In your last article on “The Covid-19 and the two Achilles heels of the Algarve”, here in Lugar ao Sul, Gonçalo Duarte Gomes consciously and thoughtfully recalled the vulnerabilities of the Algarve region to the current pandemic, but ended with a message of hope, writing that “The night is always darker before the dawn. But, infallibly, the sun rises again”.

Today, I return here to Lugar do Sul to reinforce this message of hope, remembering that the History of Humanity has already been subject to similar adversities and that, invariably, History reminds us that periods of crisis are cyclical and that Humanity always comes back to find her balance in the constant struggle to survive and stay sane in difficult times.

In recent weeks, the Black Death has often been recalled in association with the rapid spread of the new coronavirus. The Black Death remains in our imagination as one of the deadliest epidemics in history, absolutely overwhelming, responsible for decimating a significant part of the population.

In fact, this epidemic had very disastrous repercussions in the Asian continents – where it originated – and in Europe, especially between the years 1346 and 1353, and it is estimated that it was responsible for the death of about 25 million people in Europe alone, the which accounts for about a third of the population.

The disease was caused by the bacteria yersina pestis and, it seems, transmitted to humans through the bites of fleas and lice, at a time when hygiene and sanitary conditions were evidently very precarious or even non-existent.

In Portugal, the Black Death started in 1348, probably around S. Miguel, that is, at the end of September. During the next three months, it is estimated that this epidemic was responsible for the death of about one third to half of the Portuguese population, causing the country to plunge, like other European territories, into a serious demographic and economic crisis.

The outbreaks of the Black Death did not last until the XNUMXth century and continued to devastate periodically, with greater or lesser intensity, the country, as well as other parts of the globe, until the XNUMXth century, although without the Dantesque repercussions of the previous medieval period.

Because we associate this epidemic to the Medieval Period, it always seems to us a reality that is too far away and even unimaginable nowadays. In fact, although we are now dealing with a very worrying pandemic situation, the medieval Black Death occurred in a scenario that would be currently unthinkable, as we are today at an absolutely remarkable level of scientific evolution and development, without any possible comparison with the period in which the yersina pestis caused its greatest victims.

These days, given the spread of Covid-19, we are not lacking in recommendations on the various ways to prevent contagion and detailed information about the disease and the most common symptoms; There is also no lack of health professionals committed to treating, in the field, the patients who are increasing day by day, as well as teams of scientists who make every effort to investigate and learn about the new coronavirus, seeking diligently to create a vaccine and effective drugs to combat it.

And, moreover, of course, this pandemic we are now dealing with is not expected to lead to the disappearance of a third of the world's population, which would undoubtedly be even more catastrophic than the already rather alarming scenario in which we now find ourselves. .

Contemporary scientific development has brought absolutely remarkable progress to medicine, with an exponential increase in the average life expectancy, vaccination and the eradication of several once deadly diseases. For this reason, we are today, fortunately, much better prepared to deal with new diseases...

But we are, on the other side of the coin, much less prepared than our ancestors to deal with death... And, in fact, although we know, in theory, that epidemics are cyclical, as history helps us to remember, they are not we are also unprepared to deal with them.

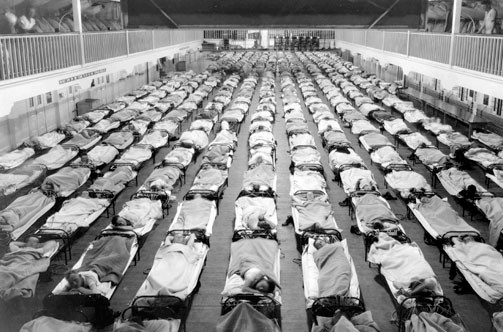

Just as our grandparents and great-grandparents weren't when, at the end of 1918, they had to face one of the deadliest pandemics in history: the pneumonic flu, also known as the Spanish flu, caused by a strain of the virus Influenza a, H1N1 subtype, highly contagious and particularly aggressive, causing pneumonia and responsible for a high mortality, especially in healthy young adults, and not as high as would be expected in risk groups such as the elderly, the chronically ill and children .

During the years 1918 and 1919, it is estimated that pneumonics affected around 500 million people and caused the death of between 50 million and 100 million people worldwide; it added more victims than the Black Death in Europe, more than the First World War (16 million) and probably more than the subsequent Second World War (between 50 and 85 million), and was therefore responsible for the disappearance of some 5% of the world's population at that time.

The origin of this disease is not known for sure, although most scholars argue that it appeared in a US military field, in the state of Kansas, and that it spread from there, across the Atlantic and the Pacific, to other continents.

The rapid spread of the disease was largely facilitated by the movement and subsequent demobilization of the troops of the Great War, which ended in November 1918. Pneumonics developed in three waves: the first between March and April 1918; the second wave broke out in August until the end of that year and was the most virulent and deadly; the third wave occurred early in the following year.

