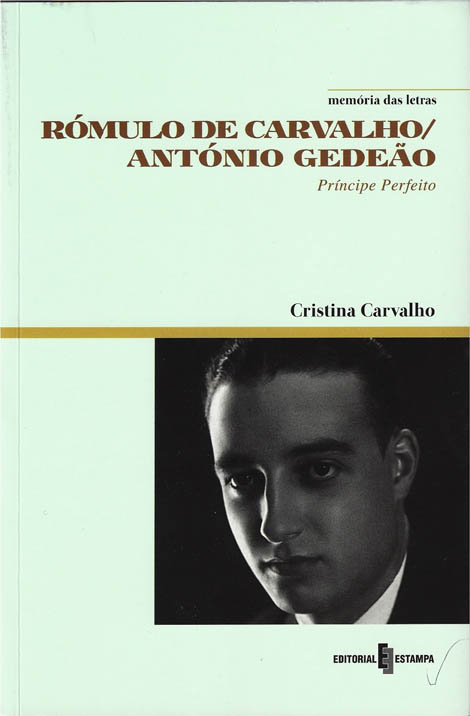

António Piedade, coordinator of the Science in the Regional Press/Ciência Viva project, interviewed Cristina Carvalho, daughter of the poet, teacher and educator, about her biography «Rómulo de Carvalho/António Gedeão», which has just been published by Editorial Estampa :

António Piedade, coordinator of the Science in the Regional Press/Ciência Viva project, interviewed Cristina Carvalho, daughter of the poet, teacher and educator, about her biography «Rómulo de Carvalho/António Gedeão», which has just been published by Editorial Estampa :

António Piedade (AP) – Why did you write the book, why did you write it now?

Cristina Carvalho (CC) – Never in my life had it occurred to me to write these biographical notes about my father's life. Yes, I agree that this thought could have even warmed me, that it would be natural for me to be able to write about him, and it would be! But such an idea never happened to me. It was because of an invitation from the publishing house Estampa, once, twice, three times, insisting, that this happened.

It was not easy. As I say at the beginning of the book, it wasn't easy. For psychological reasons, for sentimental reasons, for several reasons not worthy of interest to anyone reading this interview, but very important to me. However, I ended up accepting the invitation. And I never regretted it. It was a unique experience, writing these brief biographical notes.

AP – What kind of readers did you have in mind when you structured and wrote it?

CC – I never had a certain type of reader in mind, although I knew and could foresee the existence of a readership much more interested than others in this type of narrative and about the person who was Rómulo de Carvalho/António Gedeão, starting with that huge number of students who are alive, who have known and appreciated and even loved him.

So, as I said, I didn't structure the book or write it with anyone in mind, especially. Although it is a narrative with certain very specific characteristics, this was another book I wrote after I managed to free myself from certain attitudes and certain views.

AP – What kind of readers do you expect to read the book?

CC – This answer follows on from the previous one. Indeed, there are “types” of readers if we want to catalog it that way. And there are also “types” of books.

If you ask me what kind of readers I hope will read this book, I would say, all kinds of readers, although I know that's not possible. A writer writes to be read, he does not write with the determined aim of being read by this or that. But it is known that this is not the case.

There is, in fact, on everyone's part an inclination or an appetite or a taste or pleasure or whatever we want to call certain books. I don't like certain literature as well as the person who goes there on the bus may like what I don't like. It's a cultural attitude, isn't it? If a person has learned to know and like and choose a certain writer or a certain type of writing or certain topics, it will be difficult for him to stick with another type of writing, just out of curiosity. And sometimes this curiosity can lead to unthinkable situations, this is also true.

I can judge that I don't like that book and, after all, I like it a lot! What I would really like is that this book could be useful and be read by many, many people.

AP – Rómulo de Carvalho wrote the main study on the History of Education in Portugal, from the beginning of nationality until the 25th of April. In the proximity you maintained with your father, can you tell us something about his opinion regarding the state of education in Portugal after 1974 and until the last years of his life?

CC – Effectively, the “History of Teaching in Portugal”, edited by the Gulbenkian Foundation and which has already seen several reprints, is considered by many people interested in pedagogy and teaching in Portugal as a masterpiece on this subject.

I've heard it called a kind of “bible” for teachers and technicians in this field. It is, in fact, a reference work that offers a very interesting and sometimes surprising overview of the evolution and the various cycles of education in our country, from the founding of the nationality until the 25th of April 1974. Significantly, his approach to the history of teaching ended on that date.

Teaching, as I understand from reading the “Memoirs” and from the private and public approaches he made, was seen as a fundamental issue for the development of society.

In the period following the Revolution, as in other areas of Portuguese life, teaching and schools underwent great upheavals and disturbances. It was in this situation that he abandoned, retiring early, the career to which he had dedicated his whole life. There can be no greater expression than this of what he would think about the direction that teaching was taking.

However, I recommend reading his “Memoirs” where he expresses on several occasions what he thought about this subject.

AP – Rómulo de Carvalho is our “patron” of science dissemination. How does Cristina Carvalho classify the evolution of science dissemination in Portugal in recent decades?

CC – I will not be the most qualified person to answer this question, but, from what we can observe with naked eyes, there seems to be no doubt that giant steps have been taken in both the development of scientific research in Portugal and its insertion in the international science networks, as well as in scientific dissemination.

Fortunately there are high-ranking people who shine in the firmament of international Science and among these people there are many young people who have distinguished themselves. I only hope that this journey continues and that it can give the country and the world great contributions to global development and in all senses.

Antonio Piedade

Science in the Regional Press – Ciência Viva

Comments