Syria's civil war is still the order of the day, however, just over 180 years ago it was Portugal that was in a similar situation.

Syria's civil war is still the order of the day, however, just over 180 years ago it was Portugal that was in a similar situation.

In fact, the first half of the 1851th century was dramatic for the Portuguese. From the French Invasions to the Regeneration in 1832, the country went through revolts and counter-revolts, such as the civil war, from 1834 to 1840, and then Maria da Fonte and Patuleia, in the 1834s. In the Algarve, between 1842 and XNUMX, there was also the Guerrilha de Remexido to sow panic and terror in the region.

The Loulé massacre, on July 24, 1833, was part of the civil war, which pitted the supporters of D. Miguel, convinced of the absolutist ideals, to those of D. Pedro, who defended liberalism and with it the separation of powers (judicial, executive and deliberative), based on a constitution.

Both were brothers, sons of D. João VI and D. Carlota Joaquina. Upon the return of the royal family from Brazil, where they retired in 1807 following the French Invasions, D. Pedro, the eldest son, remained in that kingdom, declaring his independence in 1822.

It is recalled that the royal family was summoned to return to Portugal following the Liberal Revolution, which broke out in Porto on August 24, 1820. Uprising that, unlike Portimão, Faro or Castro Marim, was frowned upon in Loulé.

The Chamber and other authorities of the town, meeting on September 6, 1820, not only condemned the movement, but also called the city of Porto, which was “uprised by punishment from Heaven”, illegitimate, and considered the “government established in that disgraced city”.

The emancipation of Brazil promoted by D. Pedro, who soon called himself emperor, was stigmatized by the majority of the Portuguese, who saw the “crown jewel” disappear.

On the other hand, D. Miguel had entered, since 1823, following Vilafrancada, on a collision course with D. João VI, for defending the absolute regime, in opposition to the constitutional one, being exiled in Vienna from Austria in 1824, after new attempted coup d'etat (Abrilada).

With the death of D. João VI in 1826, was the dispute open about who should occupy the throne: the first-born D. Pedro, emperor of Brazil, who had promoted the split in the kingdom, or D. Miguel, the exile?

D. João VI had indicated D. Pedro as his successor, who abdicated in favor of his daughter, who was to marry his uncle D. Miguel, who would remain regent until his majority.

D. Pedro also granted the Constitutional Charter, given that the 1822 Constitution had been suspended since Vilafrancada. D. Miguel agreed with the plan drawn up by his brother, however, shortly after returning to Portugal in 1828, he called himself absolute king, corresponding to the wishes of a considerable number of Portuguese, while many others emigrated en masse to Europe, escaping the summary executions and the Miguelista terror (thousands of people were arrested and deported).

In this sequence, D. Pedro abdicates the emperor of Brazil in his son D. Pedro II and leaves for Europe in 1831, to try to restore the throne of Portugal to his daughter, usurped by D. Miguel.

Established in the Azores, D. Pedro will head north, occupying the city of Porto with an army of about 8 men, supported by 000 ships.

The siege of Porto, as it would become known, lasts for a year, with no advantages for any belligerent.

With renewed support from Great Britain, the liberals chose to send, in a squadron, an expedition to the Algarve, with 2 men led by the Duke of Terceira. Men who would later head for the capital of the kingdom, proclaiming there D. Maria as the legitimate queen of Portugal.

The disembarkation took place in the vicinity of Altura on June 24, 1833, and, in the following days, liberalism was acclaimed in the region with relative ease, and the new civil and military authorities were appointed.

The absolutist troops reverted to a prudent expectation, not interfering in liberal movements. On the 13th of July, the Duke of Terceira left the region, by land, towards Lisbon.

With the departure of the liberal army, the absolutist forces concentrated in Almodôvar, where they were divided by the absolutist leaders Remexido and Camacho, whose objective was to set in motion the Miguelista counteroffensive.

Thus, the first should acclaim King D. Miguel in all locations in the Barlavento Algarve, while Camacho had the same mission in the Sotavento.

