On my previous article, I recalled that most of the measures of the Pombaline project of “Restoration of the Kingdom of the Algarve” date from the year 1773 and therefore mark its 250th anniversary.

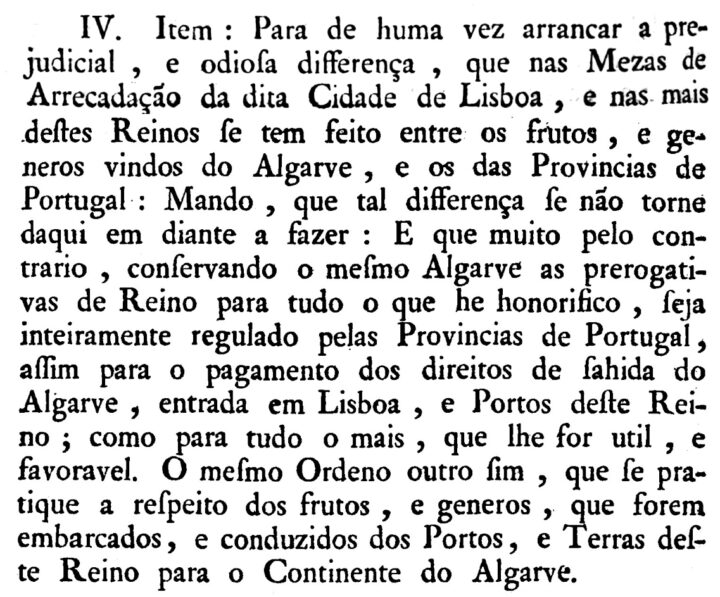

Among these, one of the most relevant was the letter of law of February 4th, which ended the “odious difference” between the Kingdom of Portugal and the Kingdom of the Algarve in terms of customs discrimination that existed in the Algarve region. Now, despite being able to advance the idea that the odious difference was much more than merely “customs”, what does this piece of legislation translate into after all?

In reality, the Kingdom of the Algarve was treated as if it were a foreign region, and the fruits and products from there, which left through its customs ports, or the products from the Kingdom of Portugal that entered there, even paid the double the taxes applied in other Portuguese ports, such as Lisbon, Setúbal, Figueira da Foz, Porto and Viana do Castelo.

In this way, the Pombaline law sought to ensure that from now on the collection of rights would be regulated by the other Portuguese provinces, with a view to the economic integration of the Kingdom of the Algarve into the rest of the Kingdom of Portugal. However, the doubling of taxes was not the only problem that the Marquês de Pombal faced in the Algarve.

Being completely excluded from the colonial trade routes, we did not find, in the Algarve, any port of great importance. Even so, some moderate dynamism was seen in the scope of maritime trade, mainly in the port of Faro, for two essential reasons: the fruits that the region produced and its scale position between the Atlantic and the Mediterranean.

As far as fruits are concerned, the production of figs and grapes, exported as raisins, almonds, sweet oranges, lemons, cork, was of some interest to the markets of Northern Europe, where such fruits were not produced and were even seen as exotic. The charge of the port of loading Faro reports the departure of said fruits towards, for example, London, Liverpool, Dublin, Ostende, Ghent, Rotterdam, Amsterdam, Hamburg, Stockholm and even towards New York, Philadelphia and Boston, among other destinations.

With regard to the scale between the Atlantic and the Mediterranean, there was actually also some trade with the south of Spain, the south of France and North Africa. However, the Algarve was particularly interested in trade with Praça de Gibraltar: to supply this enclave, conquered by the British from the Spaniards in 1704 and definitively in their possession from 1713 with the signing of the Treaty of Utrecht, trade with the Algarve, given that relations with Spain were not always peaceful.

The other problem that Pombal faced in the Algarve is related to its wider, national policies, in an attempt to reduce external economic dependence, which means, in fact, economic dependence on the British. This economic dependence on the British was also evident in the Algarve – any reflection on the similarity of this reality with the present is freely up to the reader! –, to the extent that English trading houses were predominant in the transactions that took place in the region.

Indeed, trade was centralized in Faro, where products and fruits from all over the region were sent through emissaries throughout the territory. The main commercial houses responsible for the transactions belonged to foreigners, mainly English, descendants of families settled there for decades: this was the case of the English João Lamprier, Parcar Pitts, João Keating, or the Swede Bar Avent who formed a company with the Englishman João Crespim.

These men effectively dominated the trade routes with the North Atlantic, as well as with the Mediterranean, and had investment capacity, characteristics that it was difficult for national traders from the Algarve to cope with. Not even the Pombaline legislation integrating the Kingdom of the Algarve into the Kingdom of Portugal could, as was its intention, change the primacy of the English in the commercial domain, opening up space for national investors.

The decline in English influence would only be felt towards the end of the XNUMXs, combined with interests related to transatlantic colonial trade from which the Kingdom of the Algarve was excluded. And by keeping itself that way, excluded, it never managed to get out of its insignificance as a commercial warehouse.

Author: Andreia Fidalgo is a historian and writes according to the rules of the previous Spelling Agreement

Note: This article is the second in a small series that will mark the 250 years of the main measures of the Pombaline project of “Restoration of the Kingdom of the Algarve”. The next article will address the topic of agriculture.

Comments