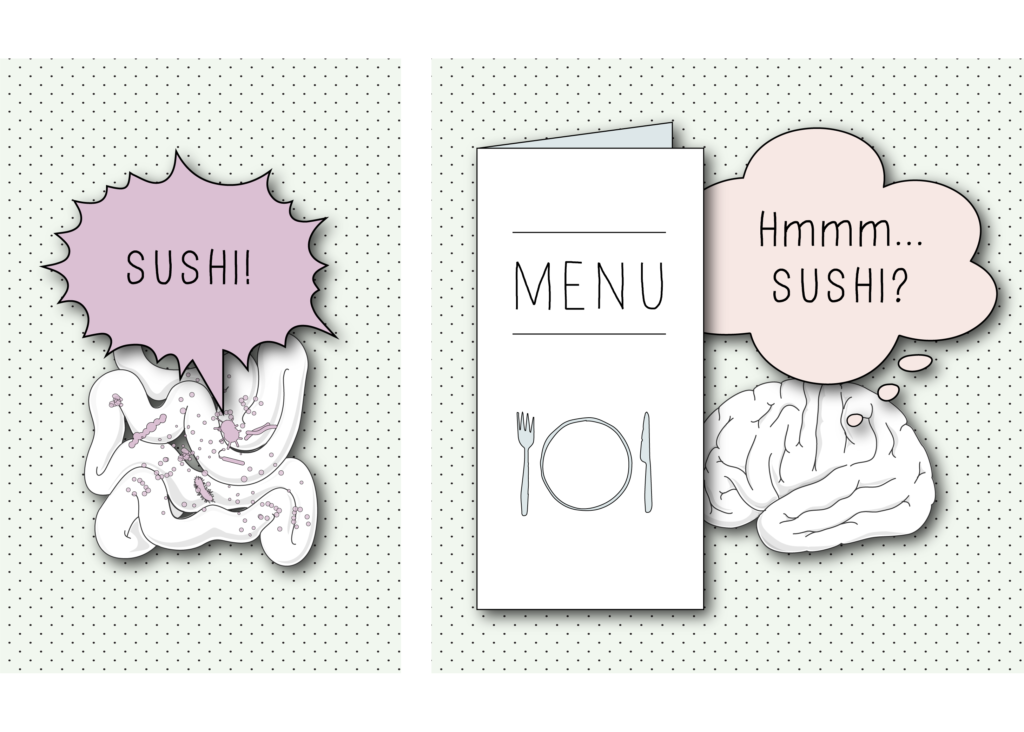

Do the bacteria that inhabit our intestines influence our food choices? A study shows, for the first time, that this idea is not entirely unreasonable.

Do the bacteria that inhabit our intestines influence our food choices? A study shows, for the first time, that this idea is not entirely unreasonable.

A team of neuroscientists has found that bacteria that live in the gut are able to control the food choices of animals by “talking” to the brain. In particular, they identified two species of bacteria that radically influence these choices.

The impact of the “microbiome” – the bacterial community that lives in the intestines of animals, including humans – on health is undoubted. For example, diseases such as obesity have been linked to the composition of the diet and the type of bacteria that inhabit the intestine.

However, from there to thinking that simple microbes can control our way of acting and that we are not totally in charge of our decisions, it is a big step. Or maybe not, according to the study now published in the journal PLOS Biology by a team from the Champalimaud Center in Lisbon, in collaboration with a colleague from the University of Monash, Australia.

The new study was carried out on the fruit fly, which allowed scientists to dissect the complex interaction between diet, brain and gut bacteria.

The team demonstrated that the impact of the microbiome is so profound that even when flies were fed a diet devoid of certain essential nutrients, intestinal bacteria prevented them from developing an appetite for those nutrients.

More: they also protected the flies from the consequences of this type of food shortage. In fact, the bacteria literally reprogrammed the body's nutritional needs, to the point of safeguarding the fertility of the flies, which would otherwise have been abolished due to the poor quality of the diet.

Because naturally occurring foods are so complex, scientists created a synthetic food that allowed them to manipulate the fruit flies' diet by removing essential amino acids. These are the basic components of proteins that, not being manufactured by the body, must be supplied by the food that is eaten.

And in fact, the team observed that it was enough to remove a single essential amino acid, whatever it was, to increase the intake of high-protein food. When faced with dietary deficiencies, “the animals are thus able to adjust their food choices,” says Zita Santos, co-author of the new study, which was led by Carlos Ribeiro, principal investigator at the Champalimaud Center.

To test the microbiome's effect on food choices, scientists subjected fruit flies to essential amino acid deprivation in the presence and absence of five species of bacteria naturally present in their gut.

They then found that, surprisingly, flies with the correct microbiome did not develop an appetite for protein-rich food – and even continued to reproduce despite the dietary deficiency they were being exposed to.

The results exceeded expectations: the presence of only two particular species of intestinal bacteria was enough to cancel out the protein intake by the animals deprived of essential amino acids. “With the right microbiome, fruit flies are able to face unfavorable nutritional situations”, says Zita Santos.

“Fruit flies have five main species of bacteria in their intestines, while humans have hundreds,” stresses Patrícia Francisco, another co-author of the study. This highlights, in the authors' view, the importance of carrying out these studies in simpler animal models, such as this insect, to begin to unravel an issue that may be crucial for human health.

But how do bacteria manage to act on the brain to alter the appetite for certain foods? “Our first hypothesis was that the bacteria would be supplying the flies with the essential amino acids they needed”, replies Zita Santos. "But the reality seems to be more complicated."

Intestinal bacteria “seem to be inducing a metabolic alteration that acts directly on the brain and body, simulating a state of protein satiety”, adds Zita Santos.

In summary, this study not only shows, for the first time, that the microbiome acts on the brain to change the food preferences of animals, but also that, to produce this effect, intestinal bacteria resort to a new mechanism, as yet unknown.

Read the full article here:

http://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.2000862

Author Champalimaud Foundation

Science in the Regional Press – Ciência Viva

Comments