On the 24th of July, the Duke of Terceira triumphantly entered Lisbon. Liberals owned not only Porto, but, from now on, also the capital.

On that same day Camacho, or rather Major André Camacho Jorge Barbosa, invested in Loulé, who, in opposition, fell to the Miguelistas, “under the rash of an absolutely inadmissible, barbaric and inhuman bloodbath”, in the words of Professor Vilhena Mosque.

Remexido was also advancing on Albufeira in those same days, however, if it is possible to describe in detail what happened here, based on the “Memory of the Disastrous Events of Albufeira”, the same does not happen with Loulé. Even so, supported by Ataíde Oliveira's “Monografia de Loulé”, dated 1905, we will try to revisit that fateful day.

Camacho had concentrated on the Algarve mountains, where he had easily recruited men to his guerrilla. The successful recruitment seems to have been related to the repulsion of the people of those places to the disturbances provoked by some Louléans and French soldiers, days before, in the church of Salir.

When they arrived at the village, they not only caused some confusion, but they invaded the church, where they simulated a fight with the sacred images, beheading them, pouring and stepping on the pyx's hosts.

Such an attitude revolted the Salirians, who will have pursued the transgressors, but without capturing them. News of the vexing event quickly spread to the surrounding inhabitants, who, insulted by their convictions, swore revenge.

The enlistment in Camacho's guerrillas provided the desired retaliation. Despite the fact that news emerged in Loulé of the composition of a horde in the Quinta do Freixo region, which intended to invade the town, it was neglected.

On the night of July 23, about 3 guerrillas arrived in Loulé. The major's plan was to surround the entire village in the dark, so that the next morning, when the offensive took place, no one would escape.

Still, an accidental shot will have allowed a prudent Louléan to escape into Faro, at a time when the cord was still open.

About the attack, Ataíde Oliveira wrote:

“When the villa awoke from its sleep of indolence, it found itself surrounded. The catastrophe followed. Then some guerrillas on the outside with some compadres inside began the assault. There was a small shooting. They kissed the ground of death, in combat and murdered, thirty French soldiers; and the others withdrew to Faro. Then the killing began; and it was seen that the guerrillas on the outside were bad, the guerrillas on the inside were no less infamous. The rich and creditor compadre was murdered by the debtor compadre. Murder was being murdered at the same time as the assassins were cheering on the holy religion.”