In this scenario, Portugal was no exception. It is estimated that this flu was responsible for the death of 2% of the Portuguese population (about 135.000 people), uncovering the weaknesses of the country's medical care network during the unstable government of Sidónio Pais, at a time when Portugal suffered from adverse effects of participation in the Great War and faced a serious economic, political and social crisis.

The second and most intense wave of pneumonics began in the region of Porto, in Gaia, in mid-August and from there it spread to the rest of the country. It would arrive in the Algarve in early October 1918. And, like the new coronavirus, it was also a very democratic virus, which infected and affected people from all social groups.

Here, the lawyer and poet João Lúcio, who at 38 years of age, would not resist him for “Impressionist and soft Algarve”.

The two municipalities that were initially most affected in the Algarve region were Loulé and São Brás de Alportel, where the intensity and fatality of the pandemic immediately caused some panic among the population, reported by the regional press.

From there, it spread to the neighboring counties of Tavira, Olhão and Faro in the second half of October and before the end of that month, the districts of the windward were also affected, namely Portimão, Lagoa, Lagos and Monchique.

The last affected municipalities seem to have been Albufeira, Aljezur and Alcoutim, where the mortality rate was highest in November; however, no municipality in the Algarve, be it from the leeward or the windward side, escaped the pandemic outbreak, which had very disastrous consequences for the population.

In a telegram addressed by the then Civil Governor of Faro the President of the Republic was asked to protect the Algarve against an absolutely dire scenario, stating that the “epidemic is sweeping away entire villages, with cemeteries already completely full, with burials being carried out in shallow graves.

There is a lack of medicines, rice, sugar, candles, oil, pasta, butter, potatoes, and there has been no bread for three days”. This scenario was not exclusive to the Algarve region and the central government was then forced to take measures to combat the pandemic… however, not as drastic as they actually should have been, in order to contain the disease. The then Director General of Health, Ricardo Jorge, believed that since the flu is caused by a virus, only a vaccine could solve the problem, so he considered that traditional measures such as isolation would be ineffective.

For this reason, he even defended that social life and distractions should continue in order not to increase isolation and panic among the population.

However, the high contagion eventually led to the closing of schools and universities, public services, and fairs and pilgrimages were banned.

Measures were taken, in conjunction with the local authorities, which included informing the population of adequate prophylactic measures in the fight against influenza, ensuring the sufficient presence of doctors in all districts to assist in cases of illness, and providing better care in pharmacies, as well as the availability of medicines. In addition, the Portuguese State undertook to financially help the health delegations in the districts to help the populations affected by the pandemic. Still, too late.

The State's response did not follow the rapid spread of the flu outbreak, revealing not only the difficulties of communication between the center and the periphery, but also the fragile structures of support and assistance in health in Portugal.

The last three months of 1918 corresponded to a scenario of chaos and panic throughout the country, with disastrous consequences not only demographic, but also economic and social, in an already very complicated situation.

They helped to highlight the weaknesses in the response of the State and of the various authorities, weaknesses which, after the events, are always so easy to point out, but which, in the final analysis, are above all the result of decisions that are very difficult to make to those responsible to act in an atypical period of crisis and pandemic outbreak.

However, I did not want to end this reflection by highlighting the weaknesses of the time, which may well be the ones now, but rather to end it by recalling how, in the face of such a difficult and tragic situation of loss of so many lives, it was unleashed in the Algarve, like all over the country, civic movements of social solidarity and mutual help, which started with anonymous citizens, associations, local support commissions, the bishop and parish priests, among others, who contributed as much as possible with money, food and other foodstuffs, or helping the authorities in the treatment and prevention of the disease, or even in the transmission of information and in the support and comfort of those most in need.

For this, it is enough to remember the donations of the insurance company “A Latina” to the municipalities of Silves, Portimão and Faro; or the action of the industrialist João António Júdice Fialho who, during the epidemic, maintained an organized system of support services during the disease for his employees and their families; or even the support of the Ladies of Charity Association of Faro in fundraising for the most affected families – this is just to highlight a few examples, among the many others that occurred at the time.

Catastrophic and dramatic situations, which threaten our lives and the lives of those close to us, are also situations that tend to bring out our empathy and compassion for the drama of others.

These are times when we feel compelled to help others. We can, at this moment, find some comfort in our history, remembering that, in 1918, our grandparents and great-grandparents were subject to very adverse circumstances, perhaps much more painful than ours, and that they were, even so, able to overcome them ; they dealt closely with the disease and the loss of family and friends, and still found courage and strength to provide assistance to those most in need.

We can and must, at this difficult time, make every effort to do our part in the fight against Covid-19... even if it seems to us that our part is small and even if it only corresponds to staying in the privacy of our home, protecting it not only ourselves, but others as well. If we all do our part, all the parts, which may even look small, together become big and become strong!

At this moment, we must remain united around the same common objective: to overcome, in the best possible way and with the least possible damage, this pandemic. And it will be!

Author: Andreia Fidalgo is a Doctoral Scholar at the Foundation for Science and Technology and Invited Assistant at the University of Algarve

Note: Article originally published in blog «Place to the South» and here republished as part of the partnership with the Sul Informação

Comments