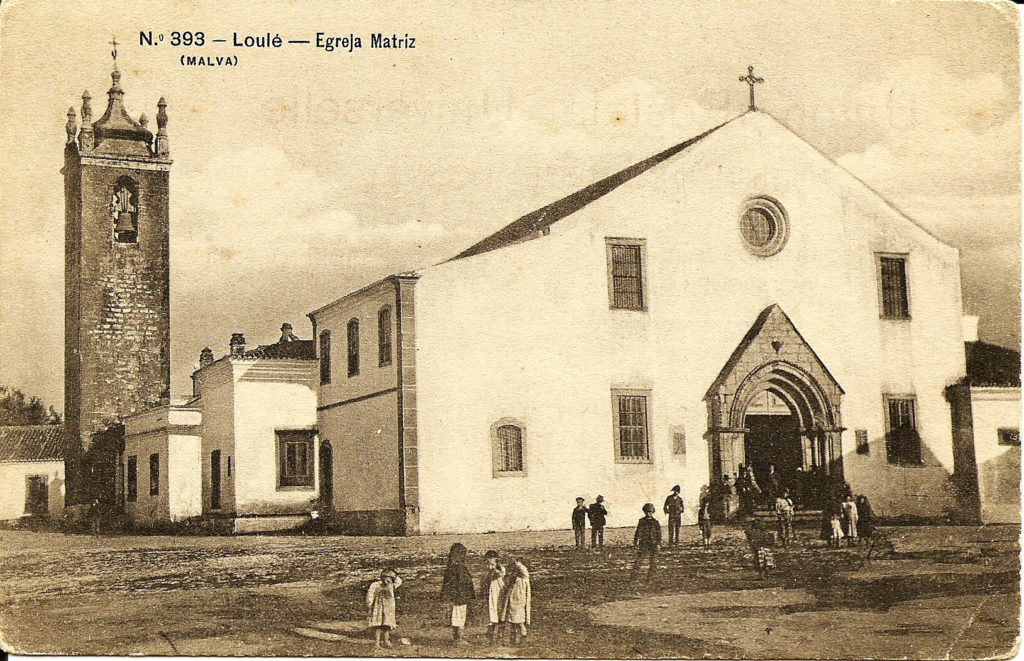

The slaughter took place in the streets of Corredoura (now Eng. Duarte Pacheco), Santo António (Miguel Bombarda), and Barbacã, in front of Bicas Novas (large Dr. Bernardo Lopes), next to the sacristy, but also in the victims' houses, where the guerrillas entered and searched everything, or in places where they had sought refuge, such as backyards or even in a pigsty.

Shot, with a stick or a stick, tortured and burned, no means to achieve the ends were considered. The exact number of dead varies depending on the source.

Ataíde Oliveira mentions 30 French soldiers, and then enumerates, based on a process instructed in 1835 by the Public Ministry, 32 more victims.

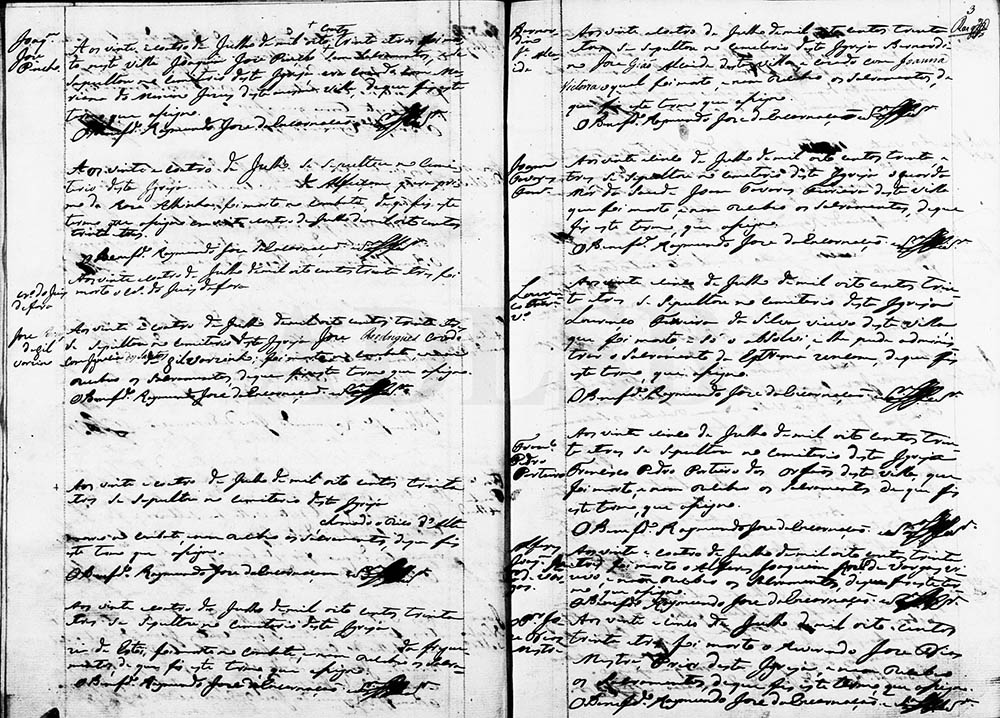

In the Book of Deaths of the parish of Loulé, on the 24th and 25th of July, 28 dead were recorded, with the note of having lost their lives “in combat”.

None of these are French and although there are four unidentified, because the parish priest is ignorant, the available data indicate that they are Portuguese.

Among others, the deaths of the judge of Fora, his clerk, the prior of Loulé, the mayor, a captain, an ensign or even a Spaniard residing in the village are registered.

The violence subsided in the following days, but did not cease, with eight more seats, of people murdered until 5 August, including a woman, dead, in the street and thrown into a dunghill.

Three years later, in 1836, the Loulé Council estimated the total number of victims at 49. This number would certainly include some individuals taken under the pretext of trial to the outskirts of the village, where they were shot and buried without any record, a very common practice at the time.

Proclaimed D. Miguel among the Louléans, Major Camacho appointed and sworn in the new council of the Loulé Chamber, three days later, on the 27th of July 1833, now faithful to this monarch. In the region, in the following months, only Faro, Olhão and Lagos did not fall into the hands of the absolutists.

With the definitive victory of Liberalism, expressed in the Convention of Évora Monte, on May 24, 1834, various demands for compensation were instituted all over the country, by the victims of the “usurpation”.

In Loulé, around 30 cases were filed relating to the damage that the petitioners claimed to have suffered during the assault on the town on 24 July 1833.

The entry into the houses was almost always accompanied by the complete destruction of its contents. Scholars, owners or merchants were usually the victims, either for their liberal connotation, or in the case of merchants for their deadbeat customers.

The captain and trader José Rafael Pinto was one of the applicants, presenting his relationship divided into four main topics: “Genders”; "Furniture"; “Silver and Gold”; and “Giblets”.

In the “Genres” category, he entered varying amounts of cereals, but also 20 arrobas of pork, two tuna barrels, wine, brandy, vinegar, straw, carob, almonds, figs, fresh fruit and even lettuce.

In “Furniture”, he listed chairs, canapés (with the mention that he had acquired them in Lisbon and Porto), tables, chests of drawers, trays, tender boards, beds, chests, an oratory, locks, doors, etc.

In “Pratas e Ouro”, he inventoried, for example, several pieces in silver of a cutlery, glitters, a palm, thimbles, an object with real arms, already in gold, palm earrings with diamonds, a cord, rings and pins and, perhaps most surprising, a medal from the “usurper” D. Miguel.

Finally, in “Miudezas”, there were pans, men's and women's sun hats, baskets, esparto nets, 16 Moorish hens and eight dozen straightening combs, among other objects.

To all this, José Rafael Pinto added 300$000 reis of the profits he should have earned with his business, during the year he was emigrated to Faro.

It is possible that José Pinto is the individual who fled Loulé on the night of 23 July. It is certain that he ended their relationship asking for 4 872$870 reis in compensation, a fortune for the time.

However, as the old popular saying goes, “no mistake in asking”, was certainly the case. But if José Rafael Pinto could assert his rights, about fifty paid with their lives for the ideals they defended, either simply because they were at the wrong time and place, or even for mere settlement of accounts between neighbors and “ friends".

The Loulé massacre, carried out by Camacho, and the Albufeira slaughter, commanded by Remexido, constituted the height of the terror of the civil war in the Algarve.

As for the leaders, Major Camacho escaped to Brazil in September 1834, while Remexido remained in the region, being shot in Faro, after forming a new guerrilla, between 1836 and 1838.

Camacho, in turn, would return, years later, to Portugal, coming to enjoy a normal life. If in fact he was amnesty for crimes committed during the civil war, there was no lack of examples, in the years immediately following the end of this one, in which this pardon was not respected. The evasion saved his life, so that the Louléans were not killed in the attack he carried out on July 24, 1833.

So in Portugal, today in Syria, 184 years later, “developed” humanity continues to impose ideas and ideals in cruel and bloody civil wars.

To know more:

– Francisco Xavier de Ataíde Oliveira, Monograph of the Municipality of Loulé, 4th edition, Algarve em Foco, 1998.

– José Carlos Vilhena Mesquita, “The Remexido and Miguelista Resistance in the Algarve”, Al-'ulià – Magazine of the Municipal Archive of Loulé, n.º13, 2009.

Author Aurélio Nuno Cabrita, environmental engineer and researcher of local and regional history, regular collaborator of the Sul Informação

Comments